Architecture is a representation of a city’s past as well as its future. In theory, old buildings, which have inevitably become difficult to use and maintain with age, need to be pulled down. Yet, a nobler impulse might often remind us of the historical and emotive value of certain old buildings and sites, in which case the imaginative reuse of such buildings can give them a new lease of life.

Several colonial architectural styles once dotted the streets of Calcutta, it being the capital of British India until 1911. From the Gothic and Neoclassical to the Art Deco style of the early 20th century, a profusion of fluted columns, sweeping flights of stairs, arches, pediments and chevrons could be found everywhere, from Esplanade and Dalhousie Square to Central Avenue and Theatre Road.

In a sudden burst of nationalist feeling & anti-colonial sentiment after Independence, many buildings were pulled down in important locations to make way for ‘modern’ buildings in the 1950 and ’60s.

The ornamented sweeping canvasses of colonial buildings were swept away by the pressures of creating residences, shopping centres and offices for a rapidly expanding city.

With time, the names of roads were changed and buildings were razed to make way for large glass-fronted multi-storied buildings. These have nothing of the ornate majesty and finesse of their predecessors, but look like matchboxes or glass shelves. The ornamented sweeping canvasses of colonial buildings were swept away by the pressures of creating residences, shopping centres and offices for a rapidly expanding city.

Colonial buildings which survive today are found mostly in properties owned by the government and are used variously as offices, memorials and residences. We stumble past them every day while they stand firm, staid and unnoticed. There are a few that have been spared the eagle eyes of real estate developers: the Dead Letter Office in the central business district, the Treasury Building opposite it, the Governor’s residence or Raj Bhavan, the High Court, the Tropical Medicine building near the Medical College, St. Andrews Church and other such estates belonging to the Church.

Markers of a shared, lived past

Besides these, existing only in a vague, faraway vacuum, are the ones owned by the police. Over recent decades, there has been a public awakening to the historical significance of such buildings, as markers of a shared, lived past that one cannot (and should not) try to shed. Accompanying this, ideas about conservation and restoration have pervaded the public consciousness. No longer is it the stuff of esoteric academic reading or architectural magazines from abroad. Old buildings have been classified as heritage properties, maintained and restored, and have on the whole, gradually been brought into the fabric of mainstream civil society. Increasing numbers of people are coming forward to protect Calcutta’s architectural history, while in the ranks of the police and administrative services there is great pride and excitement about these structures. A steady stream of social media posts and magazine articles revisiting the grandeur of these buildings shows how these buildings inspire and enliven even today. Even 10 years ago, some of these remarkable precincts were in shadow – paint-worn, plaster-peeled, damp, broken and layered with dust.

I can only speak for the police. Here I detail the stories of four selected iconic buildings owned by the police that came to be saved and how they were restored. All of them won awards by INTACH and acknowledged by the Heritage Commission for their restoration. There were other such buildings that were restored, the stories of which are kept aside for another day.

Dalanda House

Another view of Dalanda House. Along with the Police Training School, it also houses the Police Dog Squad

The Police Training School, off the Race Course on Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Road, has immense interest for those who love the past. The building, whose boundary can be seen from the road, is known as Dalanda House. The name originates in the word dullundah, which was one of the 55 villages acquired by the East India Company in 1758. In 1847, the nascent city’s biggest lunatic asylum was established here after shifting the old one from Russapagla, near what came to be known as Russa Road. In 1906, Dalanda House was given over to the Stamp & Stationery Department of the Government of India.

In 1914, after eight years of persuasion, Sir Frederick Halliday, the Commissioner of Police, Calcutta, succeeded in establishing the Police Training School here and overcame the rather cumbersome process of sending police recruits to Bhagalpur for training. With time, Dalanda House became infamous because Charles Tegart used it as an interrogation centre for freedom fighters of Bengal. Perhaps, some of the stigma attached to the property was also due to its architectural design, which seemed to have shades of a prison house about it. The house stood in the middle, surrounded by a circular structure resembling the panopticon envisioned by Jeremy Bentham.

Such a style was used in prisons and hospitals, where the cells along the external wall with a central rotunda allowed inmates to be watched without their knowledge. Dalanda House replicated this possibly because of its use as a lunatic asylum. For years, the house and its grounds were kept up in an uninformed, slap-dash way without any lasting attempt at rescuing it from the ravages of time. In 2014, Dalanda House was thoroughly overhauled, its gatehouses repaired and painted, the buildings inside revamped and refurbished. Today it is not only the centre for the city’s police training but also houses the Police Dog Squad.

Almond House

Almond House houses the Sealdah Traffic Guard, on Canal Street

Another building which has survived obliteration is one that houses the Sealdah Traffic Guard on Canal Street. Originally called Almond House, records show that it was built in the last years of the 19th century. A succession of owners included CH Smith, CJ Disscut, Sir Abdul Halim Ghuznavi, the latter being the zamindar of Delduar, in Mymensingh, as well as the chairman of the Tangail Municipality. Sir Abdul was active in contemporary politics. In 1905 he moved a resolution opposing the Partition of Bengal in a session of the Indian National Congress at Benaras. To popularise Swadeshi goods, he started the United Bengal Company and the Bengal Hosiery Company. He was a member of the Indian Legislative Assembly in 1927 and was a delegate to all the three Round Table Conferences. In 1935, he was appointed as the Sheriff of Calcutta. Sir Abdul’s house had a rich collection of rare books and documents and was also used as a venue for socio-political meetings including several Swarajya Party meetings. In time, the house became derelict, its trustees could no longer maintain it.

