The irony of Elite Cinema is that in a city of 206 million square metres, it was destroyed not more than 30 metres from the municipal institution responsible to protect it.

Could it have been saved? In a sense no, considering that the end use application of that property had become irrelevant. How many readers of this article would have been willing to drive five or 10 km, ferret parking 200 metres away, watch a film and drive home through congested traffic? Besides, leaving an asset of this nature fallow only because its facade resembled art deco would have been too much to expect from an owner seeking to sweat his Return on Capital Employed.

But, m’lord, there is a defence as to how Elite’s front — not the entire property — could at least have been saved. One, the art deco facade could have been retained and the new development built behind. This was done at the Mackinnon Mackenzie building (however mismatched the new glass box construction behind appears) in BBD Bagh; it was done with the Metro Cinema facade in Esplanade (deconstructed only to be reconstructed around the original design).

While Elite Cinema’s end use application had become irrelevant, an argument can be made that its front facade could have been preserved while continuing new construction behind

The demolition of Elite Cinema was shocking for its speed and insensitivity. It wasn’t done conventionally brick by brick; it was bulldozed in the dark of the night. What should have taken a few days of daylight hours was achieved in a single night. The shock was not limited to this. No heritage group issued a protest statement or turned up at site for sit-in protest; most Whatsapped the demolition media article as a form of verbal maatam.

Time warp in a cinema hall

Just 50 metres from one of south Kolkata’s arterial roads, Indira cinema is a fine example of art deco design that made its way to Calcutta in the early 1900s

Following this concrete cremation, I visited Indira Cinema in Bhowanipore. Part out of admiration, part out of curiosity. Indira is unique among Kolkata’s cinema houses. Its facade is not conventionally rectangular; it is circular. It sits on prime property. It is 50m from one of the busiest south Kolkata arteries. Its film screen has been shut for years.

I was not being unreasonably intrusive when I asked: will Indira endure? Before this question could be answered, let me describe what I chanced upon. A time freeze. One of the most romantic insides across any cinema house in Kolkata. Black and white chequered tiles, monochrome lobby cards of films screened through the 1960s and ’70s. The warm yellow of globe-shaped light shades. The netted seats of wooden chairs. The rusting projector. The song books framed in the corridor. Film spools. The only thing missing, understandably, was a calendar marked ‘1968’.

Inside Indira, one enters a time warp with posters, memorabilia and remaining articles and artefacts from the theatre’s mid-1900s heyday

I wasn’t merely stepping into a disused cinema hall; I was tiptoeing into a nostalgic postmodernism Cinema Paradiso where once upon a time the first bell would be followed by a shuffle of hurried feet, the swing of heavy wooden doors, the blast of stale cigarette-heavy air-conditioning, the crackled static of rotating film and the projector shafting grainy white into the black of the hall.

A prized possession

When I went, I half-expected a canny number-cruncher with a half-drafted Memorandum of Understanding about an impending property sale. I found an owner (Rajendra Bagaria) soaked in the nostalgia of the Uttams and Suchitras instead. I half-expected to find an accountant seeking to dispose of the artefacts from Indira’s cinematic past by salvage value (‘kilo ke hisab se’); I found a promoter turned aggregator of whatever he can find of cinematic value from dealers. I half-expected an owner complaining how the world is treating conventional cinematic formats; I chanced upon an entrepreneur seeking to find a solution.

Owner Rajendra Bagaria has been on a quest to restore and refurbish existing structures and artefacts inside the old cinema

This didn’t make sense. Even if you apply a conservative six per cent return on employed capital, the investment in the cinema house was generating virtually no return; this ownership was not just a losing proposition, it was a hopelessly losing proposition.

Bagaria replied with a word one would not associate with people of his social or economic background: “Paagalpan”. He elaborated: “It was the shauk of owning a property like this. After I had bought it, I fell in love with it. By the grace of god, one is financially comfortable, so squeezing the last RoCE drop from this acquisition has become irrelevant. More so, my children view this with pride. not with the conventional ‘Why don’t we shift this off our books at a profit?’ The family will not bardasht karo if anyone even uses a hammer on Indira Cinema. Besides, our dal roti is secured. Why be greedy for more?”

That vernacular word for madness was perhaps used responsibly. Bagaria says he saw his role as fighting back for every single chair or table or door that came with the cinema house. He repaired them all. He merged some to make composite wholes again. The missing original wood and glass of a ventilation was plugged with a replacement from a pre-used furniture dealer. Everything just had to look 1950.

Bagaria has been repairing interiors and sourcing memorabilia like old film posters with the idea of turning Indira in a cinema house or a museum

For a man whose workplace stopped functioning some years ago, Bagaria goes there punctually to work each day. Planning a turnaround. Taking stock of what he has. Buying film memorabilia off the net. Tracking down which Okhla film poster dealer will give him a Mughal-E-Azam wall poster. Checking where he might be able to source Uttam-Suchitra film lobby cards.

Bagaria’s cinema house may or may not materialise but what keeps him going is the prospect of a museum instead. “I am open to collecting all kinds of film memorabilia — lobby cards, autograph books, old film reels, song books, gramophone records and film cans — so that one may recreate some magic of what once existed. If you are looking for a word that you hang this conversation on, then that word would be pride. We all wish to leave behind something by which we would be remembered. I hope to be remembered as the man who protected Indira Cinema from being destroyed.”

