Continued from here.

When you drive from south Kolkata, descend the Chowringhee flyover and come to an enforced pause near the four-crossing, the structure you instinctively turn to will be Metropolitan Building at the one o’clock position – the golden dome, giant clock, arched balconies and façade extension that streaks into SN Banerjee Road at one end and down Chowringhee at the other.

The Metropolitan Building is a mood-setter. It speaks of grandness and yet of style. It reflects architecture and yet aura. It is probably the only structure with as strategic a location in that part of the city. It is located at the convergence of the city’s arterial Chowringhee and SN Banerjee Road, drawing thousands of hourly footfalls. The size of the road it faces is probably the widest in Calcutta (which means its competition comes only from the GPO and the road that passes beside). One can stand diagonally across Metropolitan Building – facing the clock – and see the two equidistant arms of the building merging into the central edge, an outstanding 0.5 composition on the smartphone (which also explains why the building has inspired a genre of painted work visualised from the same position). The merging of the Metro rail with the other transportation modes makes this location possibly the most accessed in Calcutta.

The old Whiteaway, Laidlaw & Company building on Chowringhee – this was no ordinary outlet; it was the Oriental Harrods Wikimedia Commons

The Metropolitan Building was created by the departmental store Whiteway, Laidlaw & Company. The department store was nicknamed ‘Right-away & Paid-for’ because of its prudence-first approach: no credit. The store was positioned as a colonial emporium that eventually branched into outlets in Bombay, Madras, Lahore, Simla, Colombo, Rangoon, Singapore and Shanghai. This then was no ordinary outlet; it was the Oriental Harrods; it was the head office with retail cross-border tributaries that turned to it for retail direction, pricing and positioning.

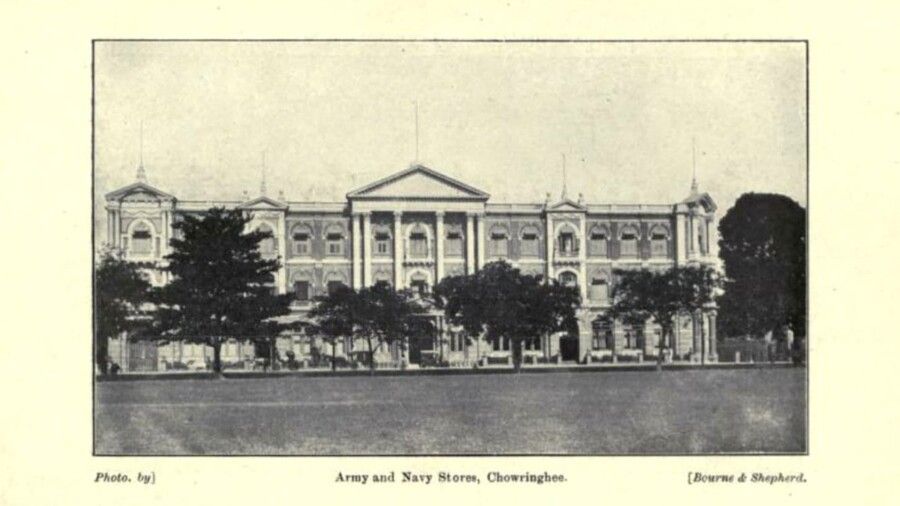

At the heart of this enterprise was the architecture. The ‘wedding-cake’ structure was curated by Mackintosh Burn & Co. – designed not only to facilitate, but also to attract. A Britisher of the time (Norman Watney) recalled: ‘Whiteway's had acquired the distinction of being solely for those with small purses and had a large clientele of junior officers. Others in a more senior position used to go down the road about a quarter of a mile away to the Army & Navy Stores.’

The Army and Navy Stores opened with fanfare in 1901 ‘Recollections of Calcutta For Over Half A Century’, Montague Massey/archive.org

It is unthinkable that modern-day stakeholders would have permitted a retail company to construct a building, however low the prevailing interest rate or however high the liquidity. The departmental store would have had to pay no rent; the residential wing of the structure (Victoria Chambers on the second and third floor) would have brought in predictable liquidity (fancy running a world-class departmental store on the strength of 20 apartments). The structure represented a new ideal for Kolkata lifestyles – the coming together of high-end retail, residential living, extensive green in front, anytime accessibility and just across where lived the man who stewarded the British Empire (I can almost imagine that the design of the structure passed a few reviews to appraise whether its style, scope and scale matched the desired colonial aura).

