Continued from here.

I walked into the landed estate of Badan Chand Roy not as much to soak in the rich legacy of its 166 pujo years, but to ask one question: Why did this illustrious family skip the Durga Pujo in the 89th year?

This impressive estate (also referred to as ‘Colootola Roy bari’) can be accessed through Phears Lane (Chuna Gali) or Chittaranjan Avenue-Kaviraj Row (where Ganesh Pyne once lived).

The person who speaks on behalf of the family is the 84-year-old Pashupati Roy, the family’s oldest. He is the only family survivor privy to the 1946 circumstances that led the Roy family elders to send the word out that ‘Ei baar pujo hobe na.’

Pashupati babu starts: “Shunun! In 1946, aamader desh was divided by communal violence. The Muslim League was demanding a separate homeland for Muslims and the centre of that violence was amader Calcutta. The high point of that communal violence was Direct Action Day on August 16.”

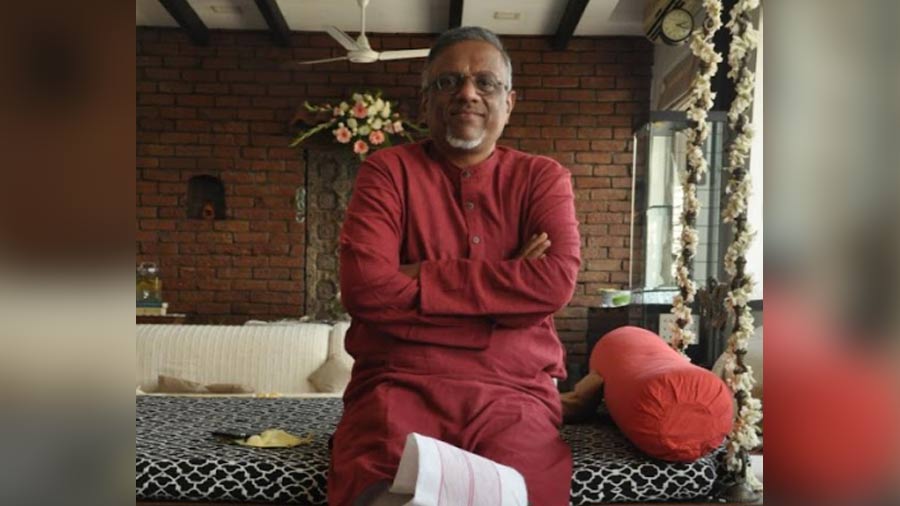

Glimpses of the mansion (also below)

The fine print of Calcutta’s darkest story in 100 years has been extensively recorded. Four days of the Great Calcutta Killing resulted in 5,000 to 10,000 dead (at least four times the number that officially died in the Bhopal gas tragedy if it provides any sense of scale) and 15,000 wounded. Living octogenarians recall slashed bodies, windows and gates being shut across the city, families sharing food and fear everywhere (Jyoti Basu was stuck in a home near Sealdah and took three days to return home).

The Roy family found itself at the epicentre of this communal cauldron — possibly the largest and most prosperous Hindu home in a predominantly Muslim neighbourhood. The family had always recognised the awkwardness of their address; this occasion made it even more so. Within a day the Roy poribaar — about 30 family members and 70 domestic staff — had recognised that this clash was different in scale, scope, and suddenness. “On 17 August 1946,” recalls Pashupatibabu, “our poribar decided that it would be safer to leave our estate to go to some place more secure”.

I can ‘hear’ what Pashupatibabu has not described. The meetings in the uthon between the family elders; domestic staff sent periodically to the uppermost point to look down the street for tell-tale threats; family members assigned specific responsibilities; family women being told that ‘Shob pack kore ready rakho, kokhon berote hobe kichhu theek nei’; family members being asked to engage with the police for guidance; family members being asked to talk to Medical College for refuge; domestic staff being asked to ensure that all dorja-janala remained fastened; a young mother being told to keep the children safe (‘Ekhane-okhane jeno doude na jay’).

Pashupatibabu again: “It was 3.30 in the afternoon when the family sensed a safe moment to move out with whatever we could carry. We assumed we would be back within a day, or a week. The police would get a grip on things and the mahaul would quieten. While proceeding hurriedly down the bylane towards Medical College, we saw something and felt we had got it hugely wrong: a hundred-strong mob was running towards us, waving swords above their heads and chanting slogans.”

