Continued from here

Gopal Bhavan is the most paradoxical structure on Chittaranjan Avenue. When you drive northwards from the Mahatma Gandhi Road intersection you arrive at where Chittaranjan Avenue crosses Muktaram Babu Street. The paradox looms into your consciousness when you move closer — a vertical glass facade of an unusually large building on the left.

My first dismissive response: “Someone must have built a mall-like structure in the last decade.” If you drive just a few metres beyond this architecturally mismatched creation, you sense that something is different. The next building appears to be an architectural extension — same vertical and horizontal dimension. That is when it becomes evident that this building — the 1926 vintage Gopal Bhavan — comprised twins conjoined from birth. Decades later, someone decided that one half of this magnificent structure would be glassed from the ground upwards and concealed from public view and the other half would continue to be presented to the world the way it has been originally designed; the heritage committee remained unbothered.

The result has been the most blatant, desensitised and uncensored architectural assault on a Kolkata facade in recent memory.

An old photograph of Gopal Bhavan, which was built in 1926

The assault is ironic because Gopal Bhavan is arguably the handsomest structure on one of the handsomest roads of the city — for its imposing Indo-Greek architectural convergence. I would suggest that you stand alongside the road divider with Ram Mandir behind you, and look up. Gopal Bhavan was not designed to soothe, it was curated to impose. If the structure could speak, it would be in the bass of a KBC quiz master; if the structure could strike, its echo would announce a durbar entry.

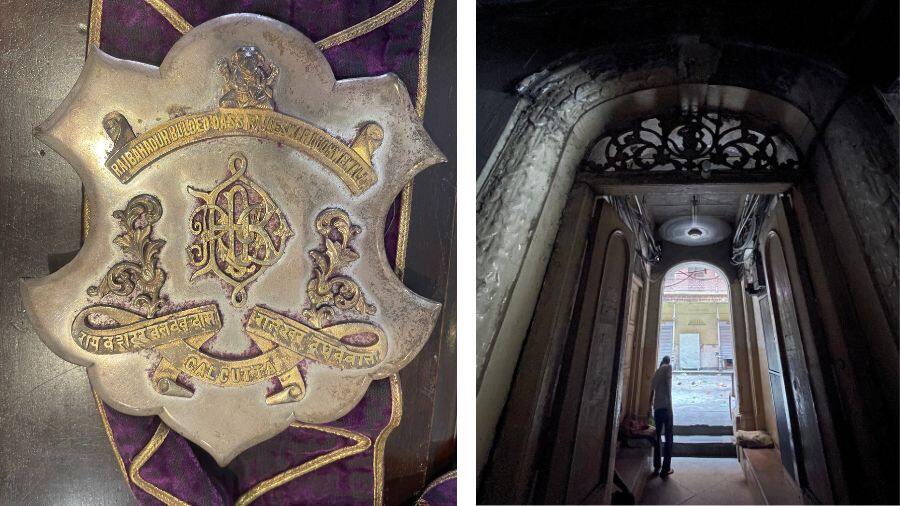

The imposing architecture has a backstory. Rameshwar Nathany was a speculator and investor from the 1920s with large stakes in jute companies. His investments worked well. A small part of that went into the construction of the family estate, commercial establishment and store house (Gopal Bhavan), and the other half of this property was rented. The Nathanys were people of means. They were among anonymous founder-donors of Doon School, constructed and managed 14 dharamshalas across India, owned a stake in Sanmarg and ‘ran a CSR book’ well before the term had been conceived.

Gopal Bhavan was the office building and home of the Nathanys

The stories of this Nathany ancestor are legend. One of them goes like this: the to-be tycoon Ramkrishna Dalmia worked in the Nathany broking firm as a munim. The seth conveyed verbally a buy order for 5,000 shares of a specific company. Dalmia mis-heard; he brought 10 times the quantity. By evening the sauda (transaction) was scrutinised and the error located. The prices had moved and the firm was sitting on an unwitting profit. The transaction was immediately squared (out of relief). What happened thereafter was unexpected: presumably, the young Dalmia was summoned with a word of caution to be more careful in taking verbal saudas; thereafter, he was handed the entire trading gain — ‘thaaro saudo, thaaro faaydo’ (your deal, your profit). Through this stroke of unintended error and unusual generosity was created the seed capital that possibly transformed a clerk into a capitalist who would one day germinate one of India’s largest business empires.

There is another Nathany story that has become legend. In the early ’40s and war-time India, the patriarch went long on silver. The quantum was large; this single man had single-handedly created a bull market in this precious metal. At first, local traders took notice and thereafter, the word spread to the other markets that ‘Calcutta ka lay-oo hai’ (Calcutta is buying). The word went international that the demand for this metal was coming from a corner of the commercial capital of India, and was it something that this trader knew that the others had missed. In the London bullion markets, the whisper was that a milkman (originating from the fact that the alternative Nathany family surname was Doodhewala) was betting unprecedented cash on silver.