One of the clock towers Mudar Patherya

The form attracted a corresponding following. The initial residential mix comprised names like Copping, Hamilton Jewellers, Ewing, Calcutta Tramways (for its senior management), Depenning, Balmer Lawrie, Tea Board and Da Silvas, among others. The standards fell into place as a logical extension: there were different entrances for different classes; the back-home staff was not permitted escalator use; the bannisters were polished brown; the carpet on the staircases were held in place by polished parallel end-to-end rods; the brass doorknobs would be periodically polished; there was possibly a café under one of the domes (inferenced by the fact that the architects provided for a small rest room below the dome); the seven entrances to the building spoke of an opulence of vision and neighbourhood safety; the Italian stained glass on the first floor cast a multi-coloured shadow influenced by the watch.

Esplanade from the terrace of the Metropolitan Building Mudar Patherya

This differentiated lifestyle extended into the interiors. The ceiling was – and is – 20 feet high; apartments are 2,000sq ft-plus (some 3,000-plus); each apartment opens into an ante-room that leads into a drawing room; the wood is Burma teak; the chequered floor was drawn from the quarries of Italy; each apartment is coupled with a section for the domestic staff. In ancient times, if a sahib in the quiet of the night said ‘Boy!’ at a high decibel, he could be assured that someone 30 feet away would be springing out of bed, hurriedly buttoning his shirt and leaping to present himself at the bedroom door with a soft knock and ‘Jee saheb’. The domestic staff was multi-generational (‘Hamara baba ka baba bhi yahaan kaam kiya hai’). And during various time pockets of the day, one could always sip the best of Assam and Darjeeling in the verandah and watch life gently stream by.

The ceiling was – and is – 20 feet high; apartments are 2,000sq ft-plus (some 3,000-plus) Mudar Patherya

Metropolitan Building was not a structure; it was an experience.

Then the world changed. The British vacated. The building ownership Indianised (Metropolitan Life Insurance Co.). Victoria Chambers became Satchindananda Chambers. Traffic increased. Trams disappeared. The tram depot turned into a ‘warehouse’. Metro (cinema) wound down. Protest rallies increased. Bourne & Shepherd burned. Hawkers overran the pavements. Cacophony triumphed. Dust settled. The Statesman repurposed. Lahore Restaurant shuttered. Anarkali Restaurant exited. Café de Monico faded. Saqi Bar switched the lights off.

Metropolitan Building evolved. Residents moved out. The landlord (now Life Insurance Corporation following its acquisition of Metropolitan Insurance) regulated new tenancies. Familiar faces declined. Homes remained empty. Offices increased.

The old Metro cinema sign Mudar Patherya

If you speak to the old timers, they will speak of Metropolitan Building with a wistfulness on the passing away of a family member. They speak of resident Shubho Tagore who floated bard-like in his robe. They speak of a flamboyant AN John who wore coloured suits and matching shoes. They speak of film actors (Naseeruddin Shah, Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil) turning up to party at the residence of Shyamanand Jalan after a successful premiere next door. They speak of neighbours who smiled and said ‘Good morning’ when they passed. They speak of the vast stained glass sheet that has long since disappeared (‘One late night there was a large dhadaam-jaisa crash. I trembled that the building was possibly about to collapse. The framework holding the stained glass had given way and all we now have left is the place where it once stood – nothing else’).

The extensive terrace Mudar Patherya

There is still some jaan left. The present-day owner may not be visibly enhancing value, but it is defensively protecting, which is still a good thing when you consider the kismet of some north Calcutta properties. I would like to engage with the LIC estate manager, if only to explore the possibility of the extensive terrace being turned into an effective cultural platform (KALAM literary meet if I have to cast an idea in the open), whether one can use its sheer openness to curate winter al-fresco and whether – the laziest of ideas – we can park solar panels and use the generated electricity to uplight the façade of this magnificent structure.

The best could yet be.