Deliverance came in August 1970 when this 28 cottah property was acquired by the Commissioner of Police, Calcutta, for the use of the Enforcement Branch. In 1976, the Sealdah Traffic Guard was established here and in time the building became so derelict that there was a move to demolish it. Fortunately, in 2014, at about the same time as the repairs of Dalanda House was going on, finer minds committed to the conservation of police heritage buildings revoked the decision and got it restored. The Sealdah Traffic Guard stands in stately splendour today, a beautiful double-storied structure in the Neoclassical style, complete with a portico, segmented arched openings and overhanging balconies with decorative balusters.

Limelight

Limelight, on Ripon Street, exists as a library-cum-museum complex, dedicated to the citizens of the city

A similar interest in the preservation of historic architecture led to the renewal of another sumptuous structure on Ripon Street. This was a double storied and magnificently built house, which belonged to the Maharaja of Nadia, Kshitish Chandra Roy, who named it Nadia House. In 1912, the house was purchased by Surendra Nath Motilal of Muchipara for his daughter Sarajubala Devi, who married the ‘Borokumar’ of the Bhowal Estate of Dhaka. In 1926, the building was remodelled and the Maharani of Bhowal owned it till 1948. Mejokumar, also known as Ramendra Narayan Roy of the ‘Sanyasi Raja’ fame, stayed here between 1924 and 1929 and fought his legal battles in the Calcutta High Court and the Privy Council.

During World War II, the British Government of India requisitioned the premises for the Allied troops and later handed it over to the Commissioner of Police, Calcutta who formally acquired it in 1948. By 2004 the building, now old and ramshackle, was being considered for demolition. In 2013, the Kolkata Police Housing & Infrastructure Development Corporation Ltd restored the historical building, re-designed the landscape of the premises and saved it from oblivion. It was renamed Limelight and exists as a library-cum-museum complex, dedicated to the citizens of the city.

Manasseh Meyer

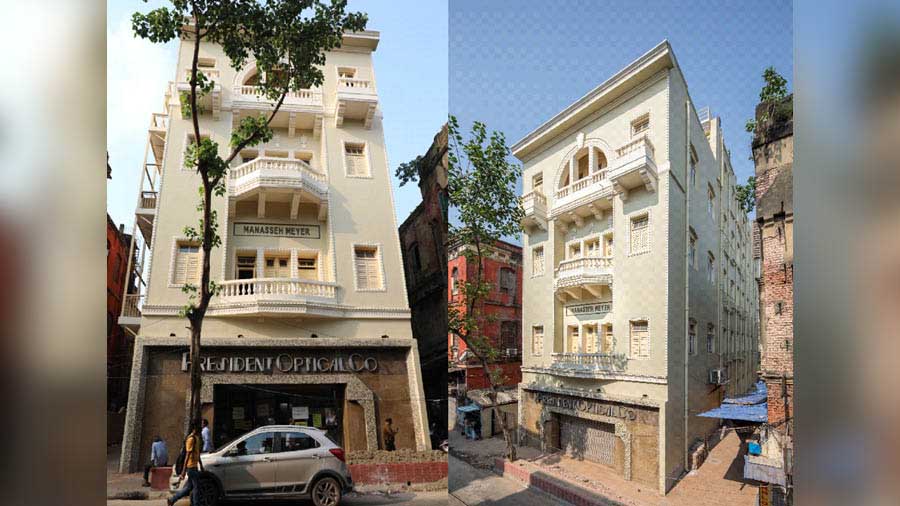

Manasseh Meyer on Bowbazar Street

Manasseh Meyer is another mansion that many passing through the busy Bowbazar Street (earlier known as the Avenue to the Eastward) noticed for decades crumbling down. It was built by a Bagdadi Jewish businessman and philanthropist, Sir Manasseh Meyer, in 1911 for commercial use. He was a reputed businessman having interests in Calcutta as well as in Singapore. During World War II, several families of police sergeants were moved here as part of the Dispersal Scheme after evacuating them from Lalbazar as a precautionary policy against Japanese air strikes. Subsequently the building was acquired by Calcutta Police.

With time, the building became dilapidated and was abandoned. In 2021, the mansion was restored and was put to use as the annexe of Lalbazar.

An important reminder of a definite moment in the nation’s past

In an era of globalisation, cultural cross-fertilisation has an important resonance. The buildings described above are examples of European-style architecture from India in the 19th century and exist as an important reminder of a definite moment in the nation’s past. The aim of restoration is to counter the notion of development as an aggressive demolition of old buildings without any reference to their historic value. Today’s Kolkata has evolved from Calcutta, a city where anybody who wanted to be somebody once flocked to. If these old buildings, which represent the international cosmopolitanism that has always been the hallmark of Calcutta, are brutally erased then what is to stop our city from becoming a provincial defeat in the global map of architectural evolution?

There are scores of beautiful buildings in the city which are in danger of being summarily pulled down and replaced by some hapless shard of glass. Perhaps it is time to re-energise, reinterpret, rehabilitate and restore them.

The author is former commissioner of police, Kolkata.