“Men wanted for hazardous journey, low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness, Safe return doubtful, Honour and Recognition in event of success.”

E. Shackleton; 4, Burlington Street.

Thus went the advertisement published in London newspapers by Antarctica expedition legend Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton, ahead of yet another journey to the world’s southernmost continent.

It was 1914 and Shackleton was getting impatient again. His previous expedition in 1907-09 aboard the Nimrod had made him famous in England. Then 33 years old, the Anglo-Irish explorer had set off on the three-masted, 40-year-old wooden sealing and whaling vessel with the aim of reaching the South Pole, which no one had done yet. Unfortunately, the Nimrod Expedition would be a case of so near yet so far. Shackleton had to return about 98 nautical miles from the Pole, as his men did not have the energy and the strength to cover the remaining distance to Earth’s iciest and least-populated continent.

After Shackleton’s aborted effort on the Nimrod, two men — Norway’s Roald Amundsen (December 1911) and Britain’s Robert Falcon Scott (January 1912) — had reached the South Pole. Shackleton had then thought up this ambitious plan of crossing the 3,200km Antarctic continent on the Endurance in 1914. The dramatically worded advertisement mentioned above — although no records exist of such an insertion — was for applications for crew members for the Endurance, the ship he had chosen for his audacious journey that he called The Imperial Trans Antarctic Expedition.

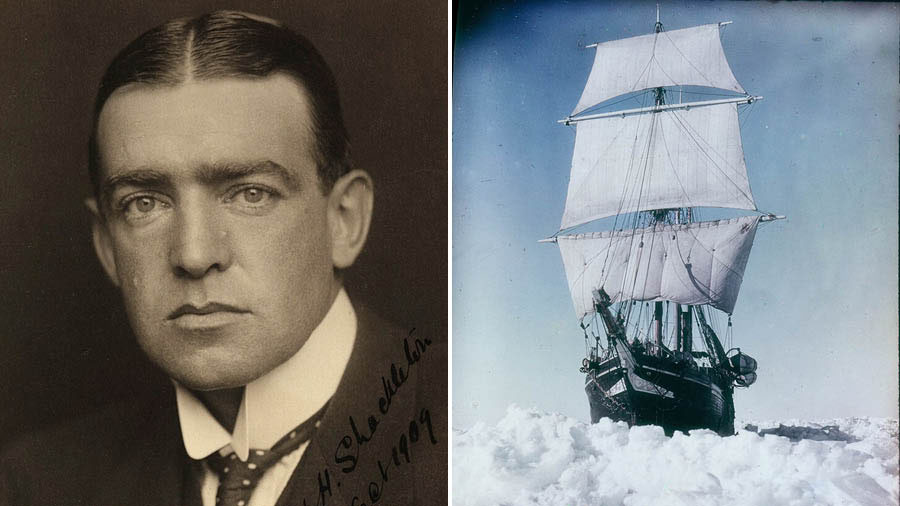

Sir Ernest Shackleton, and (right) the ‘Endurance’ in icy polar waters Wikimedia Commons

That was more than a hundred years ago but Shackleton’s perilous, stamina-sapping adventures, which always fascinated me, seemed to come alive as we sailed from Chile towards this remote continent on board the luxury liner MV Sapphire Princess in January.

Our scheduled first stop after crossing the South American peninsula and the Drake Passage, one of the world’s most treacherous waterways, was Elephant Island — a small island of rock and ice that Shackleton and his crew had reached by three lifeboats in April 1916 after floating for months on an iceberg. However, zero visibility meant we missed the island on the way towards the Antarctic. But more on our expedition later. For now, let’s go back to Shackleton again and the call of the Antarctic that repeatedly drew him to the Pole.

Shackleton was passionate about exploring the icy continent and made three expeditions over a period of 18 years, never afraid to test the limits of his human endurance despite the inhospitable region and the toll it took on the body. His first was as a member of the 1901-04 Discovery Expedition (aboard the ship RRS Discovery) led by Captain Scott as part of efforts to carry out scientific research and explore the largely untouched continent.

