Continued from here.

Lohia Matri Seva Sadan at 296/B Rabindra Sarani is possibly the largest dormant building in Calcutta.

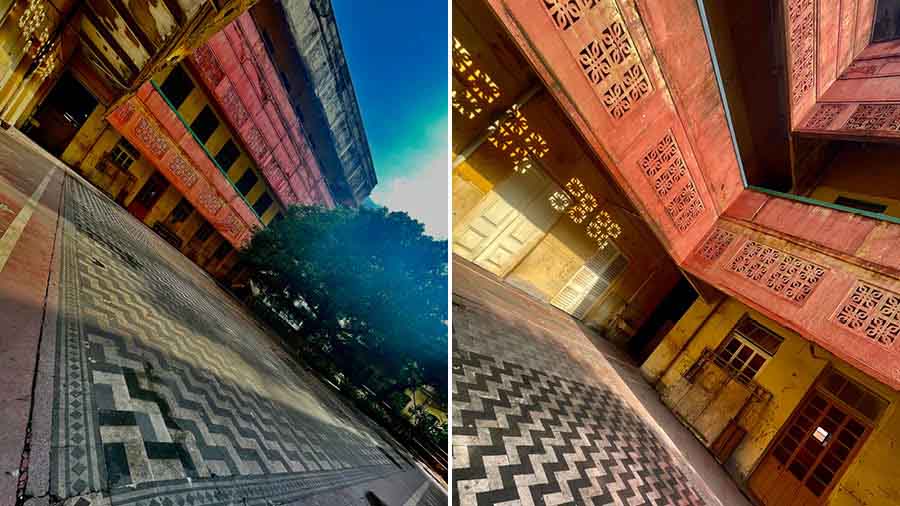

For the first 34 years of my life, I lived in a 500sq ft Mission Row home that comfortably supported four residents; by this analogy, the 1,00,000sq ft Lohia Matri Seva Sadan should be able to accommodate 800 residents and 500 floating staff; the 19 steps on its front façade can seat an estimated 250 people without anyone complaining ‘You are getting in my way’; for one to take a normal shot of this assembly without a wide angle lens would require the photographer to walk step-by-step backwards into Chitpur and risk being run over by a doodhwala cyclist; at least 40 cars can disappear into the driveway without using the reverse gear; if razed, the three storeys of the property can technically accommodate four 10-storeyed towers with some playing room in the middle.

Remember, that this was built to house just one family.

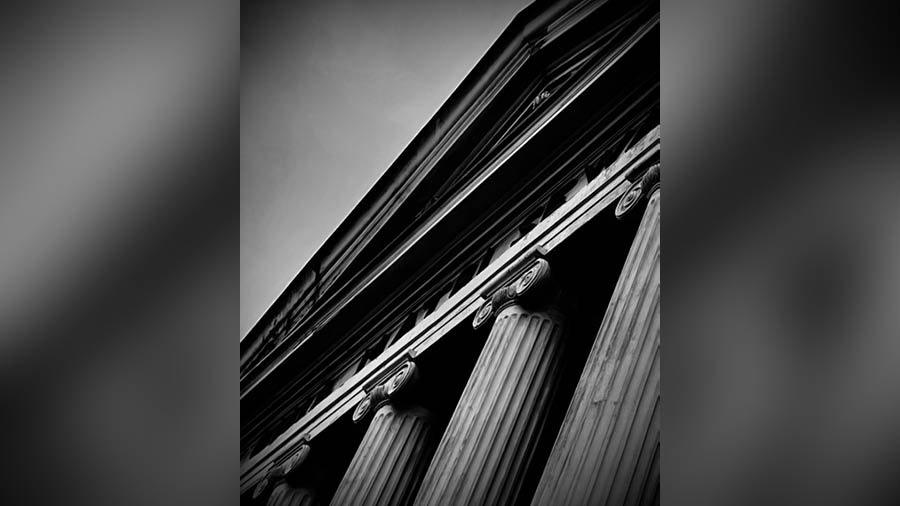

An introduction to this scale around modern-day grammar will make it possible to understand how the 19th century wealthy splendoured. Façade design influenced by the grandeur of a Green temple. Gate of this estate resembled that of Viceroy House, the seat of the British Empire (when the owner Babu Harekrishna Mullick was asked to remove the ‘offending’ lion on top of the gate, he refused, was taken to court, lost, appealed to the Privy Council, won, but by then he had won only to lose, the expenses having eaten into his wealth). I can ‘see’ him stoking on his bubble pipe in a starched and rippled cotton Panjabi with a horizontal leg perched lazily on the vertical, issuing a firman: ‘Dekhatay hobe amra-o aachhi.’

