The river caresses the land as it burbles past the village. Every year, there comes a season when the Ajay also touches the idols in affectionate welcome, its gentle slosh hiding the pain of farewell after four days of festive piety. It has been doing that for years, for more than two centuries. That’s how far the Durga Puja of Kalanpur village goes back.

The Ajay will welcome the idols into its depths too this year, early next month, sometime in the first week of October, after the married women of the house have caught a reflection of the goddess in a mirror and put vermilion on each other.

“Yes, our puja is over 200 years old,” Kalyan Chowdhury, who lives near the village, in what is modern-day East Burdwan, told My Kolkata. “It is an attempt at keeping alive ancient tradition and rituals, and living the happiness of getting together.”

The retired headmaster is a descendant of Shyamsundar Chowdhury of the House of Chowdhurys, the zamindar who started the puja in this village, now under Mangalkote police station, a few hours’ drive from Kolkata. Much has changed since — the landlords no longer wield the influence they used to; the kings of Barddhaman, their overlords who ruled over a vast territory that now covers several districts, remain only as memory, as part of history, long divested of their royalty. Social hierarchies have changed too, shaped and reconfigured by the economics of power and politics. So have lifestyles and cultures. But the puja has not only survived, it also brings together all the branches of the Chowdhury family for a few days. So come, let’s take a look; but first, a walk through this village that the river caresses. Without the river, the village may not have been there.

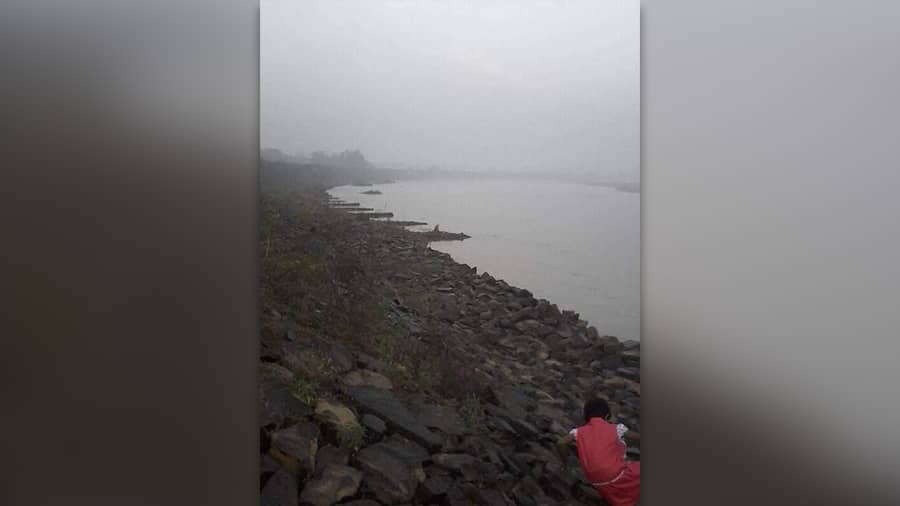

The banks of the Ajay river

‘Affectionate’ river

The Ajay has flown between Burdwan and its adjoining Birbhum district for centuries, longer than anybody can remember. “Baari aamaar bhangon dhora/Ajay nadi’r baanke/Jal jekhaney sohag bhore/ sthal ke ghirey rakhey,” poet Kumud Ranjan Mullick, who lived in the neighbouring village of Kogram till about half a century back, would write, musing on his “rundown home by a bend in the river that affectionately hugs the land”. The words — and the approximate translation — capture the spatial and spiritual relationship the villages around the Ajay have with the river, a part of the conscious topography of the terrain, like a presence that is assumed. Still, when the first autumn winds blow across the banks and the strands of catkins (kaash phool) sway in the breeze, a chorus of downy white against green, a ripple spreads from door to door. It’s the signal for Kalanpur to get ready because the Pujas are near.

When the first autumn winds blow across the banks of the Ajay, and the strands of ‘kaash phool’ sway in the breeze, it’s a signal for Kalanpur to get ready for the puja TT archives

Two centuries ago, Shyamsundar too must have felt a similar ripple one autumn day, sometime in the closing years of the 18th century. Shyamsundar, who had already started the daily worship of the god Damodar, another name of Narayana, considered the supreme being of Vaishnavism, decided to start a Durga Puja at his home in Kalanpur. So he built another temple where the goddess would be worshipped. His grandson, Surjyakanta Chowdhury, would carry on the practice that Shyamsundar started — of the daily customary offerings to Damodar and worship of the goddess Durga every autumn — before later generations would take up the responsibility. The terracotta work on the Durga temple has faded, but the main temple still stands. And the 200-year-old ritual of sacrificing a goat on Saptami and Navami is still followed. Some branches of the wider Chowdhury clan had tried to stop the animal sacrifice but every time they did, some misfortune would befall these families. It must have been pure coincidence but the result has been that goats are still sacrificed during Durga Puja in this palatial house of the zamindars of Kalanpur.

