In the late years of the 1850s, two revolts had profound impact on the British rule over the Indian subcontinent. The first of these is the 1857 Uprising — which begun with the uprising by sepoys at the Barrackpore cantonment in Bengal and soon spread like wildfire across north India — resulting finally in transfer of power from the East India Company to the British Crown.

The second revolt, although more localised in scope, was no less significant in bringing about a major change in the administration of the land. Over time however, it has been relegated to the backgrounds of history. Today, I write about the times when the colours of the revolt turned blue.

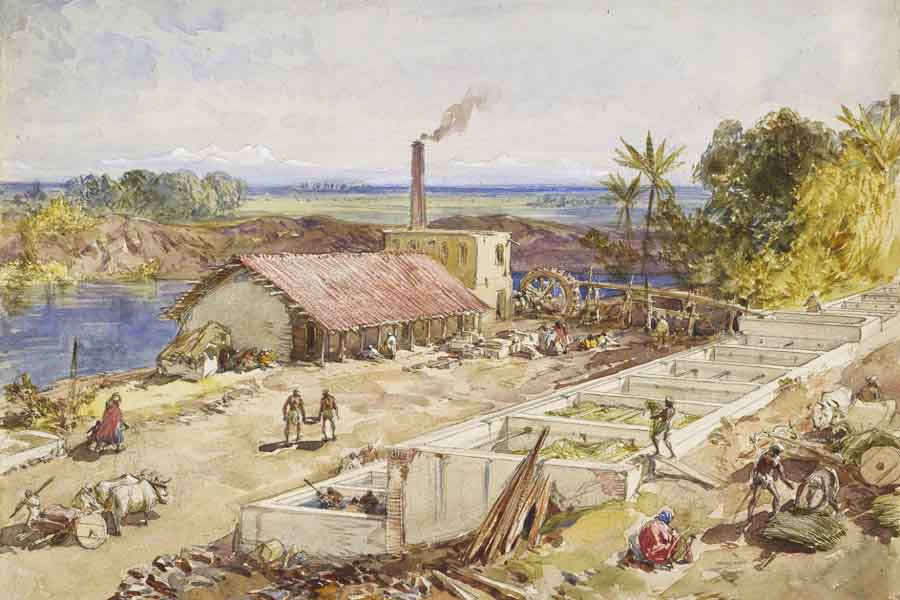

In 1777, a Frenchman by the name of Louis Bonnaud introduced the idea of indigo cultivation in Bengal setting up his plantations near the French stronghold of Chandernagore in Hooghly. The British soon realised the worth of this crop. Demand for blue dye in Europe was high and with the nawab of Bengal pliant to the Company, here was unlimited potential to grow the crop at the cheapest cost and earn great profits through importing. Soon, indigo plantations came up in a flurry across the south Bengal plains – stretching from Bankura in the west to Jessore in the east.