Shackleton’s next expedition was on the Nimrod but he had to turn back 98 nautical miles from his destination. His men were exhausted and pressing ahead was no longer an option. “A live donkey is better than a dead lion,” Shackleton is said to have quipped.

A tale of ice and angry seas

Tourists boat past an iceberg on the Weddell Sea Shutterstock

The First World War had started and Britain had already entered into conflict with Germany, which meant the Endurance Expedition had to wait for clearance from the government. It was a turbulent time for England but Winston Churchill, then the First Lord of the Admiralty, sent out a terse, one-word telegraph message — “proceed” — clearing the way for the expedition and what would turn out to be one of the most striking survival stories ever — a stunning tale of icy entrapment, hunger, frigid weather and angry seas.

Shackleton, by then knighted by King Edward VII, and his crew left the English coast in early August as they headed towards the Southern Hemisphere and Antarctica in their ship, a 300-tonne, three-masted wooden barquentine with an auxiliary steam engine. The plan was to walk on the ice shelf and pass through the South Pole to go from the Weddell Sea, part of the Southern Ocean (Antarctic Ocean), to the Ross Sea near Antarctica.

Shackleton had also sent another team aboard the Aurora to carry food for the expedition to the opposite coast of the Ross Sea. The Aurora had to abandon its mission because of devastating storms and had to return to New Zealand. The Endurance was also beset by heavy pack ice. It was a struggle that would last almost a year before the ship had to be deserted and the crew had to manually haul the three lifeboats — James Caird, Dudley Docker and Stancomb Wills — to Elephant Island.

Our scheduled first stop, as mentioned earlier, was this same Elephant Island.

The Santiago skyline Shutterstock

The foot of the Andes to the gateway of Antarctica

Our boarding port was in Santiago, the capital of Chile and one of the wealthiest cities of Latin America. The city, founded in 1541 by Spanish conquistador Pedro de Valdivia, sits in a valley surrounded by the snow-capped Andes and the Chilean Coast Range.

The city, split into two segments by the graceful Mapocho river, offers a mix of old Gothic and new structures. Among the several small hillocks within the city, Saint Lucia Hill is a prominent tourist spot. The 2,000-foot-high hillock accommodates a 65,000sqm park with stairways, fountains and facades.

Ushuaia from the Strait of Magellan along the Chilean coast Indrajit Mookerjee

Another landmark is the San Francisco Church, which has withstood earthquakes of magnitudes of over seven on the Richter scale, tribute to the civil engineering capabilities of the 16th century.

Other landmark sites include the Plaza de Armas, the core of the colonial part of the city, and La Chascona, once owned by Pablo Neruda and is now a museum that houses the works of the poet, diplomat and politician who won the 1971 Nobel Prize in Literature. We ended our drive through the city after dropping in at the Plaza la India or India Park, located in the heart of the city. The park has a fountain with statues of Tagore, Gandhi and Nehru.

Cormorants on land near the Strait of Magellan Indrajit Mookerjee

A befitting prelude to our journey to Antarctica would be our stop in Ushuaia: the gateway to Antarctica. The resort town in the Tierra del Fuego province of Argentina is nicknamed the ‘end of the world’, although another small town — the Chilean settlement of Puerto Williams, the capital of the Chilean Antarctic Province — is a degree further south.

The windswept town of Ushuaia is picture-perfect, bound by the Martial Mountains in the north and the Beagle Channel to the south. A cruise through the channel is a charming ride with abundant views of birds (mostly cormorants) and elephant seals and sea lions basking in the sun.

All the while, Antarctica was waiting for us — beckoning us towards the trail Shackleton had followed in his quest to reach Earth’s last frontier.

Sea Lion sighting from the ship Indrajit Mookerjee

The journey continues in Part II, watch this space.

Indrajit Mookerjee, a distinguished name in corporate corridors, is presently the vice chairman of Texmaco. Travelling and reading are his passions.