At times, nature would play truant. Like it did in 1978 when catastrophic floods nearly ended a tradition that had lasted over 180 years, as the Puja could not be held with an idol. Instead, offerings were made to a pot, a symbolic representation of the goddess.

Celebration, with a difference

Over the years, the zamindars of Kalanpur would introduce different practices into their puja. For one, the sound of dholaks, a folk percussion instrument played with fingers, would reverberate across the village instead of the usual dhaaks, drums played with two sticks. The beats of the dhaak, integral to Durga Puja elsewhere in Bengal, are banned in Kalanpur through the Puja days, from Sashthi to Dashami. It’s not known why they were banned, but it was certainly a visible expression of divergence, deliberate or otherwise.

The beats of the dhaak, integral to Durga Puja elsewhere in Bengal, are banned in Kalanpur through the Puja days. Instead, the dholak is played

Then, fish would be offered as bhog (offering) to the deity, prepared by the women of the house, unusual in those days when thakurs (male professional cooks) would be hired. The thakurs would, of course, prepare the main community meals served during the puja.

“The bhog offerings for the puja of Damodar and the four days of the Durga Puja were all cooked by the women of the house,” confirmed Mira Chowdhury, who has been associated with the puja for over 60 years.

The festive spirit would continue till Kali Puja, which too would be celebrated in the village where the influence of Tantra and Shakta rituals run deep. A likely reason behind the tradition of worshipping Kali is the clerks of this zamindari estate were descendants of Kamalakanta, the late 18th-century Shakta poet and yogi who was a devotee of the demon-slayer goddess.

Syncretic tradition

In a way Kalanpur, also called Kalyanpur by many villagers, represented a fusion of different traditions within Hindu religious beliefs: the Vaishnavite tradition of Narayana worship and the worship of Kali, popular in other villages like Ilambazar, Ullaspur, Purandarpur, all on the Burdwan side of the Ajay’s bank. On the other side of the river, the folk music of Birbhum’s Baul singers represented another type of syncretism — of Sufism and Vaishnavism. The river didn’t merely hug the houses on its banks; it symbolised a tradition of diversity.

The decorated entrance of the house

With time, new stories would emerge about the village, its old houses and their ancient traditions, some heart-warming, others not so. An interesting nugget from the past gives a glimpse of dwelling patterns then, a time when visible social chasms meant the less privileged were consigned to the margins. Near the village entrance lived the lethels, the zamindar’s army of musclemen, who used lathis (wooden rods) as their weapon of compliance. After the houses of the lethels stood the quarters where the blacksmiths stayed, followed by the potters. One had to cross these dwellings to reach the palatial house of the zamindar. On one corner lived the Muslim residents of the village, while the farmers lived in huts behind the zamindar’s house. The shoemakers lived on the outskirts. The social hierarchies and religious divisions have since reduced; and wide asphalted roads now lead to the village, not nearly as accessible even a decade back.

Towards inclusivity

Another story, this time more inclusive, relates to food. In the old days, luchi, one of the few items to cut across every man-made division in Bengal, would be fried for Muslim subjects on the day of Ekadashi.

The Puja-day menu, prepared for everyone in the extended Chowdhury family as well as for all the villagers, also reflected a sense of uniqueness. One of the items would be Kochu-r Molom, unique to this place, where kochu, a type of edible root, would be brought from Guskara, a town and municipality in East Burdwan, and then used to make a soft spicy curry. Although not available nowadays, the black kalai daal was a favourite too. Because of its black colour, this daal would also be called Kali kalai.

For those who played a direct part in the Puja, there would be material benefits too. The zamindar’s house would arrange for land to be gifted to the musicians who played the dholak and other instruments like the kasa, and also for those who built the idol.

On Ekadashi, local residents would bring fish to the zamindar’s house and, in return, receive naru, fudge prepared with coconut and flavoured with either sugar or jaggery, and murki, made from special puffed rice.

Another account has a whiff of the implausible, but sometimes things do happen that defy conventional logic. The story goes that when a descendant of Shyamsundar opened the sanctum of the temple to Damodar for the first time, the entire room was filled with the scent of incense sticks. The sanctum had not been opened for years.

Among the more well-known of the Chowdhury clan who organised the Puja was the late Dr Ramaprasad Chowdhury, a gold medallist from Calcutta Medical College, who had studied under Dr Bidhan Chandra Roy, former chief minister and architect of modern West Bengal. Ramaprasad has left behind his personal impressions in writings, which offer a glimpse into the Kalanpur Puja.

Sense of togetherness

Sunil Chowdhury, another descendant of the family, recalled a change in mindset that had taken place over the years. “For some time, shariks (individual branches of the family) would take turns every year to organise the puja. Now, again, they have started organising the puja together as one. It is believed that this would bring the people closer,” Sunil, who appears to be in his eighties, told My Kolkata.

The zamindari era has long gone, but the Durga Puja still draws the descendants of the zamindars of Kalanpur. They remain there, “living their togetherness”, joining in the celebration of a shared heritage till the idol is lowered gently into the waters of the Ajay on the day of Visarjan. Widening ripples slosh over the bank as the river welcomes the goddess.