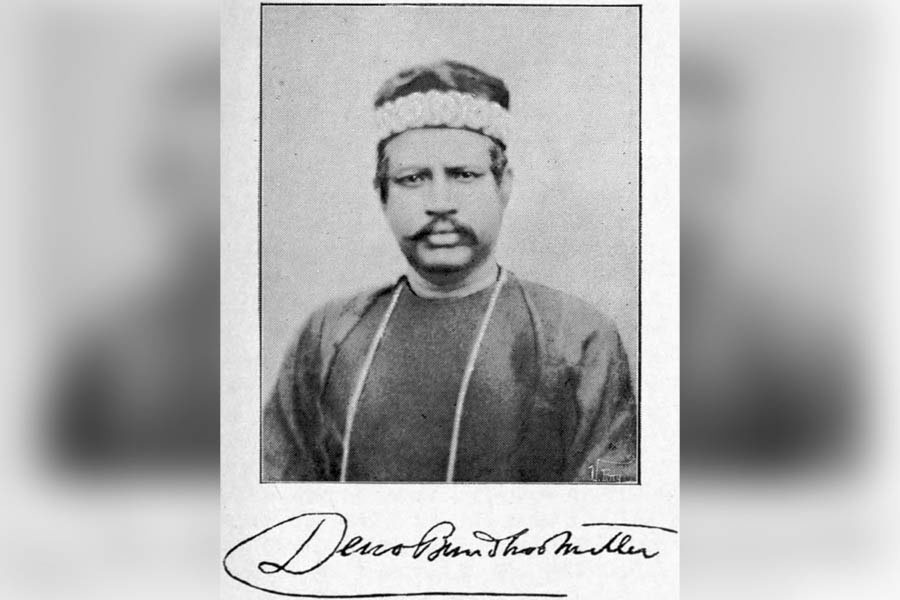

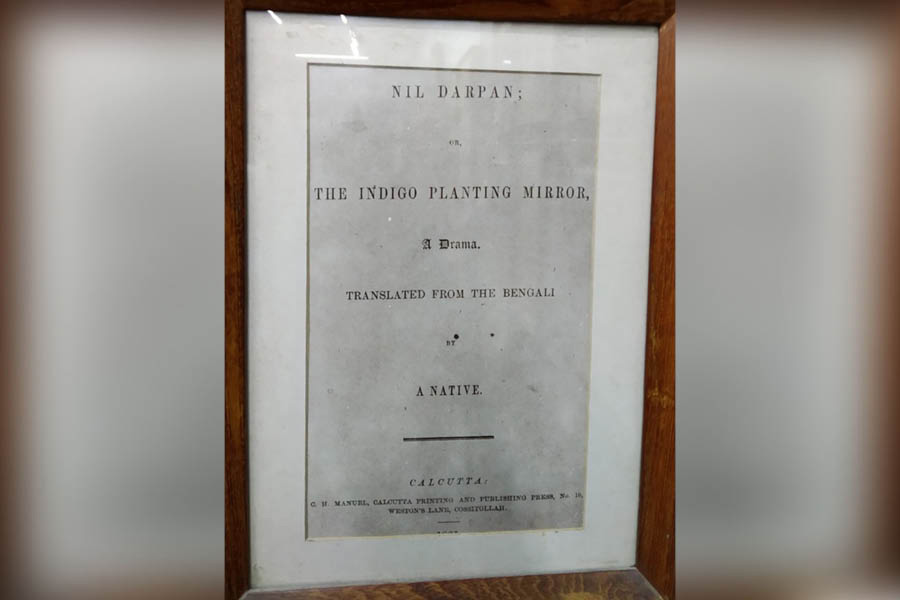

In 1860, Dinabandhu Mitra (in picture) wrote a play called Neel Darpan (Blue Mirror) on the indigo revolution.

However, one man’s meat is always another man’s poison. As the European planters minted money, the indigo cultivation came as bad news for poor farmers of Bengal. The farmers were persuaded to sow indigo instead of food crops on their land. If they did not agree, they were made to comply with brute force. Their fields were set to fire, their cattle were taken away and physical harm was threatened and sometimes acted upon. For carrying out the cultivation, the planter advanced an amount to the farmer which was in effect a loan – called dadon. The farmer was supposed to use that money to cover for the expenses of the cultivation. When the crop was harvested, the account was supposed to be settled. What seemed a fair arrangement on paper hid a dark secret.

The advance that was given carried a high rate of interest. Even with a full crop, he was usually unable to settle it. Moreover, failure of rains/pest attack etc. often damaged crops resulting in the farmer falling into a debt trap. The cunning planters used a devious trick to make the concept appealing to the farmers. The advances were typically given in October, just ahead of the Durga Puja celebrations. With the festive season up ahead, the idea of having hard cash at hand was irresistible to the poor farmers. Being largely illiterate, they could hardly comprehend the trap they were falling into. Year by year, the debt kept growing, shackling the poor native into invisible bondage. Many died leaving a huge burden of debt on their progenies. The planters formed political association in order to establish their hegemony over the countryside. There was no way out for the unfortunate agrarian. Any defiance was crushed in the most brutal manner.

