As a Kolkata joy-walker, I seek candid pedestrian moments and arresting facades. I capture images on my iPhone, transfer them to my Instagram page and intend to publish a book.

My recurring theme is the splendour of a city in selective decay: the emergence of a fascinating wall shade after decades of paint and peel; the colour of rust on a heritage mansion gate and the gentle curve of a faded arch.

A new dimension has emerged for my photographic attention: restored heritage mansions, newly painted structures and façade uplighters. Suddenly, my interpretation of the city’s heritage grammar has had to be revised: the dull red has competition from cream and gold; the rusted mansion gate has been repainted black and gold; there is a greater inducement to shoot street pictures after dark to capture new uplighters.

A watershed heritage preservation moment

The agency responsible for this dramatic transformation is Kolkata Police; the individual credited for having resuscitated the city’s flagging heritage movement is its former commissioner. This is a watershed heritage preservation moment; if Kolkata Police can transform crumbling structures into heritage showpieces, then a number of public, private and individual property owners will have a case study for replication.

The excuse can no longer be ‘Let us break it down and build a multi-storey’; there is a possibility that more owners may say, ‘There is a romance in a restored property that enhances neighbourhood pride.’

If you need a validation of the commitment of Kolkata Police to this cause, consider just two realities: the range of restored or work-in-progress police properties (Jorabagan Traffic Guard, Sealdah Traffic Guard, Sojourn Guest House, Park Street Police Station, New Market Police Station, Calcutta Police Museum, Shyambazar Traffic Guard and, by an extended licence, Swami Vivekananda State Police Academy in Barrackpore) and the fact that Kolkata Police recently created a Heritage Committee to transform a one-off exercise into a sustainable movement.

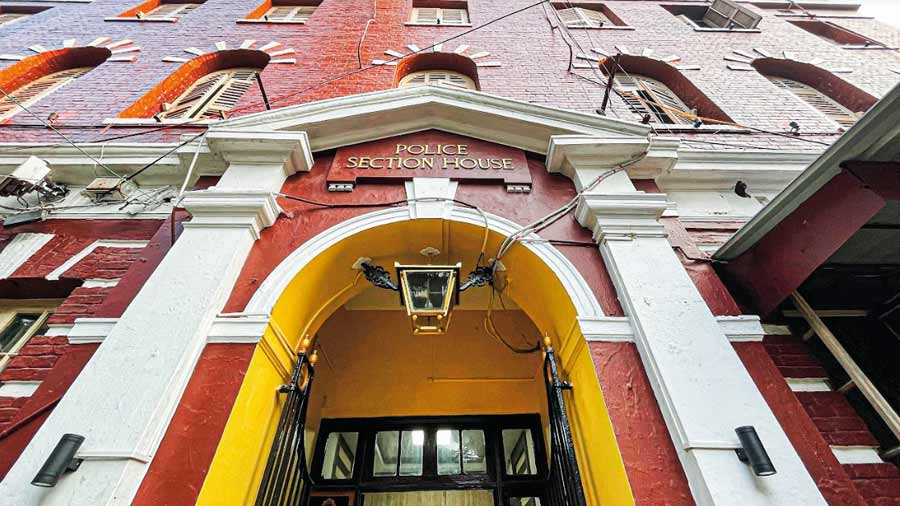

Park Street Police Station: This neo-classical building is a double storied structure, rectangular in plan with a wide front porch. The porch has an arcade of five semi-circular arches on the ground floor and a verandah on the first floor with ornamental cast iron railings and timber louvered screens, interspersed by Tuscan columns TT Archives

Portrait of police addresses as selfie stunners

For generations, a new possibility has arisen: all those who walk past Convent Road are likely to stop in their tracks and take selfies against the backdrop of the romantic Sealdah Traffic Guard bungalow (a police officer has been appointed to chaperone guests on a conducted heritage tour inside, would you believe!). Residents of the sepia Sovabazar Street are likely to refer to the Jorabagan Traffic Guard as their principal neighbourhood landmark. Visitors will discover a fascinating world inside what was once the home of Raja Rammohun Roy but is now an inspiring Police Museum. The arch, metalled gate and painted brick wall of Park Street Police Station are selfie stunners. When completed, the grilled verandah of Shyambazar Traffic Guard is likely to attract more visitors with cameras than traffic violators seeking a reprieve. The person in charge of the West Bengal State Police Academy is likely to be inundated with winter picnic requests at the Downtown Abbey-like estate replica in Barrackpore.

