Continued from here.

The Naktala Udayan Sangha pujo on Bengal’s Partition trauma (theme line Hridaypur or Heartland) warrants larger footfalls not only because it is re-archiving a fading neighbourhood memory but because the term ‘Partition horrors’ largely evokes recalls of what happened in Punjab and little of what happened to Bengalis. If there has to be a large upside form this pujo installation, then this it is: a wider realisation that we too have a rich — if less bloody — narrative on the subject

For all those who think nothing of flying to Amritsar to view the Partition Museum, the least one can do is to take the Metro to Masterda Surjya Sen station and walk 12 minutes to get to this pujo. I did not burst into tears here as I did in one of Amritsar’s Partition Museum rooms, but there was a dard. Some pujas you will take in with the eyes, some with the ears and some with the senses. This Naktala puja belongs to the third category. You may leave the puja after 25 minutes; the puja will never leave you.

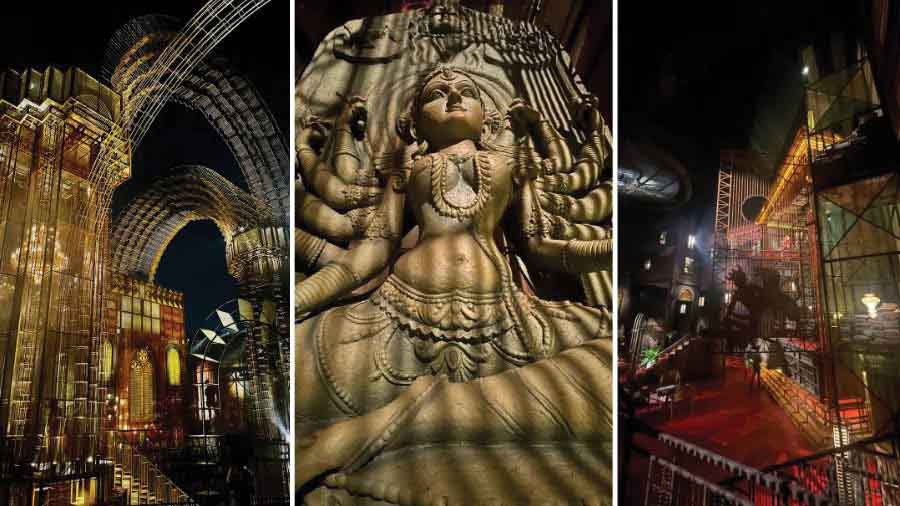

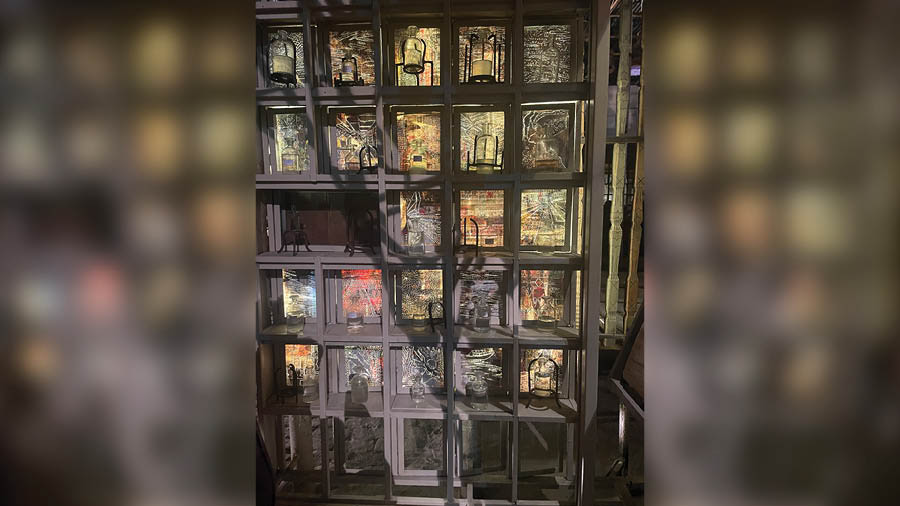

Installations at the puja (also below)

The Naktala puja will never ‘leave you’ because it is about people, that neighbourhood’s presence in Partition history, the spirit of the resettlers, the extent of their loss, memories of that loss and the unrealised yearning to see their land again. We – who consider displacement as yet another shift in cities on account of changing jobs with a provision to fly back across an extended weekend – will never know what it must have meant to leave at a 15-minute notice and never see their home again. From what was once a refugee’s fringe colony has emerged a bustling urban neighborhood where suddenly comes this puja and re-emphasises the inheritance of this loss (plagiarised from Kiran Desai’s book). The pin code of this neighbourhood is ‘Calcutta 47’. Ironically.

The Naktala pujo team has generated reasonable reading material including QR-coded downloadable content and a four-page broadsheet on the puja theme that one can pick for free at the pujo site. The pujo educates me: ‘This is the history of the zameen on which you are standing.’ The name was something I would hear in a high-pitched drone from precariously angled minibus drivers; from now on, I will speak of Naktala with some respect, knowing its role in a larger canvas.

More on the ‘honest’ bit. The Naktala puja committee assembled researchers to speak to residents; evidently some land had been allocated as a part of an official refugee settlement process while the rest was forcefully acquired (jobordokhol) with a disclaimer that even as this may have been wrong, it was the only alternative. Most researchers would have been pleased to leave the narrative there; they carried a mention of Muslim landowners whose properties had been encroached. ‘There was fairness in telling history the way it was and not how people would like to read,’ the curator said.

