Dalhousie Square, or what is now known as BBD Bagh, in Kolkata was once the political and commercial power centre of India. The area has many heritage structures, important for their history and architecture, such as the Lal Dighi and St John’s Church.

It was once the business address of all top British government and non-government organisations, starting from administrative buildings to police headquarters to major British banks and insurance companies and many more.

Young and restive youths of Bengal, who believed that a revolution drawing blood of the British was the only path to freedom, chose Dalhousie Square for many of their revolutionary activities. Two such daredevil acts that took place at Dalhousie Square are the Rodda Arms Heist of 1914 and expedition to Writers’ Buildings by three members of Bengal Volunteers in 1930.

The way a group of young Bengali revolutionaries managed to remove several cargo boxes of German Mauser pistols imported by a British arms dealer, Messrs Rodda & Company, on August 26, 1914, is jaw-dropping. The Old Customs House, where the present-day Reserve Bank of India building stands, and the office of Rodda & Company were both situated at Vansittart Row, a narrow passage going through the Standard Assurance Building, one of the most beautiful colonial edifices that Kolkata still has.

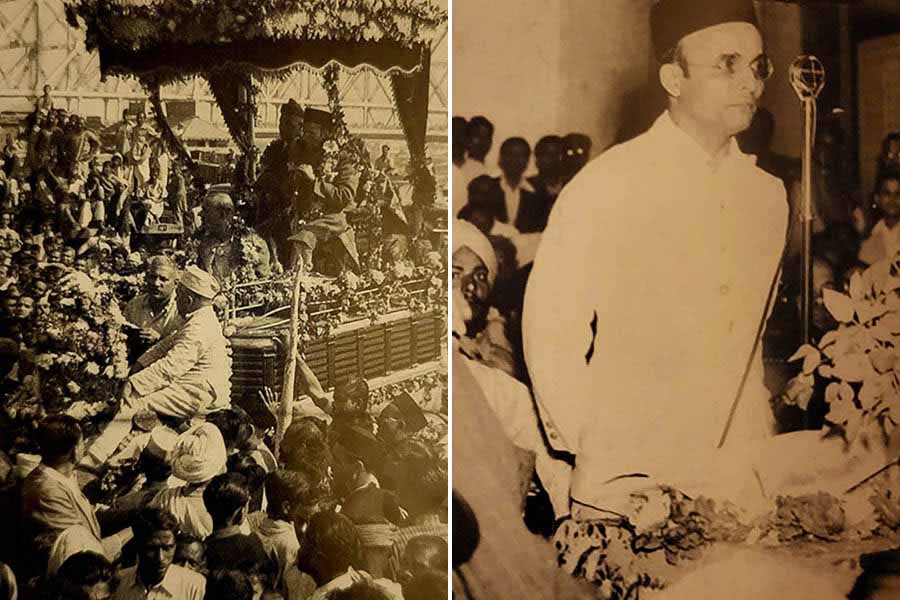

More than a decade later, on December 13, 1930, the country was rocked when Benoy, Badal and Dinesh stormed the Writers’ Buildings, the grandest edifice at Dalhousie Square, which then used to function as the administrative headquarters of the Bengal government, to kill a top British official in broad daylight. It is after them that BBD Bagh gets its name.

Sadly, most of our knowledge of the history and significance of Dalhousie Square ends with these two incidents. But there were many more such events for which Dalhousie Square deserves a place on the map of India’s freedom struggle.