The courtyard of the house. Below, more glimpses of the mansion

This then was a home that Maharshi Debendranath up the road might have shaken his head privately and whispered ‘Ki korchen baboo!’ This then was a home that Ramakrishna Paramahansa must have heard of and possible chuckled ‘Shob maya.’ This then was a home that the Mullicks of Marble Palace might have said ‘Haan, bhaalo, kintu…’ This then was a home that the Viceroy would have summoned his immediate staff with an agitated, ‘Who does this baboo think he is?’ This then was a home where the patriarch would have walked different courtyards at different times of the day with aab-daars at full attention and respectful distance. This then was a home where different buildings in the rear were probably allocated to different women of the family, so it was entirely possibly that even a frequent visitor had only heard their names but never seen them. This then was a home where roshiks converged in a candle-light naachghor, partook paan, soaked in the fragrance, reclined on white bolsters placed on white padded sheets, nodded to the sarangi every few minutes and extolled their patron (‘Aapnaar moto keo hoyei ni!’). This then was a home where servants were employed around exclusive job profiles: to press feet, wind clocks, cut vegetables, man the main gate, light the evening lamp, sing devotional melodies by dusk, wipe the zameen twice a day, clear the ceilings of cobwebs, drive the carriage, feed the horses, apply hair oil, carry letters to different Chitpur homes, attend to children and accompany family members venturing out.

I was not alive to record these lives, but when you stand in the Lohia Matri Seva Sadan of 2023 – soaking the scale, space, style and stillness – you catch the whisper of the decades. Anyone who lived within the azeem sprawl of this architecture couldn’t have eked out a 16mm existence. If Calcutta was the City of Palaces; this home must have been among its most decadent.

It couldn’t last; it didn’t last. To grow the byabshaa, Harekrishna Mullick borrowed. The business trended down. The lifestyle needed to be protected; overheads and interest eroded net worth. A spiral started; the vastness of the borrowing was too large to be addressed; the great Mullick was compelled to sell the estate.

The new owner (Harendranath Seal from the legendary Mutty Lal Seal family) would probably have heard of the shaan of the past from the old retainers that now looked upon him as a saviour of traditions, sent by the Divine to restore mansion glory. Harenbabu borrowed (possibly to sustain the business and lifestyle). The glory days returned fleetingly. Inflows turned erratic, outflows were consistent. Creditors started making home appearances. Harenbabu was also forced to divest. An old Nimtolla Ghat Street resident told me that the new buyer permitted Harenbabu to stay on for some days out of aador after the sale had been concluded, but this was politely declined on moral grounds and the once-owner of 1,00,000sq ft moved his family and possessions to a two-room dwelling place on the same street. Maybe the staff wept when he was leaving; maybe he took a servant, maybe the women of this house now had to wash the family utensils, maybe Harenbabu now walked to get to places, and maybe he changed his commute so that he would no longer need to pass the estate he once owned. Maybes.

Pradyumna Mullick, son of the wealthy Manmatha Mullick, assumed estate control in lieu of the debts owed to him. If he was wealthy enough to buy, he must have been wealthy enough to flaunt. The new owner had a fetish – horses were passe; he owned 35 automobiles (10 Rolls Royces), presumably parked down the step, sending out a message to the Ezras, Birlas and Galstauns.