This brings me to the curator himself. Pradip Das. One would imagine that he chanced upon this puja theme through progressive thematic de-selection (Disneyworld no, rural Bengal no, women’s divine shakti no). The idea had been fermenting: in 2021, the Naktala pujo installation was a generalised approach to migration, involving the use of trunks and trains; in 2022, Pradip’s collaborative project comprised 40 neighbourhood women linked to migration; this year, the cooking was brutally direct – the Partition itself – following conversations with those who experienced it firsthand. ‘I always knew that there would be different layers, which explains how one got to this raw stage in 2023,’ said Pradip.

The Partition content was extracted across three months. Two memorable moments: during the Bangladesh research leg (during which water was collected from the Sitalakshya, Bishkhali and Kalijira rivers), a series of homes was shown to Naktala residents at which point one of them jumped out of her chair and ‘Ami ei bari-tay thaktam!’; on 8 August 2023, the research team interviewed octogenarian Nihari Bosu Banerjee (voice recorded) and three days later she was gone, almost as if she had ‘waited’ to hand in her narrative.

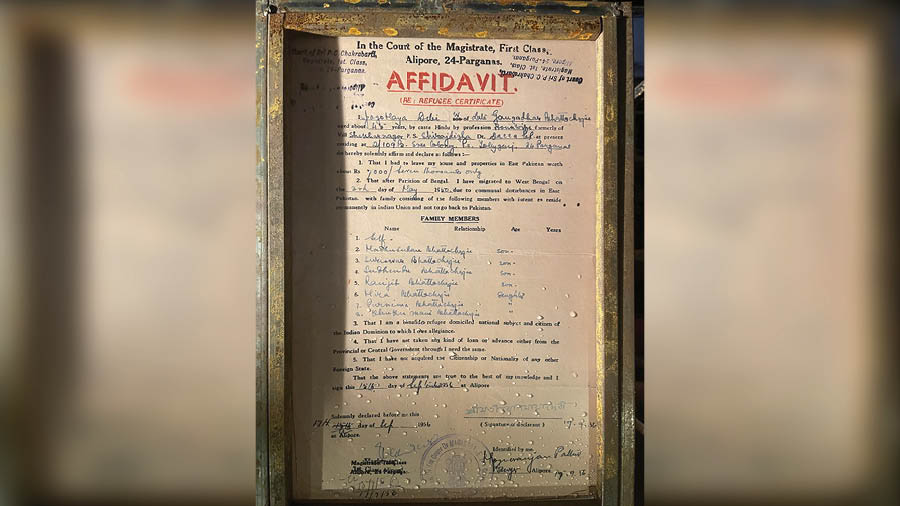

The research team commissioned a scanner on site, which yielded around 150 photographs and documents from Partition migrant families. Following the launch of the pujo, the subject has generated traction. ‘There are neighbourhood residents coming to say that ‘Apni amader family-r chhobi use korlen na?’ The entire subject has been rekindled. There is not only a wider interest, but enhanced participation and one has no idea where this could lead.’ says Pradip.

Two memorable anecdotes – a resident Mihir Sengupta spoke about visiting Sealdah station every day: ‘What if my siblings come? What if I get any news?’ The other anecdote is a bit longer: Naktala resident Biplab Basu heard this from his mother: ‘The people who worked on our fields were all Muslims. Whenever they got time between the work hours, they used to rest in our home yard and sit on the chairs given by Maa. She kept separate utensils for them. When the workers used to leave, Maa used to wash the place where the workers sat with cow dung to ‘remove impurities’. However, when the riots were at its peak, the workers gave us shelter in their houses. My parents hid in their blankets.’

My high point? The recitation in the background. The voice. The lilt. The words. The emotion. In an environment with neutral colour and low lighting, the clarity of the voice – almost like Naktala’s anthem – spooled and unspooled. If you hear it once and know the backstory, this may be difficult to vacuum.

My recommendation to anyone visiting this pujo would be to request organisers to meet a resident whose parents came from opaar. That direct engagement may do more in terms of experience value than more than 1000 words I have written here. If it does – as I am sure it will – the experience will have transmuted from a personal grief to a shared tragedy.

And through that symbiotic understanding of pain, loss, sacrifice and struggle could emerge something that most of us are gradually giving up on: a better world.

Theme song of the pujo

Jodi sondhye namar agay bari phirey aashi

Tobey chhaya ronga chhelebela dekhte pabo

Je shrabon choley jai prem e ghun dhorey jaai

Shei shoda maati gondho ki bhabey nebo

Somoy bileen hoye chokh paltaye koi

Bhalo thaak shob kichhu Hridaypur-e

Amar maa-er kachhe jaa kichu rakha ache

Shiulir mala kore gethey rekho tarey.

Sarosh er pal orey digontey roddur-e

Baka chand mone rakhe bholey na tarey.

Somoy bileen hoye chokh paltaye koi

Bhalo thak shob kichhu Hridaypur-e

Translation

If I return home before evening

Only then will I see the colorful childhood

The love that goes away, the love takes hold

How to take that soft soil smell?

Time passes by changing eyes

Be well, everything in Hridaypur

All that my mother has kept

Garland like the shiuli and put it on the wire

A flock of sarus flies to the sun on the horizon

The crooked moon remembers not, forgets it

Time passes by changing eyes

Be well, everything in Hridaypur