From Uttam Kumar film lobby cards and photos to old cinema theatre equipment — there’s a treasure trove inside Indira

Architectural gem

Indira Cinema is important for us for another reason. The façade and insides are uniquely art deco, an abbreviated form of the French arts décoratifs (decorative arts),a style of visual arts, architecture, and product design, that first appeared in Paris in the 1910s (just before World War I), and grew across the United States and Europe into the early 1930s.

Art deco was distinctive because it wasn’t just one thing; it represented the convergence of the bold geometry of Cubism and the Vienna Secession; its bright colours were drawn from Fauvism and Ballets Russes; its furniture craftsmanship came from the Louis XVI and Louis Philippe I eras; its exotic art styles were sourced from China, Japan, India, Persia, ancient Egypt and Maya (Mesoamerica).

The patterned and chequered tiles inside Indira cinema are one of its design highlights

Art deco was catalysed by humankind’s need to embrace the new following the First World War. Its sleek lines and geometric shapes were a reflection of progress with the design essentials of machine-made objects — simplicity, planarity, symmetry and a consistent repetition of elements. It was characterised by an emphasis on luxury, opulence, and decorative details — bold geometric shapes, rich colours, and ornate patterns.

This art deco was not confined to a small experimental pocket and window; it reflected the design flavour of more than two decades, influencing the way bridges, structures (skyscrapers to cinemas), ships, trains, vehicles, furniture, and everyday objects were designed. So art deco is not just a reference to an architectural influence (even as the Empire State Building, Chrysler Building, and other prominent US structures are instances of this style); it is a comprehensive gharana that extended across forms and pieces. The result is that whenever anything is considered art deco in influence, it is bucketed notches higher into an exclusive club.

The orgasm of this design movement was the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris in 1925. The 55-acre event sponsored by the French government comprised 15,000 exhibitors from 20 countries and was visited by 16 million people during just seven months. The event would have been like any other but for the fact that the exhibition insisted on all displayed work being modern.

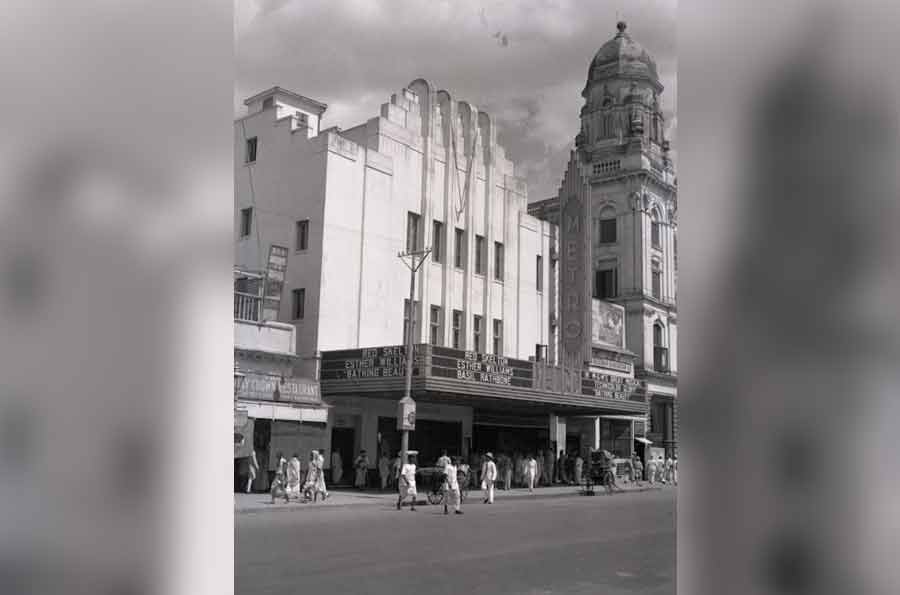

Many old Kolkata cinemas like New Empire and the signage of Metro Cinema (in picture) had art deco elements Bond Photography Library/Digital South Asia Library

The art deco ripple extended to Calcutta, the second city of the British Empire during the first quarter of the last century. By virtue of its position, Calcutta attracted new money and new architecture styles (read art deco). A number of properties in central Calcutta, Southern Avenue and the Lake Market area are art deco. The prominent English language screening cinema houses of the past — New Empire had a Greek goddess perched on top and checked floors; Metro’s external signage — were art deco. So was Indira Cinema, launched for the public in 1945.

The tragedy is not just that Elite was martyred (‘shaheed’); the tragedy is that some visible portions could have been saved while the insides could have been adapted for reuse. The more I mourn the loss of Elite’s frontage, the more I need to thank Bagaria. The man concedes that this cinema business will never repay adequately, but some battles he would rather fight for pride over profit.

One of these days I intend to go back to Indira Cinema. With a proposal. That as a gesture of gratitude for Bagaria’s commitment to heritage, I would be willing to illuminate the facade of his Indira Cinema property at no cost to him. Only to say thank you. Only so that those driving past SP Mukherjee may be compelled to turn and notice. Only so that in this lone man’s fight to protect every brick of this art deco showpiece, he found in his city a humzubaan.

He might even say yes.