The mob may have proceeded with its intent but for the sudden appearance of Shamsu miya. A longstanding neighbour of the Roys. He probably saw what was transpiring from his window off Phears Lane; he had the option of first hurriedly shutting all the windows and doors and instructing his family to huddle in one room, waiting for the mob to roll over. He ran down the stairs instead. Alone. Stood in the middle of the street. The advancing killers on one side. The terror-stricken group (elderly, women, children, and domestic helpers) on the other.

The mob should have elbowed Shamsu miya aside — one of their own, in a limited sense — and proceeded with their agenda. They de-accelerated in the face of this single man. ‘Bhai hai yeh sab… hamara!’ Shamsu miya said (recounted by Pashupatibabu). ‘They are fleeing their house and we will kill them,’ came the rejoinder. ‘Why will they flee their own house?’ Shamsu miya countered. ‘See the windows, they are all closed,’ he was told.

A seven-year-old Pashupati was probably dwarfed in the 10th row of the family huddle and could possibly see no more than familiar family contours. “I was tightly holding my mother’s fingers, while all of them were looking over the shoulder of the person in front to see what was transpiring between Shamsu miya and the 'mob'. After some minutes, Shamsu miya turned. He motioned hurriedly to the Roy family standing behind him with his hands to move. The 'mob' had relented. Pashupatibabu says 77 years later: ‘I don’t know what arrangement Shamsu miya worked out. Maybe he said, ‘You want to loot, go inside, and take as much as you want but I will not let you touch the family.’ That is how aamra save holam.”

The Roy family spent the night of 17 August 1946 on one of the uppermost storeys of Medical College with other escapees (total 250). Probably slept on the floor. Probably slept with their biceps serving as pillows. Probably never slept at all because ‘At 6pm, there was a ripple of terror that a mob was on its way to Medical College to kill us all.’ Probably felt that if they never came at 6pm then they could any minute thereafter.

The family was always going to be a sitting target so after a night, it moved — all 100, domestic staff and all — to a relative’s residence on College Street (‘tram liner o-paar’). The stopover must have been too small to hold the Roy clan brought up on a one-bigha estate, so after a brief stay the family made started fanning out — some members went to residences of their in-laws, some to distant relatives and that is how the Roy clan methodically scattered — not to load enough on any family, finding small places within, ensuring that the accommodating family was compensated and spending as many hours outside home that would prevent existing space dynamics. The child Pashupati and parents moved to Barkaram Street in Bowbazar, then BT Road (‘An uncle gave us refuge’) and then to Paikpara. This time for a year.

In a world where we get homesick in days, it would be worth remembering that the Roys of Colootola converged from various parts of Calcutta to their family bari in the same city only after Independence had been achieved. Much of this inducement came from Shamsu miya himself. He reasoned with the family elders: “What are you worrying about? Better times are ahead. All you need to do is come and live inside your great bari and the splendour of the past will return. Aami aachhi toh!’

Following the Roy family’s return in 1947, some 50 neighbourhood residents went street to street, sending out a message that all was safe and that it was time for others to return as well. This time though the family was taking no chances; it deputed 50 Gurkhas for their security, as did other Hindu homes in the neighbourhood (families of Sagar Dutta, Debendra Mullick, Gadaibabu and Sens). Besides, the police commissioner deployed a protection team at the Roy residence for a year with the provision that ‘Ei baar kintu pujo kortei hobe.’ The Durga Pujo that followed — October 1947 — was more than just a ritual compliance on the freshly inhabited premises. Says Pashupatibabu: ‘It was a revenge puja of sorts jei rokom bola hoy. We had a point to prove. That the spirit of worship, peace, good neighbourliness and a new India would endure and prevail.’

After this story, every other Roy bari pujo detail comes off like an anti-climax: all women of the household wear nose rings with three pearls during the festival; Mackintosh Burn designed and constructed this premises in 1835; the Roys moved in a year after the Dakshineshwar Temple was built; 25 family members live within today; 600 people are fed on Ashtami; there are ‘30-40 rooms on this premises’ because no one has cared to count; the celebration of sharodiyo pujo was written into the family will by the ancestor Mathur Mohan Roy; one of their caged residential birds lived 45 years; from Sashthi onwards there is a special onusthaan — jatra or comedy — each evening for anyone who wishes to come.

When I am leaving, Pashupatibabu tells me (here he raises his vertical palm sideways to his forehead): ‘Kintu eta likhben that all these pujas are the result of Devi maa and… Shamsu miya.’ He inclines his head; the tip of his index finger touches the forehead.

This then is not the story of a property as it was; it is the story of a country as it can be.