The Charles Tegart murder attempt or Dalhousie Square bomb case

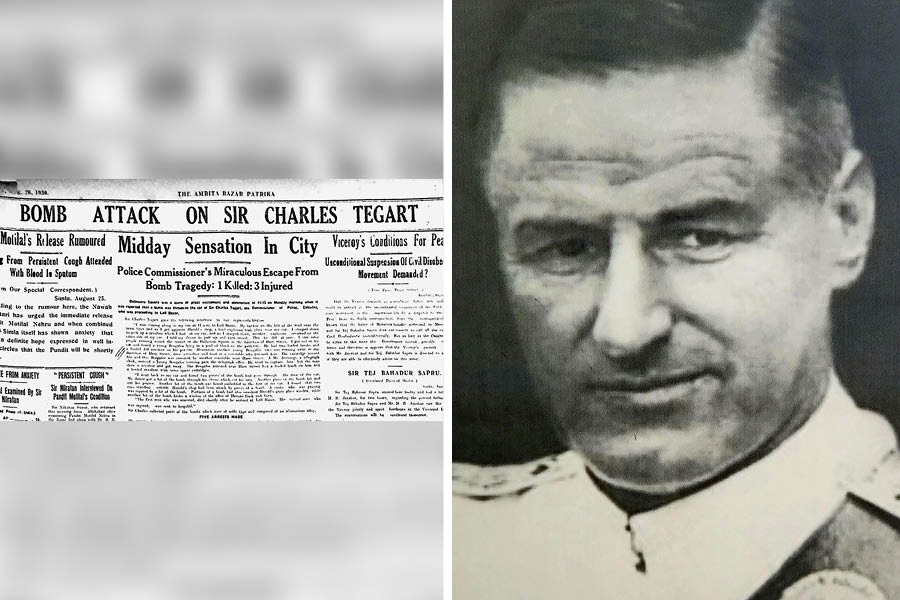

The Amrita Bazar Patrika report published on August 26, 1930, giving an account of the assassination attempt on Charles Augustus Tegart (also known as CAT to his foes) Archives

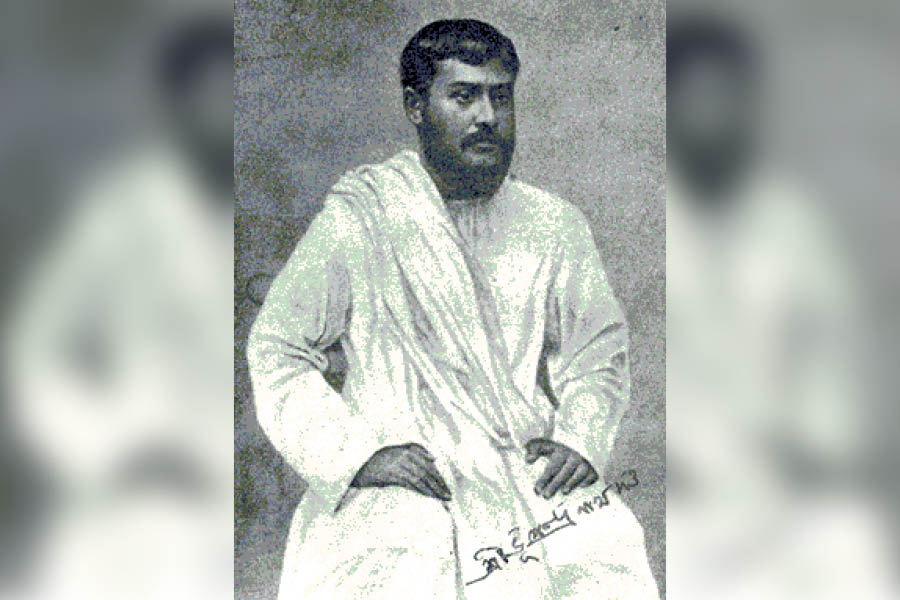

The most significant and now partly forgotten revolutionary act that Dalhousie Square had witnessed occurred on August 25, 1930, when a group of four young Bengali members of the Jugantar group carried out an assassination attempt on Charles Augustus Tegart (also known as CAT to his foes), the legendary police commissioner of Calcutta, who thanks to his extraordinary efficiency and brutal attitude, became a nightmare to Indian revolutionaries from 1906 to 1931.

For many years, multiple revolutionary groups of Bengal had been planning to kill Tegart but he managed to escape death every time, thanks to his luck and poor planning of the attackers.

On January 12, 1924, a young man named Gopinath Saha, in an attempt to kill Tegart at the Kyd Street-Park Street crossing, killed an innocent European named Ernest Day. Subsequently, Tegart survived a few more such deadly attacks.

In the middle of 1930, a new plan was drawn up to kill Tegart by hurling powerful bombs on his car and this was led by Dinesh Majumdar of Jugantar group who was also a student of law in Calcutta .

A team of four was formed with Dinesh himself, Anuja Charan Sengupta and Atul Sen — both from Senhati of Khulna — and one Sailen Neyogi.

On the morning of August 25, 1930, all four took their positions on the eastern side of Dalhousie Square near the Currency Building and near Dead Letter Office situated on either side of the road. They had done their homework on the colour, registration number and model of Tegart’s car. The plan was to hurl a bomb on the car and then resort to firing.

