There aren’t many Kolkatans who would know that during the Second World War, their beloved City of Joy was in the thick of the action. Only a handful of octagenarians belonging to the generation that lived through the war would recount the frequent bombings near the city docks or a slit-trench near Ramananda Chatterjee Street. Towards the end of World War II, the city had indeed found itself on the enemy forces’ radars. The War had finally touched Calcutta and how!

Calcutta and World War II

Although India was not directly involved in the Second World War, it was a confederate of the Western allies of the British. And Calcutta, too, came to assume a pivotal role as the war progressed. David Lockwood, in his book Calcutta under Fire writes, “Calcutta served as an industrial centre, a port and a transit point for troops moving up to fight the Japanese in Malaya and then in Burma. It was a city of considerable strategic importance to the allies.” It was, thus, a matter of time before the city would be sucked into the all-consuming whirlpool of power politics.

On February 15, 1942, Singapore fell and on March 8, 1942, Myanmar (Burma) met the same fate. This led to the blocking of Burma Road, and Calcutta became a major spot in the supply chain of allied forces. Soon, US planes were flying from Asansol Airstrip and the Panagarh military airbase. By October 1943, the city would be witnessing the laying of a pipeline from the port of Calcutta to Tinsukia in Assam, that later extended to Himalayan regions.

The first attack on the City of Joy

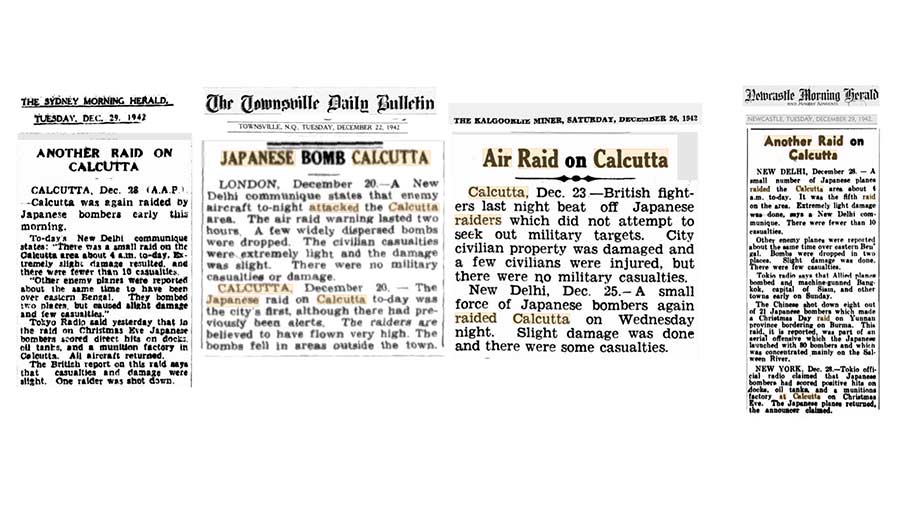

International newspapers’ coverage of the air raids on Calcutta by Japanese forces

It was on the night of December 20, 1942, that the first officially recorded attack by Japanese bombers took place. Bombs dropped all over the city, and records would show that Dalhousie Square, Mangoe lane and Hatibagan were some of the areas that were directly affected by the attack.

There were repeated air attacks between December 20 and 28, 1942. One of the bombs slightly damaged an oil plant in Budge Budge. There was no military damage, but a few civilians lost their lives.

By now, the earlier rumours that since Netaji Subash Bose was on their side, the Japanese would not attack Calcutta were falling apart. The Japanese had fooled the allies and attacked an almost defenceless city, solely to paralyse the docks and the supply route through Calcutta port. People had started to lose confidence in their British rulers.

The fightback

Soon, the Royal Air Force had begun its fightback. When the Japanese ‘Sallys’ — a code name for the Mitsubishi Ki-21 bombers — attacked Calcutta for the first time, two Hurricane squadrons (nos. 146 and 17) took over the air defence of the city. Wing Commander John Anthony O’Neill intercepted three Japanese bombers on the night of December 23 and damaged one of them. He bettered his performance the next night by intercepting 10 ‘Sallys’ and destroying one of them.

