Ismail bhai Khatri, who notices all of us taking off our footwear at his doorstep, barely gives more than an imperceptible nod, welcoming us into his quarters. The award-winning artisan who holds a Hon. D. Art from Montfort University, UK, is used to tourists from all over the world dropping into his studio, which is tucked in the bylanes of Ajrakhpur in Bhuj, in the Kutch district of Gujarat. A 9th generation master artisan, Ismail has now passed on the subtle block printing art of Ajrakh, that needs a great deal of time and patience, to his sons and grandsons. As we step inside, we are greeted by tall, unending piles of Ajrakh material that are unfolded for us to see, appreciate and purchase. All along, we also learn and marvel about the craft. About how Ajrakh is derived from the Arabic word Azrakh, meaning blue, which therefore happens to be one of the primary colours of the craft; about how this artwork came into existence in the Indus Valley Civilisation around 2500 BC, and much more.

Ismail bhai’s studio is the first of our many stops, that over the next two days, left us marvelling at the sheer tradition, heritage and craftsmanship of Kutch.

Ismail Khatri's Ajrakh Studio, tucked in the bylanes of Ajrakhpur in Bhuj

The region of Kutch has about 46,000 square kilometres of land, but the astonishing variety of crafts found in this relatively small region is perhaps unmatched anywhere in the world. There’s block printing such as Ajrakh, Batik, and Bela, there are multiple types of weaving such as Kala cotton and Kharad, there’s knife work, pottery, lacquered wood work, leather art, metal bell art, wood carving, rogan painting and various styles of embroidery, to name just a few. With just a little over two days in hand, we hop from studio to studio and soak up as much as we can.

Kala Cotton, a strong and coarse organic fibre is indigenous to Kutch. Haresh bhai of Bhujodi, is a young, gifted artisan, who started weaving Rabari blankets with his father as a teenager. Now, a part of the ‘United Artisans of Kutch’, Haresh weaves the finest stoles, dupattas and saris out of Kala Cotton. We spend hours in his studio and home, watching him deftly demonstrate the technique and rhythm of warp and weft on the loom that brings the most delicate and traditional motifs of Kutch to life. Later, we walk towards open fields to discover long yarns of Kala Cotton stretched from pole to pole under a starry, moonlit night, left out to dry. Despite spending several hours with Haresh, we miss out on his other talent of folk songs, which he confesses keeps him company when he spends hours on the loom alone.

Haresh at his loom

No visit to Bhuj, Kutch, can be complete without stepping into the quarters and browsing through the stunning collection at the Living and Learning Design Centre (LLDC). Celebrating the rich and diverse traditional embroideries of Kutch, the sprawling nine-acre museum offers a glorious peek into the craft of communities such as Ahirs, Meghwad Marus, Sodhas, Rabaris and Mochis. LLDC is a pioneering effort of an initiative titled Shrujan that was started by Chanda Shroff in 1969. Shrujan recognised the exquisite hand embroidery practised by the women of the region and soon enabled drought-suffering Kutchi women to earn sustainable and dignified lives. Shrujan’s founder, fondly known to the villagers as Kaki, was honoured with the Rolex award for Enterprise in 2006.

The author at LLDC

Whilst every single artisan and craft that we encountered were both fantastic and applause worthy, perhaps the one that literally resonated with me the most was the art of handmade copper bells that we witnessed in the village of Nirona.

Making our way through the winding lanes of Nirona, we reached Luhar Husen’s home where the master artisan greeted us with a smile and a pair of twinkling eyes. Whilst the septuagenarian largely remained quiet, his son Luhar Faruk, explained how the family has been making copper bells for over seven generations, earning them the title of Luhar. As Faruk spoke about how each bell was jointless and had no welding or soldering, Husen quietly swung into action as he hammered discarded, lifeless pieces of scrap into beautiful, jointless copper bells that jingled to life in no time. He made his extraordinary work look like child’s play. Faruk explained how every bell once beaten into shape, was put in a brick kiln with a coat of paste and later got a wooden clapper attached to it. The final, magical touch was once again given by Husen, who crafted the sound of rain in one or the sound of chirping birds or ghungroos in another, just like that; just by his understanding of the metals and the many sounds he knew!