At 11.15am, Tegart was on his way to his office in Lalbazar. After crossing Great Eastern Hotel on Old Court House Street, his car was moving between Currency House and Messrs Harold’s Music store and was hardly six yards away from the tram tracks in front of St Andrew’s Church, when two assailants standing on the pavement of south and east junction of the park tossed the first bomb on the moving car. The bomb exploded on the tram tracks. It shattered the glass of Harold’s Music store and Thomas Cook & Sons showroom, injuring a coolie, two constables and riddled two parked cars.

The splinters of the bomb injured two passers-by, Mulchand, a chaprasi in Hastings Jute Mill of Rishra, and Tufani Dosad, a resident of Tikiapara of Howrah, as reported by Amrita Bazar Patrika the next day.

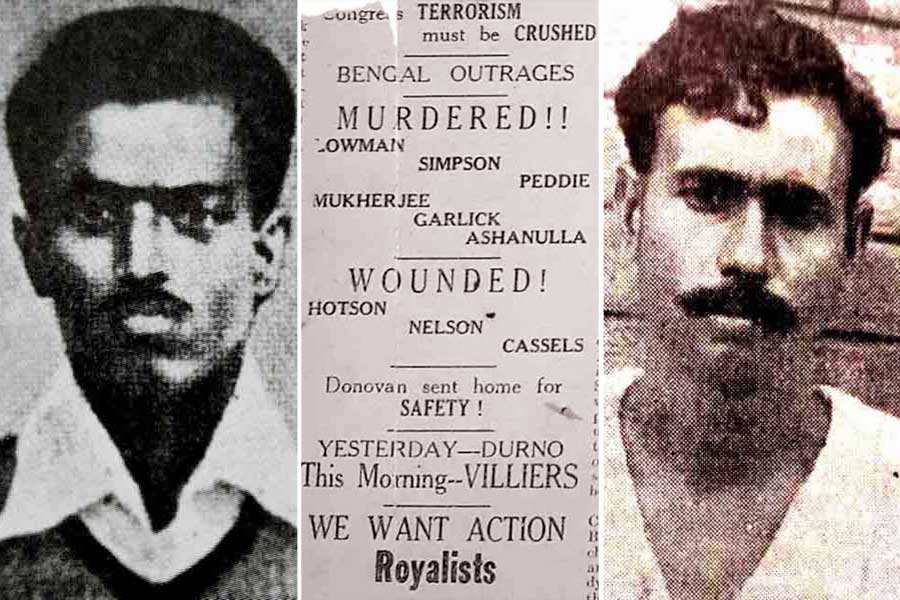

The Amrita Bazar Patrika headlines on August 26, 1930 morning and (left) Anuja Charan Sengupta and (right) Bimal Dasgupta Archives

Shocked at the sight of the massive explosion, Tegart — seated on the rear seat — took out his revolver and at that moment, another powerful bomb was charged and it almost hit his car. This powerful explosion damaged a wheel of Tegart’s car and a door very badly.

Smelling grave danger, Tegart ordered his driver to turn the car back and as the driver promptly did so, Tegart suddenly saw three Europeans, one constable and a few Indians chasing a blood-soaked man.

Tegart, alighting from his car with revolver in his hand, ran after the man and just a few yards from the erstwhile Dalhousie Institute building (now demolished to give way to Telephone Bhavan), the injured man slumped on the ground, bleeding profusely. He was Anuja Charan Sengupta. A bomb kept in his pocket had accidentally exploded, leaving him grievously injured. He was taken to Lalbazar by police and declared dead there. Police recovered two more metal bombs and a loaded .450 revolver from his body.

Meanwhile, Dinesh Chandra Majumdar, whose shirt was also stained with blood, was running towards Hare Street, where one Mr Jennings, a clerk working in the telegraph office, tried to capture him but he escaped by brandishing his gun. Finally, Dinesh was physically overpowered by another constable and arrested. Police recovered a bomb, a revolver and some cartridges from him. Atul and Sailen managed to blend in the crowd.

The unexploded bomb recovered from Anuja Charan Sengupta and (right) the damaged car door of Tegart, as displayed In the Calcutta Police Museum inside Alipore Jail Museum in the present day Photograph by the author

Immediately after this mayhem, Tegart personally visited Hare Street police station and lodged a case. He himself wrote the entire incident in the police records. He soon met reporters and narrated the assassination attempt on him. However, his version of the incident differed a little from the one reported by Amrita Bazar Patrika the next day. Tegart, in an interview, told The Statesman: “We have known for some time past that a recrudescence of terrorist activity was to be expected.”