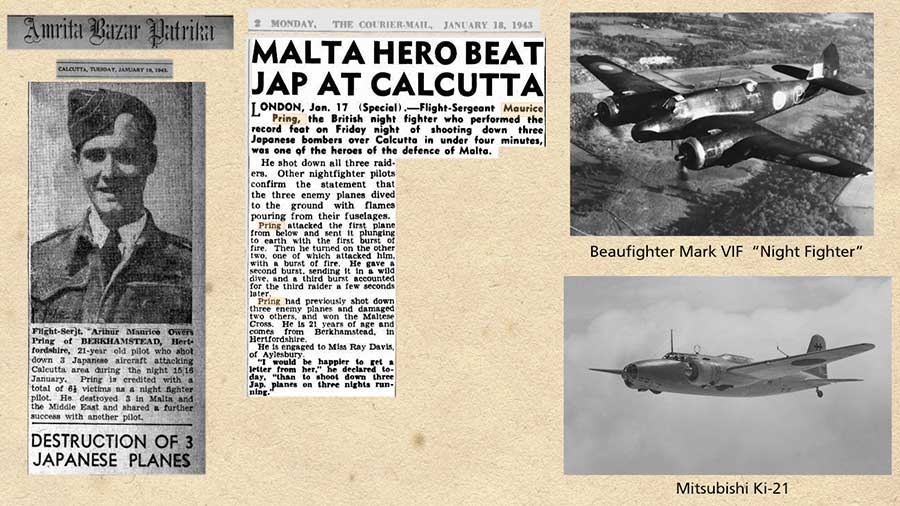

In this phase of retaliation against the Japanese bombers, a 21-year-old flight sergeant, Arthur Maurice Owers Pring, also accomplished the heroic feat of annihilating three ‘Sallys’ in a matter of minutes in January 1943. With a much-needed boost of morale, Flight Officer Charles Crombie soon had also shot down one more enemy bomber, while severely damaging another.

Newspaper reports covering the news of Pring’s extraordinary feats and the Japanese plane models he shot down

Faced with such successive and successful attacks by the Royal Air Force, the Japanese refrained from attacking Calcutta for almost a year.

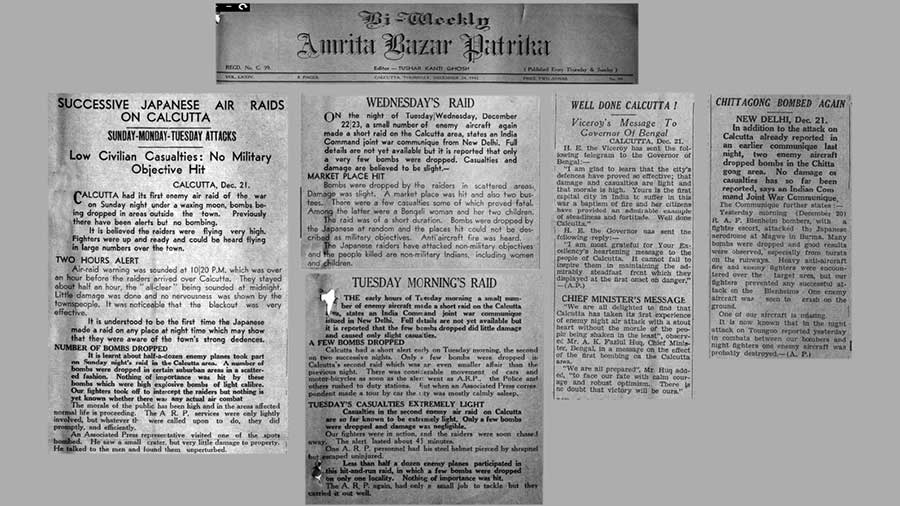

In spite of the valiant defence that the British carried out throughout 1943, by the end of the year, Calcutta was practically a defenceless city with only a few Hurricanes to defend it. Spitfires and Baeufighters — both fighter aircrafts relied on heavily by the Royal Air Force — were redirected towards Chittagong. There were innumerable casualties too. On December 7, 1943, a report in the Amrita Bazar Patrika informed the public that the result of the attacks was 500 civilian casualties of which over a third were fatal. Yugantar echoed their report, as did American newspapers like Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and The New York Times.

Reports of Japanese air raids published in the Amrita Bazar Patrika

Soon, there were other problems to tend to. Calcutta was grappling with widespread famine by December 1943, thanks to the ‘denial policy’ of the British and Churchill’s reluctance of importing food grain. The Japan attacks had started to become a faded memory.

Was there a spy?