Luhar Husen hammering bells out of metals

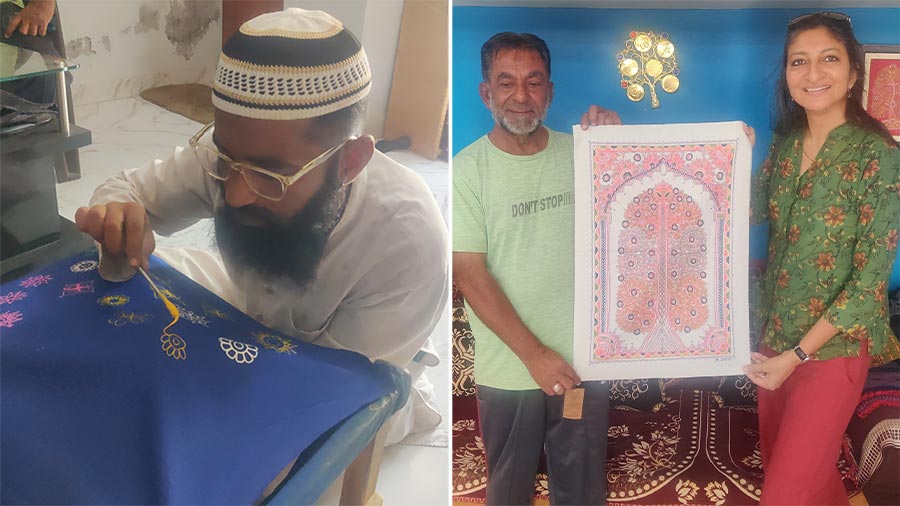

The art of Rogan may now be residing in the village of Nirona in Kutch, but it traces its roots back to Iran. National Award winner Abdul Gafur Khatri, or Gafur bhai as he is popularly known, has every reason to be smiling. From almost single handedly driving the resurgence of the once fading art form, he is also credited with imparting training to village children including girls so that they carry on the art. But what is Rogan? Remember Rogan Josh? Rogan comes from a Persian word and means ‘oil based.’ The oil in question is castor oil, which is first heated for long hours and then cast in cold water resulting in a sticky residue which gives the art form its eponymous name. A small stick is then dipped into this sticky substance and every stroke of colour (which is acquired through stone pigments) is then strung together on colourful pieces of cloth. A live demonstration helps us appreciate the immense concentration required. The result is that every piece of art is so fine that from a distance it almost looks like embroidery. Though an art form, Rogan uses a stick instead of a brush. One of its most popular motifs is that of the ‘Tree of Life’ which had been famously gifted to President Obama by PM Modi on one of his visits.

A Rogan art demonstration; holding up Gafur bhai’s Rogan work

Our final stop in Bhujodi, just before we make it in time to catch the train back to Ahmedabad from Bhuj is at Vankar Vishram Valji’s. Vankar Shyam ji, the patriarch’s prodigal son, is a much-revered name amongst the weavers and his colourfully dyed stories tell us why. Besides being an award-winning weaver, he has also shown great entrepreneurial zeal by involving his entire extended family and many others in the community, including women, on the loom. He uses his open courtyard to carry out the treatment of yarns, including preparation and dyeing whereas his well-stocked showroom sits at the far end of the courtyard. Shyam ji regales us with how all his fabric acquires colour via natural dyes. As an example, he explains how heaps of discarded marigold (genda) flowers of mandirs come to his workshop and are left out in the sun to dry, before they are treated to extract bright yellow and orange hues. Similarly, he explains how onion skins and other vegetable peels give them other interesting shades. The juice extracted from pomegranate peels is turned into a powder and finally used as a natural dye. Acacia (babool) seeds too are used cleverly.

(L-R) Vankar Shyam ji explains the dyeing process; spindles and yarns; a woman at the loom

Kutch can be dusty; its heat dry and unrelenting. Getting there a tad arduous and circling its lanes and by-lanes, somewhat exhausting. But if you are somebody who is interested in understanding the richness and deeply organic fabric of Indian craft, of how it has survived, thrived and wowed us for centuries, and of the sheer mastery and pride every community has over its lineage, Kutch is a must visit.

Two and half days are far from enough to explore Kutch and its multifarious crafts thoroughly. In fact, for the time we had at hand, we managed to cover some of its most prized studios and meet its most awarded artisans, thanks to the company of Niharika Joshi, who was involved in the archiving of Smritivan, the earthquake museum in Bhuj and therefore had inroads that navigated us to the right spots, effortlessly. We were also lucky to have managed to visit LLDC well beyond its usual timings, thanks to our wonderful homestay hosts at Kutch Courtyard, who organised our entry. Four-five days is the minimum recommendation, particularly if you intend to cover Rann, Dhola Vira and other nearby attractions.

The Kutch Courtyard

But be warned, for every stop in these villages lightens your wallet and purse before you know it! Hardly any tourist returns without succumbing to the sway of those gorgeous drapes that are unfurled at every shop and studio; by the many stoles, dupattas, saris or even yarns of unstitched fabric.

I should know. I have a copper bell hanging in my veranda, softly tinkling as it caresses the gentle November breeze that has blown all the way from Kutch to Calcutta.

Supriya Newar is an author, poet, music aficionado and communications consultant. Her travels take her to places where nature meets culture and stories unfold. She may be reached at connect@supriyanewar.com