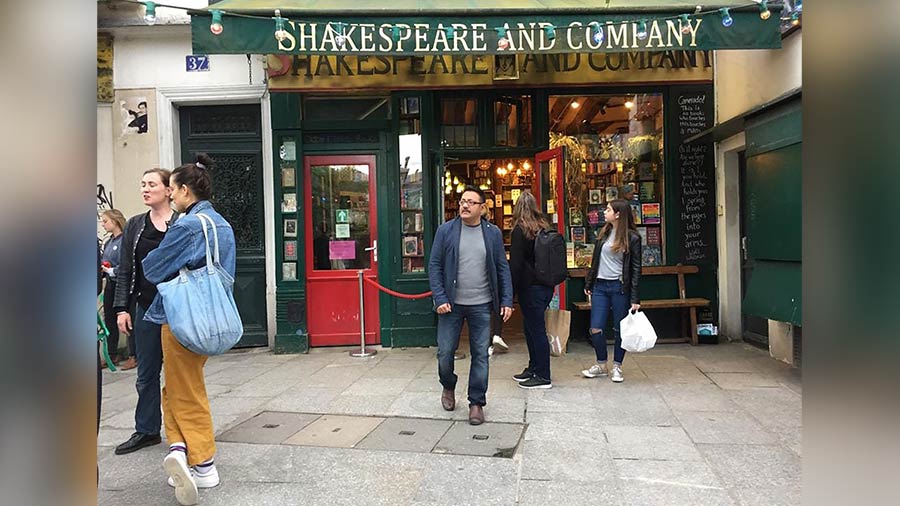

It is a lazy Sunday morning in Paris. A quiet stroll through Rue de la Bûcherie has led me to Shakespeare and Company, arguably the most famous independent bookstore in the world.

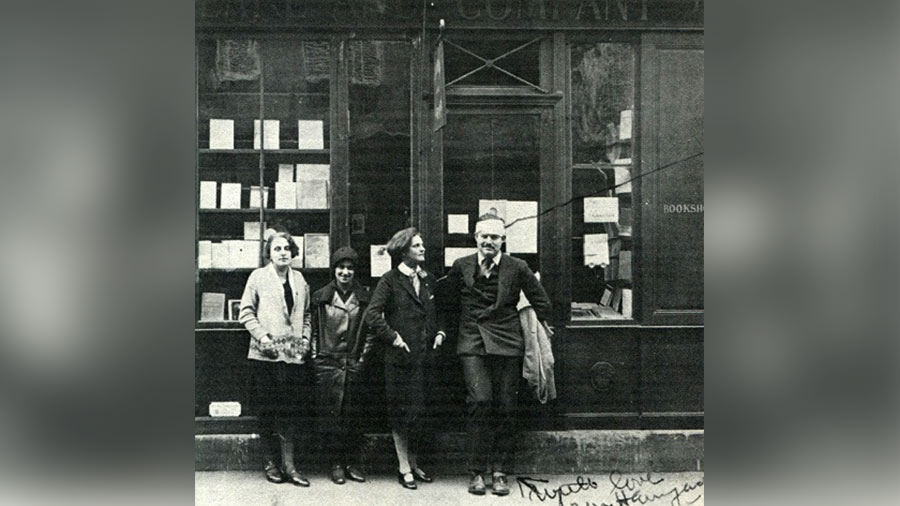

The literary institution on Paris’s Left Bank began its journey in 1919 with American expat Sylvia Beach, who started a small lending library at nearby street Rue Dupuytren, before she moved it to larger premises about two minutes away in Rue l’Odeon in 1922. The current establishment opposite Notre-Dame is a continuation and homage to Beach’s, which shut down in 1941.

Today’s Shakespeare and Company is housed in a 17th-century building. The faint smell of mildew hangs in the air, even as the delightful aroma of freshly-roasted coffee — nutty and caramel — wafts up from the cafe below. A few visitors silently negotiate their way through the small room filled with books, stacked in row after row of archaic shelves built deep into the walls.