Kolkata Port trust security adviser Gautam Chakraborti, who is a well-known heritage enthusiast, claims that an enemy espionage network must have been active in the city during the Japanese attacks. “Otherwise, in December 1943, how will they know the exact moment to strike and that too in broad daylight?” asks Chakraborti. There is also a popular story about a possible spy in the Wireless Telegraphy department of Fort William who used to relay sensitive information to the enemies.

Shops and buildings on Bentinck Street, one of the sites bombed by the Japanese, today Amitabha Gupta

A walking tour of the bombed sites

Heritage enthusiast and blogger Subhadip Mukherjee has always been curious about the exact locations, especially those in and around B.B.D. Bagh, where the city was bombed during World War II. Equipped with a five-minute-long video clipping from a British Movietone newsreel, Mukherjee embarked on a quest to locate the spots, accompanied by friend Shaikh Sohail. It was the latter who realised that a visit to all these spots could make for an excellent walking tour for history enthusiasts.

According to the duo, the first bombing spot that visitors can look for is at the entrance of Mangoe lane from R.N. Mukherjee road. Sohail thinks that the actual was probably the Central Telegraph Office located nearby, as any damage to the site would mean a successful termination of all communication channels. Mukherjee pointed out that it seems from the video that the telegraph office did suffer some damage.

The Central Telegraph Office was probably the target of the first bombing Amitabha Gupta

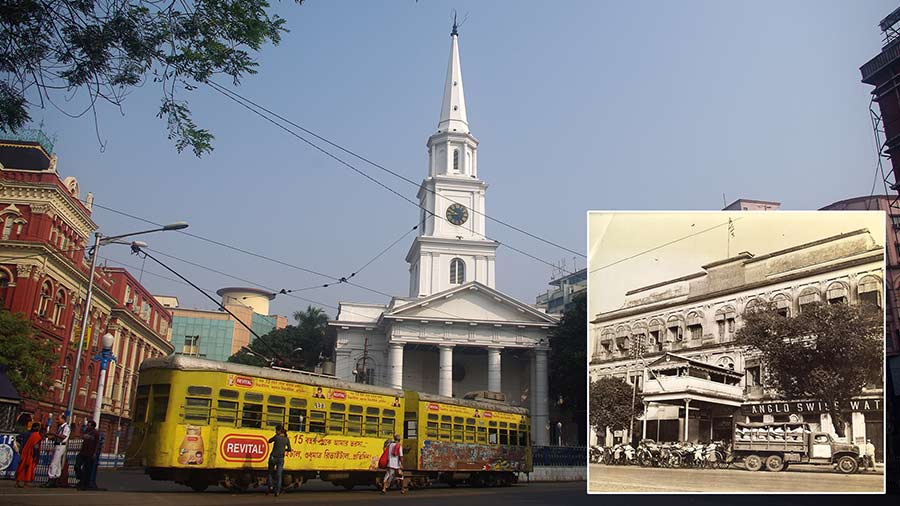

The second bombed site is near St. Andrew’s Kirk. Sohail thinks that the target might have been the American Red Cross Burra Club which stands very close to the location. This was a leave centre for American GIs and recreation spot for all enlisted men.

St. Andrew’s Kirk and (inset) the American Red Cross Burra Club Amitabha Gupta

On B.B. Ganguly Street is the third spot, located near a gun shop. A signboard seen in Mukherjee’s video helps locate this place. This site is very close to Lalbazar Police Headquarters. There were at least two bombs dropped on Bentinck Street.

During the war, the GPO and the Writers’ Building were prime targets for the Japanese because of the crucial role they played at the time. These two locations were pivotal in war correspondence and were also tasked with the responsibility of keeping a check on war rumours.

The GPO and the Writers’ Building, owing to their pivotal role in war correspondence, were prime targets for the Japanese Amitabha Gupta

Having watched the video footage closely, Mukherjee is of the opinion that, during the attacks, a bomb had landed in Fairlie Place, which is just 200 metres from Writer’s Building. St. John’s Church, too, suffered damages to its structure when a bomb exploded inside the church grounds. Calcutta was lucky that the other major landmarks in the city, like the Howrah Bridge, were spared by the Japanese forces.

St. John’s Church, too, had suffered damages during the air raids Amitabha Gupta

Those interested in taking a walking tour of the spots bombed in the city during the Second World War can do so with the help of Break Free Trails. Keep an eye on Break Free Trails’ pages on Facebook and Instagram.