The dam finally broke in 1859 in Krishnagar of Nadia district where the Biswas brothers – Bishnucharan and Digambar – led the local peasants in a violent uprising. Soon it spread across Birbhum, Burdwan, Murshidabad, Pabna, Khulna, Narail etc. Some planters, the most oppressive of the lot, were given a public trial and execution by hanging. Several indigo plantations were burned down to the ground. Apart from the Biswas brothers, Kader Molla of Pabna and Rafique Mondal of Malda were the other major leaders of the revolt. Although the zamindars (landlords) also earned the ire of the rebellious peasants, few of them like Ramratan Mullick of Narail actively supported the revolution.

The retribution from the ruler was fierce, swift and brutal. The British forces from Fort William and other barracks, often supported by the private militia of the indigo planters and the zamindars fell on the revolting peasants like a pack of wolves. Bishnu Biswas was arrested, given a mock trial and hanged publicly. One of the interesting aspects of this revolution was the mass involvement of women who often joined their menfolk in the fights with kitchen utensils as weapons. The other standout feature was the adoption of non-violent means of protest in some places.

‘Neel Darpan’ was translated into English reportedly by Michael Madhusudan Dutt* and was published by Rev. James Long, an English missionary.

The lieutenant-governor of Bengal province, JP Grant, while on an inspection trip to eastern Bengal, was startled by the sight of thousands of villagers lining a riverbank praying for a government order banning indigo cultivation. A large chunk of the group was women and children. Similar instances were reported from other places as well. The indigo revolution in Bengal may well have witnessed the first application of non-violent protests as a tool of dealing with oppression, something that would become the main feature of the country’s Independence movement in the 20th century.

Although the revolution was brutally crushed, its after-effects were reverberating. LG Grant was much moved by the sight that had greeted him on his trip. The waves of the movement reached Calcutta. Harish Chandra Mukherjee, a prominent journalist of the time, had written several articles in the Hindoo Patriot right from its inception in 1853, criticising the brutal indigo cultivation tactics. In 1860, Dinabandhu Mitra wrote a play called Neel Darpan (Blue Mirror) on the indigo revolution. It was translated into English reportedly by Michael Madhusudan Dutt* and was published by Rev. James Long, an English missionary. The English translation reached the British Isles where it led to a collective shock at depictions of the inhuman torture of the poor farmers. The local administration was furious and imprisoned Rev. Long and also imposed a fine of Rupees 1000 on him. Meanwhile, Nawab Abdul Latif, a prominent educator of the time who had good relations with the British regime lobbied endlessly for putting an end to the horrors of the indigo cultivation.

With pressure mounting from multiple sides, the government was forced to form the Indigo Commission in 1860 with two members from the government, one from the European planters, one from the Christian missionaries and one representative of native zamindars. After interviewing more than 100 people across farmers, planters, zamindars, missionaries, officials etc. the commission submitted its report in August 1860. The report made it abundantly clear that the indigo cultivation process was inherently exploitative in nature. The government had egg on its face when Ashley Eden, the magistrate of Barasat testified to the commission that not a single indigo cultivator did so out of ‘free agency’ but did it from force and oppression. EWL Tower, the magistrate of Faridpore, was quoted saying: “Not a chest of Indigo reached England without being stained with human blood.”

Basis the report of the commission, the government of India promulgated the Indigo Act in 1862 to regulate the cultivation process and reduce the oppression of the poor farmers by the planters. However, on the ground the situation changed only marginally. In some years’ time, the invention of synthetic indigo and the resultant redundancy of natural indigo finally ended the torture and oppression that peasants across Bengal province were subjected to for more than a century.

The indigo revolt in Bengal is an important chapter of India. Sadly though, it has been nearly forgotten and reduced to mere footnotes in the pages of history.

*The identity of the translator of Neel Darpan was never officially known. Rev. James Long refused to reveal it. But it was widely believed that the translation was done by Michael Madhusudan Dutt