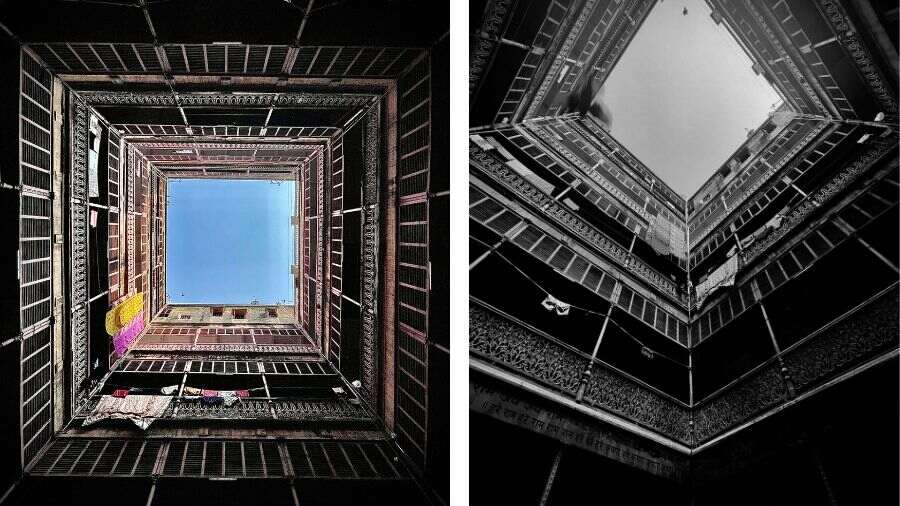

The heart of Gopal Bhavan was its courtyard-centric architecture

The bull ran fatigued. Those who held silver positions booked profits. The Nathany firepower was consumed, the price plateaued and then declined. Initially, the Nathany family took delivery of all it could with its savings (or debt); the Gopal Bhavan chowk was stacked pillar to pillar with silver. It is only when fresh purchases could not be sustained that it appeared that the game was over. Whatever could not be physically purchased and inventorised was progressively squared, and the loss difference was paid. The more silver declined, the larger the margin difference and the more the physical inventory disinvested to plug the difference.

This turned into the biggest crisis that the Nathanys had encountered. Well-wishers felt that the most plausible thing to do in the circumstances would be the ‘haath oopar’ face-saver — declare bankruptcy, settle the loss at an amount considerably lower than what needed to be paid, and save some family gunpowder for better days. The story goes that the old man asked for some time, climbed to the mandir, communed with his Maker (“Bihariji ke bharose”), emerged and told the family that the firm would pay down to the last paise and clear its name on the exchange. Given the vastness of the pay-in, one of the banks remained open across seven days to complete the cash transaction. The only concession that the larger family extracted from the patriarch was a written statement of purpose in the vernacular: “No more speculation.”

The Ganesh idol on the pediment

Gopal Bhavan represents a different time. No brick was used in the construction; Italian marble was used in the chowk; there were no toilets attached to homes but were shared. The 500-sq-ft family temple was on the uppermost storey; the ground floor comprised the gaddi (business place); the first floor housed the store room and staff residence; the second and third floors were allocated to families (30 members). A Ganesh idol was fitted into the pediment facing eastwards so that whoever travelled northwards from Harrison Road (Mahatma Gandhi Road) would first do pronaam to the left to the top of Gopal Bhavan and pronaam towards the right (Ram Mandir).

The heart of Gopal Bhavan was its courtyard-centric architecture. In a number of courtyard-designed homes, the chowk evolved into a collective bin, but not at Gopal Bhavan. The rule was that if anyone littered, he or she would be ‘punished’ by going all the way down to remove the thrown away article. If anyone spilled, the compensation would be ‘pota’.

No bricks were used to build this building

There were other Gopal Bhavan attributes that have become anachronisms. The word ‘family’ included immediate relatives — doors of the various families would be generally open until one was ready for bed and homes would be perpetually porous. A heap of slippers outside a door across the verandah corridor indicated where the family children were temporarily aggregating; intra-family business disagreements were resolved by the grandmothers who grouped together, almost inducing the family temperature to normalise. Conversations were often across different storeys overlooking the chowk, when the women stood outside their doors for a few minutes, exchanged sentences, walked inside to address their cooking, emerged minutes later and picked the conversation up where it had been left.

Then one day the idyll ended. Families grew larger. Space per person declined. Unattached toilets became inconvenient. Car parking became an issue. Road upheaval following Metro Rail enhanced ambient dust. Maintenance costs spiralled.

Gopal Bhavan was sold. The mandir’s idols were distributed. The family scattered. Most never returned. The basement tijori (safe) could not be hauled and was left behind.

Gopal Bhavan’s end game transpired after the last Nathany moved out

Gopal Bhavan’s end game transpired after the last Nathany moved out. Well after they had sold the physical did they realise that the emotional had never been vacated. The memories held them together. They began to meet. They continued to co-celebrate. They began to holiday together. And then one day, one of them suggested, “Why don’t we all build a building and live in it together – once again.”

The next time you see a chowk where children are playing and dismiss it as a waste of FSI and a collective bin, think again.