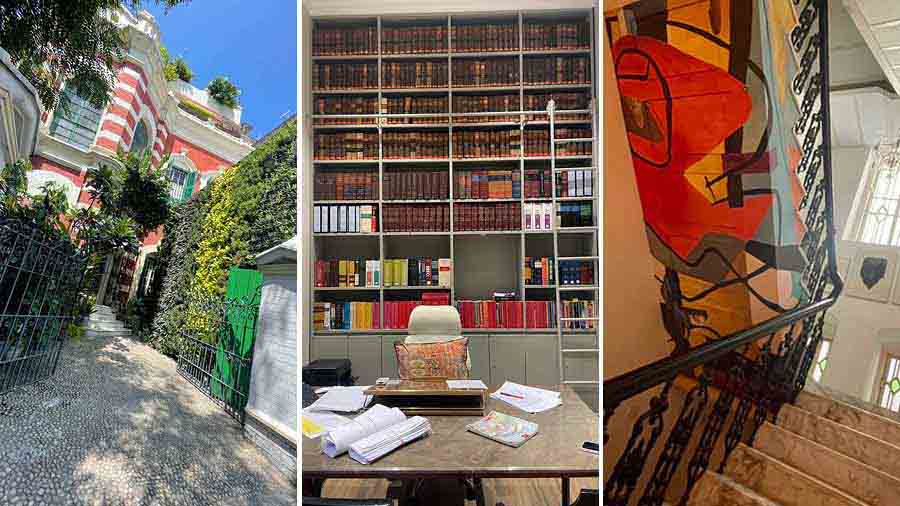

These landed babus probably had access to all creature comforts

of the time; what they lacked was a chief risk officer. Pradyumnababu

too overextended, borrowed, ran into a cash squeeze and was compelled to do

what his predecessors had done: put the biggest family jewel on the block. For

the third time, one of the largest private properties in the city changed

owners. The word was rife: womenfolk in the adjoining homes of Chitpur (the

Mullicks of Ghoriwala Building across, the Roys of Jorasanko Rajbati alongside)

whispered that the building was cursed; their servants repeated; the

neighbours believed.

The estate acquired a non-Bengali ownership – Kanehialal and Brijlal Lohia – in 1940. The Lohias from the jute business were more austere than their predecessors; they checked their daily parta; they knew exactly how many times over their income exceeded their expenditure for the day. The Lohias did not move in; they continued to live in considerably more modest circumstances and surprised the neighbourhood by transforming this large estate into a subsidised maternity hospital. What the Lohias may have otherwise spent by way of residential overheads if they had lived in LMSS was replaced by the subsidy they now paid to sustain maternity interventions. They continued to manage their business hands-on, a part of which provided the annual corpus to sustain this charity.

This story sustained for nearly seven decades; the maternity hospital provided competent and subsidised services (Rs 7,000 per caesarean delivery, all costs included, as recent as 2017). For the first 25 years, the premises generated unquestioned recall; if a family member was pregnant, it was a foregone conclusion that she would deliver at ‘Lohia Matri’; which explains how virtually every prominent Rajasthani in the city was brought into the world in this premises, including, as it is heard, Lakshmi Mittal of Arcelor-Mittal fame).

But times changed. Metro Rail provided easier cross-city connectivity; most paying customers moved to south Calcutta; Alipore and Kankurgachi became the new ‘Rajasthans’; regulatory compliances got stringent; professional retention became challenging. A maternity hospital that addressed 300 beds at peak declined to 30 by 2017 - ‘too much for too little.’ The charitable Lohias were now spending more in funding the overheads (municipal taxes, electricity, 30 doctors and 120 staff) than they were in direct maternity interventions. The Lohias recognised that times had changed; LMSS discontinued services in 2017. Lohia Charity Trust remains committed to revive this facility by working with prospective prominent health care brands, transforming its role from hands-on engagement and philanthropist to a de-risked lessor.

There is a sentimental innocent sitting inside of me. When I walked through the long room that was once the nahabatkhana-turned-subsidised maternity ward, I vacillated between feeling good and bad. One part of me felt that the grace and culture of an age had dissolved to never return; another part of me felt that the same facility had been repurposed from decadent opulence to general well-being; from a private luxury to a public facility; from the exclusive to the inclusive.

And this is precisely why LMSS needs to enter its fifth innings. If heritage and health care can collaborate yet again – through a more contemporary business model – this facility may showcase the resilience of a city that has often been given up for good but has surprised by standing up for the good instead and soldiering into the future.