Little Mukul’s quest for Sonar Kella ended at the Golden Fortress. Mine did not. At least not at first when I arrived in Jaisalmer, carrying a backpack laden with 30 years of expectations.

Visiting “Sonar Kella” or the Jaisalmer Fort was on my bucket list from the time I was little enough to fit inside a bucket. I had first watched Satyajit Ray’s iconic film, Sonar Kella, which led me to the eponymous book.

The children’s holiday special on Doordarshan called Chhuti-Chhuti, was possibly the only thing we were allowed to watch on TV those days. It was one magical hour every weekday that children in Bengal and their parents looked forward to equally. Adults have always succumbed to the lure of screen nannies to get their pesky brood off their hands, especially during interminably long summer breaks when there was no school to pack us off to, and it was too hot to let us play outside.

On a hot May afternoon when I was about eight, the film was shown in three parts over three days. I remember being unable to fall asleep the first and second nights, so enamoured was I of the story of the little jatishwar (reincarnated boy), the train journeys, the dushtu lok (bad men), the handsome detective, telepathy, the camel ride chase, and, of course, the fort!

Sonar Kella fired up my imagination like nothing else could, not even Enid Blyton, not even Tinkle or Tintin, and Harry Potter didn’t exist. A couple of years later, I read the book and loved it so much that I would hug it to sleep every night for a while. It is, therefore, quite a travesty that it took me so long to finally get to Jaisalmer. Life happened, what else can I say?

So, some 30 years on, I landed in Jaisalmer just before the world went into lockdown.

Driving to our hotel from Jaisalmer airport — a military airbase that has been opened to commercial airlines only a couple of years back — the fort suddenly came into view. Of course it didn’t glow like gold, but it was golden alright, built from a yellow sandstone that is native to these arid parts. The fort looked massive, and majestic.

Despite the missing “e” from “Welcome”, we welcomed ourselves to the WelcomHeritage Mandir Palace Hotel in Gandhi Chowk, because it promised a grand view of the fort from its open-air dining area. The hotel was a lovely choice, the view of the fort in the evening, lovelier still. An ethereal golden glow encircled the fort, making it seem just as magical as my childhood imagination. That night, I felt some of the flutter from that summer of 1990.

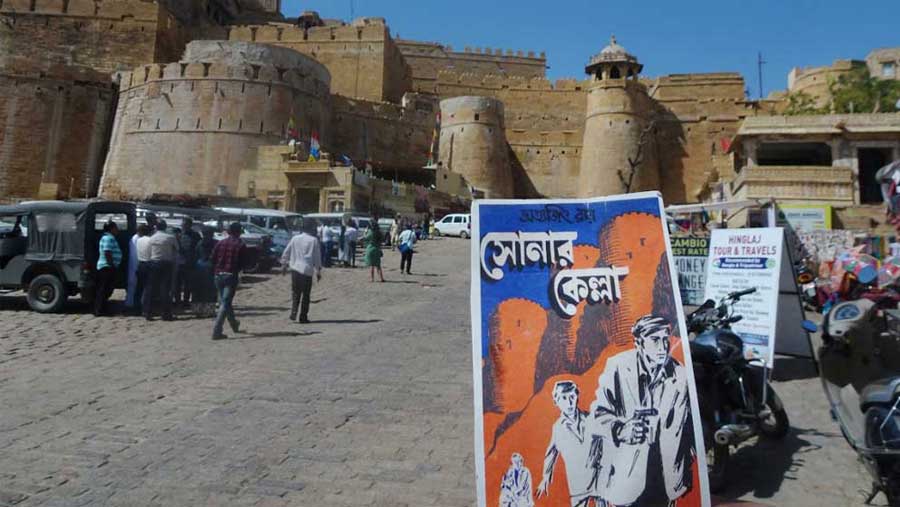

Entering Sonar Kella, Feluda for company.

The next morning, we walked through the heart of Jaisalmer to reach the fort, dodging brash two-wheelers and bovine two-horners with equal trepidation. Right from outside the gate, tourist guides started flocking to us, offering to tell us all in just Rs 100. Of course, I had read up enough about this fort to act as a guide myself. But one fellow was smarter than the rest. Hearing us converse in Bengali, he made us an offer we couldn’t refuse. “I’ll show you Mukul-bari.” We promptly hired him, and off we went, through the massive gates, into Sonar Kella.