Sealdah Traffic Guard: This house had a rich library and was also used as a public space for socio-political meetings, including several Swarajya Party sessions. In 1970 the property was acquired by the commissioner of police for family quarters of subordinate police personnel TT Archives

It all began in Barrackpore

I tracked down the man behind this reinvention – Soumen Mitra, former commissioner of police (CP). He could have preferred a status quo; he could have said ‘Notun jhaamela maathay key nebey?’; he could have said ‘Where are the funds?’

The story is that when he was dispatched to Barrackpore to train young police staff, he was awed by history’s overhang. The imposing estate was conceived, pushed and funded by the Marquess of Wellesley who set about building grand estates when his job was to widen trade and strengthen the bottomline of his employer (East India Company). This is where the Governor General took the weekend two-hour phaeton from his Esplanade estate to Barrackpore. The weekend retreat with its adjacent river was where Lady Canning painted canvases. This is where the Marquess of Hastings relocated a marbled fountain from Agra and Governor House. This is where rooms were larger than tennis courts, ceilings were ‘G+2’ and doors needed the strength of two firm hands to be shut.

Soumen’s imagination was kindled; he saw the place not as it was but what it could be. He initiated the restoration with a nominal grant; as the work expanded, more funds began to come in. The place began to transform. The mansion began to stir to life.

This is a watershed heritage preservation moment; if Kolkata Police can transform crumbling structures into heritage showpieces, then a number of public, private and individual property owners will have a case study for replication.

When Soumen was transferred to Kolkata to assume the position of CP, the net practice at Barrackpore had prepared him for the big game. Within the space of a few months, the man had listed out all Kolkata police properties that were heritage; he had embarked on the largest concurrent restoration exercise in the multi-century history of the city’s police force.

As a street historian and joy-walker, these are reasons for elation: the officers at Jorabagan Traffic Guard are not interested in shooing visitors like you and me off their premises; there is a quiet interest in anyone staring at a tiled flooring or taking a grille picture. The officer at Sealdah Traffic Guard is more likely to say ‘Cholun, aami aapnakey jaayga ta dekhacchi’. The officer at Shyambazar Traffic Guard is more likely to say ‘Chhobi tuley ektu dekhiye jaabeyn’, more out of photographic interest than administrative protocol.

Jorabagan Traffic Guard: This building belonged to Raja Janakinath Roy of Bhagyakul, Bangladesh. During the Naxal movement, it was occupied by the Central Reserve Force. In 1980 the Jorabagan Traffic Guard, which was earlier functioning from a house owned by the Nawab of Murshidabad at 74 Nimtala Street, shifted to this premises Mudar Patherya; (right) TT archives

Mystery of the missing marble fountain

The story that interests me more than most is how the fountain was recovered and restored in Barrackpore. Soumen chanced upon the mention of a marble fountain transported from Agra Fort from the diary of the Marquess of Hastings: how he first found it in shambles within the Agra Fort, how he had been fascinated by the idea of its restoration, how he desired to remove to Kolkata, how he was apprehensive that this relocation could anger local residents and how his fears were put to rest by one of his advisors that not even two local residents would bother to object. The fountain was installed in the southern garden of the Government House (Raj Bhavan) but the silted water from the Hooghly affected the showpiece, after which it was removed to Barrackpore where the Governor General leisured.

This provoked Soumen’s interest. He began to look around for this celebrated Shah Jahan-vintage fountain on the Barrackpore premises. The fountain could not be found. The word was sent out. A larger team was engaged in looking for where this fountain may lie. The search proved successful; someone extracted white marble from beneath leaves and debris of the grounds of the Brigade Hospital. The intricate inlay work was visible; Soumen engaged a local plumber who reactivated the fountain.

Today, when you visit Barrackpore, you can tell yourself that what you see in front of you was once a gleam of the eye of Shah Jahan, the man who went on to build the Taj Mahal.

The transformed southern façade of the governor general’s weekend retreat at Latbagan, Barrackpore. TT Archives

When we play the game for pride, anything can happen

I like what Soumen said: ‘There is a message that when we play the game for pride, anything can happen. Kolkatans respond to a sense of pride stronger than other inducements. These restored properties address precisely that part of the Kolkatan’s psyche: an awareness of our rich heritage, the ability to improve realities and do everything possible to become great again.’

Mudar Patherya is a romantic who revels in Kolkata anecdotes, pictures, bylanes, characters and memorabilia.