In its earliest years, Shakespeare and Company (or Shakespeare & Co. as it is often called) was only a humble assortment of literary magazines and books, half bookstore and half lending library, housing the contemporary works of T.S. Eliot, James Joyce and Ezra Pound. The informality set the tone for an atmosphere that would soon turn Shakespeare and Company into a meeting place for avant-garde writers such as Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald and James Joyce. When Britain and the United States declared Ulysses indecent, Beach came forward to publish James Joyce’s magnum opus in its complete form for the first time. The publication brought global fame to the author and Shakespeare & Co., triggering a surge of innovative publishing of the works of the regulars of the bookstore. It also attracted some of the century’s most well-known female authors including Djuna Barnes, Gertrude Stein, Janet Flanner, Kay Boyle, and Mina Loy.

The first location of Shakespeare and Company Courtesy shakespeareandcompany.com

Over the next few decades, Shakespeare and Company became the regular haunt of the famous and soon-to-be-famous. Hemingway came over for joint book readings with Stephen Spender or a sparring session with Ezra Pound. Surrealists like Man Ray defended their movement against its detractors over coffee. Literary magazines also used the bookshop as their editorial address. And along the way, Sylvia Beach would play the mother hen to the slew of writers. Ernest Hemingway would later write of her in A Moveable Feast, a delectable memoir of his Paris days, saying, “No one I ever knew was nicer to me.”

The summer of 1941 changed all of this. The bookstore closed its shutters in Nazi-occupied Paris. The story goes that Sylvia Beach refused to sell the last copy of Joyce’s Finnegans Wake to a German officer, who then threatened to come back and confiscate her books. She immediately packed up her books and closed the bookstore. After the war was over, Hemingway would try to reopen Stratford-on-Odeon (as the bookstore was lovingly nicknamed), but it did not work out.

Ten years later in 1951, George Whitman, an American ex-serviceman, would open a bookstore named Le Mistral on Rue de la Bucherie. In a few years, much like Shakespeare and Company, it would become a hotbed for bohemian Parisians and the celebrated haunt of Beat Generation writers like Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs and Gregory Corso. Burroughs made the bookshop his base to research portions of his cult novel Naked Lunch using Whitman’s collection of medical textbooks.

Whitman wanted to continue from where Beach had left. A delighted Sylvia named Whitman her ‘spiritual successor’ and passed on the rights to the name ‘Shakespeare and Company’ to the young American. In 1964, two years after Sylvia’s death and on the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth, Whitman renamed Le Mistral as Shakespeare and Company. He called his bookstore “a novel in three words.”

While Beach offered mentorship, access to free books, and sometimes financial assistance to young, brilliant and often cash-strapped literary aspirants of the interwar years, Whitman took it one step ahead. According to him, Shakespeare & Co. was “a socialist utopia masquerading as a bookshop,” and he created a haven for young, struggling writers and creatives from across the globe. They could find a home here and crash on the slim bedsteads tucked between the shelves and alcoves. In return, they put in a few hours of work in assisting the store’s daily affairs, with the clause that they would have to read one book a day and write a one-page autobiography for the shop's archives. Whitman referred them as ‘tumbleweeds’ that "blow in and out on the winds of chance."

It’s a legacy that Whitman’s daughter Sylvia (who was named after the original owner) and her husband David have lovingly continued after George’s death in 2011. It is estimated that around 30,000 ‘tumbleweeds’ have been hosted in this Left Bank establishment till date.

I wind my way through the rooms, charming in their clutter with musty stacks and rickety old chairs, I bump into Francis. The young Spaniard is a ‘tumbleweed’ who has made the store his base for a couple of weeks. He wants to start a novella from here. He guides me to one of the store’s hidden gems — a collection of first editions from the 1920s and 1930s, before he goes back to the sales counter for his shift.

I forage some more through the shelves that stock a mix of recent works of Anglo-American writing, Paris-themed journals and antiquarian literary treasures. It is a treasure hunt of sorts and I bagged a couple of old copies of The Paris Review and a 1979 edition of Little Birds by Anais Nin. As I leave with my day’s haul, I catch sight of a large printed message pinned on the wall: ‘Be not inhospitable to strangers, lest they be angels in disguise.0’

I wind my way down the wooden stairs, past a well-worn piano, and out into the summer morning that has turned brighter and breezier.

Sugato Mukherjee has bylines in BBC, The Globe and Mail, National Geographic Traveller, Al Jazeera, Deutsche Welle and several inflight magazines. His coffee table book on Ladakh has received critical acclaim. Sugato's work on the sulphur miners of East Java was awarded distinctions by UNESCO. He writes on travel, culture, environment and food.