The fort has many interesting stories, Jain temples, palaces, a museum called Baa Ri Haveli, and other attractions typical of the forts of Rajasthan. But what really sets Jaisalmer Fort apart is that it is the only “living fort” in India, as the guides there will never tire of telling you. There are some 4,000 people living inside the fort. There are homes, hotels, cafes, eateries and bakeries, and shops selling everything from textiles and t-shirts to curios and artwork.

The golden walls of the fort are hidden behind everything from clothes to carpets, Rajasthani dolls to folk paintings.

We did the touristy things, clicked pictures from ornate balconies and latticed windows, posed with local turbans on our heads and admired the pots and pans of a munshi’s house that was on display.

And then the guide took us to “Mukul-bari”, or the spot where Ray filmed the final scenes, when little Mukul finds the home from his previous birth and his quest ends. On the way, our guide told us how the people of Jaisalmer, especially those engaged in the tourism industry, consider Satyajit Ray a god.

Mukul-bari or the ruins that are still standing.

“Before he made his film, no one knew about this fort, now we get so many tourists only because he called it sone ka killa. Not just Bengalis, even foreigners come here because he is famous all over the world,” our guide beamed. Before the 1970s, Jaisalmer Fort was known as Trikuta, because the fort stands on Trikuta Hill. One film changed the fate of an entire city.

Chatting and negotiating our way through narrow lanes laden with merchandise, we arrived at Mukul-bari, or what is left of it. Much of it is really just ruins, but one set of steps is intact, as well as the little lane where the villain is finally captured.

It was a dream come true.

Or was it? This fort was nothing like the Sonar Kella I was looking for — Mukul’s Sonar Kella. This was just a buzzing hub of human habitation bursting at the ramparts, where even the golden walls of the fort were hidden behind bright bed sheets and brighter table runners up for sale. Too many bikes, too many people, too much rubbish, too many hoardings, too many cows, too many shops, too many smells — the expectation and reality were clearly at odds.

I consoled myself by buying a yellow stone bowl just like the one shown in the film. For dinner that evening, we decided to try Restaurant Romany, the top-rated restaurant of Jaisalmer on TripAdvisor. While walking back, we crossed the fort’s entrance. The gates were wide open.

It suddenly occurred to us that because this is a “living fort”, unlike other forts of India which are heritage properties and are closed to the public after visiting hours, this one must always remain open. Because people live here. It was about 9.45pm, quite late for a small town, but we decided to walk in and take a quick look. And then my dream came true.

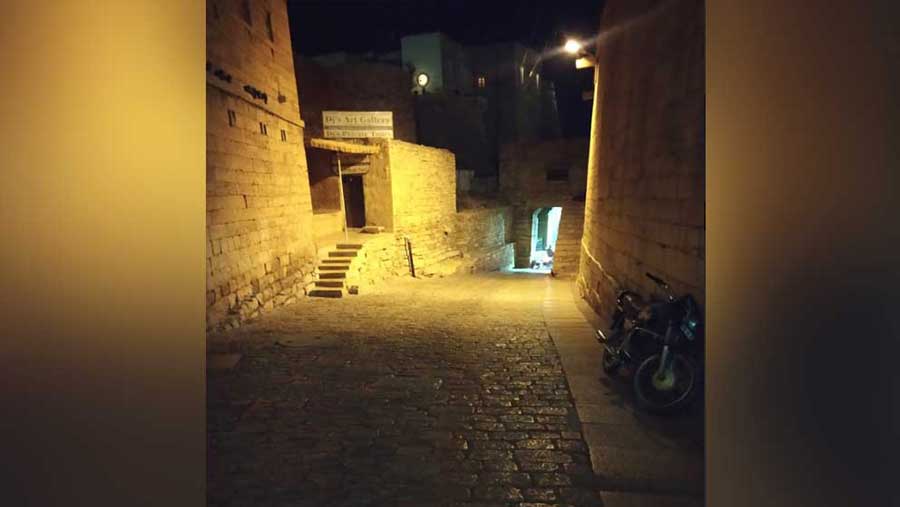

Desolate lanes inside Sonar Kella, with a mystery lurking in every shadowy corner.

Jaisalmer Fort by night is the fort we know — uninhabited, serene, beautiful, perhaps a little aloof, with a tinge of sinister in the air. As we walked with silent feet, I noticed the cobblestones beneath me for the first time, shiny with hundreds of years of traffic. Somewhere a nightbird screeched. A rat scurried past us and disappeared into the fuzzy darkness. Above us, the huge walls of the fort glowed majestic, but the lanes were mostly empty. The shadows of the huge walls wrapped every bend in the road in mystery and romance, and the silence really was golden. I had found my Sonar Kella.

Sonar Kella by night.