Tegart was congratulated by the Viceroy of India, Governor of Bengal, members of Bengal Assembly, Calcutta Corporation and all big institutions from across the world. Alfred Watson, then editor of The Statesman, wrote a long editorial, blaming such senseless violence and praising Tegart as a great man.

(Clockwise from top left) St Andrew’s Church in Dalhousie Square was the place where the first bomb was hurled on Tegart on August 25, 1930; the Dead Letter Office, where a group of revolutionaries was waiting and Anuja Charan Sengupta’s body was found near the erstwhile Dalhousie Institute (now replaced with the Telephone Bhavan)

Calcutta police conducted large-scale raids in the next 24 hours and as soon as Dinesh was arrested from Calcutta Medical College, the entire conspiracy was cracked followed by many more arrests.

This case is known as the Dalhousie Square bombing case in the files of Calcutta police. In the Calcutta Police Museum inside Alipore Jail Museum, one can see the damaged car wheel and door of Tegart’s car and all arms recovered from Anuja Charan Sengupta and Dinesh Chandra Majumdar.

Attempt to kill president of European Association inside Gillander House

Bimal, knowing that he will not be able to leave Gillander House (in picture), came out of the room and tried to consume poison Archives

Just 14 months after the attack on Charles Tegart, Dalhousie Square was rocked by gunshots but this time, it was inside a famous business house.

The Bengal government amended a draconian law named Bengal Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1930, to break the backbone of terrorism executed against British and all Europeans.

The law aimed to counter those waging a war against the British monarch, enabling the local government to arrest and detain not only the person committing offences or about to commit them but also those who are the members of terrorist associations or help such associations.

The European Association, a body that voiced the interests of British rule in India, was a big supporter of this amended law. Thus, Bengal Volunteers decided to kill its president, E Villiers at his office in Dalhousie Square.

During that time, an organisation called ‘Royalist’ was formed by Europeans and Anglo-Indians, who ran a public campaign exposing the brutal and mindless killing of Bengali revolutionaries in Bengal. Villiers was a part of that as well.

E Villiers was the owner of M/s Villiers & Company. His office was housed at iconic Gillander House, the huge commercial building situated at 8 Clive Street.

Bimal Krishna Dasgupta, who killed Peddie, the district magistrate (DM) of Midnapore, on April 7, 1931, and managed to escape in the dark was assigned the task of killing Villiers. The date of action was decided as October 29, 1931.

Initially, it was decided that Dasgupta and Sengupta would both be part of the action. But at the last moment, Dasgupta took sole responsibility. He arrived dressed as an urban Muslim with a Turkish cap and clad in short pyjamas, coat and a leather bag in hand. He was sure that a Muslim entity wanting to meet a Britisher would not attract the attention of the security guards of the building.

Both Bimal and Benoy took the elevator to the third floor of Gillander House. There, Benoy before leaving, pointed to the office of Villiers to Bimal, who easily convinced the peon seated at the door to let him into Villiers’ room, where he was in a meeting with three members of Royalist Association — DW Mullock, AR Elliot-Lockhart and MacLauchlan. There was probably an Indian secretary of Villiers in the room. At the end of the meeting, Villiers and his team were having coffee and writing the minutes of the meeting when Bimal entered the room.

A surprised Villiers asked him the purpose of the visit in English and, in reply, Bimal took out both his guns and fired thrice.

Villiers was so fit a person that he, within fraction of a second, lunged beneath the table. Only a single bullet could graze his back, resulting in a small wound.

All others present in the room got so scared that they took guard. Bimal, knowing that he will not be able to leave Gillander House, came out of the room and tried to consume poison but someone threw a chair at him and he was quickly overpowered.

Villiers was lucky to be safe. He was taken to PG (now SSKM) Hospital, where he recovered fast. Within a few minutes, the top brass of Calcutta police, namely police commissioner (CP) L.H. Colon, deputy commissioner of police J.V.P. Janvrin and assistant CP Arther Robertson among others, arrived at the spot.

Bimal was arrested and taken to Lalbazar, where he was subjected to an unimaginable degree of physical torture for the next few days. Such was the brutality that seeing his gory face even the police commissioner ordered his immediate treatment. Dasgupta was sentenced to 10 years in the Andaman Cellular Jail.

“After Independence, Bimal Dasgupta went back to his hometown, Midnapore, and spent the rest of his life by running a small hotel. In the last stage of his life, he went blind but his memory stayed sharp,” said Arup Ray, who had interviewed him a few years before his death.

There are no memorials at Dalhousie Square to recall these revolutionary acts but they remain etched in the history of the Indian Freedom Struggle.