Continued from here.

It was now the moment for us to sail through the much talked about Drake Passage. The 800km-wide waterway separates South America’s Cape Horn, the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago, and the South Shetland Islands, a group of Antarctic islands about 120km north of the Antarctic Peninsula. The passage is one of the most treacherous in the world where waves can rise as high as 40 feet. We were apprehensive and most of us had taken anti-vomit pills to survive what is called the Drake shake”. Our captain, Todd McBain, an experienced navigator, later told us we had sailed over ‘child waves’ that rose 20 feet high.

The lighthouse that inspired Jules Verne is built on the easternmost point of Tierra del Fuego Indrajit Mookerjee

The other danger of this voyage is the Antarctic Convergence. As like the Endurance, there was always the risk of our ship hitting the ice and running aground. It is also called the Polar Front and marks the point where the dense, cold Antarctic waters meet and sink below the warmer waters of the temperate and tropical regions. Below the convergence, at 60 degrees south, is the important political boundary of the Antarctic, which does not belong to any nation in the world.

Floating icebergs en route Indrajit Mookerjee

We missed Elephant Island, with zero visibility making it impossible for our ship to approach the island where Shackleton had taken shelter for months after he and his team had abandoned the sinking, ice-crushed Endurance. The lost vessel would be finally found at the bottom of the Weddell Sea in March 2022, nearly 107 years after it went down.

Coming back to our voyage, Captain McBain announced that we were no longer on a cruise and ports of call could change any time depending upon the condition of the sea and the weather.

Of icebergs, whales and penguins

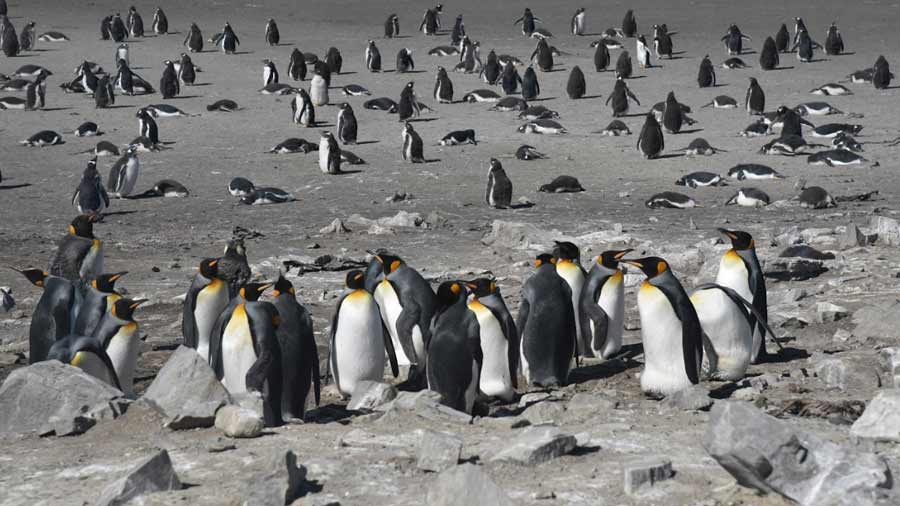

A colony of penguins Indrajit Mookerjee

The next few days, however, offered spectacular views — shelves of ice packs, floating icebergs, and unannounced appearances of whales and penguins at a distance. We navigated our way through the Bransfield Strait and by the King George Island, the largest of the South Shetland Islands. This is the warmer and wetter part of Antarctica. We saw land comparatively free of ice and patches of flowering plants and flightless midge, an insect endemic to the continent. The island is at the northeastern tip of the South Shetland Islands, which act as a barrier from the westerlies blowing from the Southern Ocean. King George Island is the main habitat of Chinstrap and Gentoo penguins.

After a brief stopover at the Admiralty Bay, a protected body of water on the southwestern end of the South Shetland Islands, our ship sailed through the Bransfield Strait. It is a different world here with ice shelves and glaciers silhouetted against a grey sky. The sun does come out sometimes but disappears almost immediately.

A Gentoo penguin on shore Indrajit Mookerjee

As the day drew to a close, we retired to bed, excited about our entry into the Antarctic Peninsula.

The polar chill greeted us the next morning as we watched Captain McBain guide our ship through the Gerlache Strait, against a breathtaking backdrop of mountains even as humpback whales played hide and seek in the water. The Gerlache runs alongside the Antarctic Peninsula and separates the continental land mass from the islands and the archipelagos.

After a brief stop at Charlotte Bay, on the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, we moved to Neumayer Channel, one of the many straits that run parallel to the Gerlache Strait. We were now in the heart of the continent of Antarctica!

The sea around us was bluish, its colour lent by the presence of sea algae that remain submerged under ice most of the year and show up only in summer. A lonely albatross came to greet us, reminding me of Coleridge’s famous poem. Thankfully, all the crossbows of hate and needless cruelty had long dissolved in the spectacular beauty around us.

A humpback whale breaches the polar waters Shutterstock

The winding channel took us to Paradise Island after our ship had manoeuvred an “S”-like curve to come out of the Big Bay. Port Lockroy, a natural harbour, is located here by the lee of Wiencke Island. Port Lockroy houses an old British black timber-frame hut that dates back to the wartime Operation Tabarin, a secret British expedition to the Antarctic during the Second World War. Today it is under the UK Heritage Trust and is home to the world’s southernmost post office. Next to it, stands the US-run Palmer Station research centre. The area is the most populated part of the Antarctic Peninsula.

This region had once been the centre of the whaling industry, with all the signs of indiscriminate hunting — blood stains and bones — scattered around the shore-based processing plant. Fortunately, what visitors experience now is an ice-bound, pristine wilderness, following the signing of the Antarctica Treaty on December 1, 1959. Among other things, the treaty prohibits economic exploitation and territorial claims in Antarctica.

64 degrees, 58 minutes south

Clouds gather over the peninsula Indrajit Mookerjee

A katabatic wind speeded up our ship by about two knots as we exited the Neumayer Channel and into the Bismarck Strait. Captain Todd McBain was happy to present us with a certificate for transiting the Antarctic Peninsula to a southerly latitude of 64 degrees, 58 minutes south.

It was now time to return. We proceeded in a northeasterly direction on the Bransfield Strait to cross the U-shaped Deception Island. It is not exactly an island but the caldera of an active volcano that had damaged local scientific research stations in 1967.

The next day, imposing black clouds suddenly appeared in the sky, partially swaddling us as we sailed on. We finally arrived at Elephant Island, where Shackleton and his men had touched solid ground for the first time in over a year. The island’s unforgiving landscape makes it impossible for human habitation although the Chinstrap penguins seem to live happily here.

Cruising through Bransfield Strait Indrajit Mookerjee

For Shackleton, the call of the Antarctic did not end with his Endurance Expedition. In 1921, after World War I had ended, Shackleton had set sail for another expedition with some members of the Endurance. He had crossed the Polar Front on New Year’s Day, 1922, and reached South Georgia Island. That would be Shackleton’s last port of call. He died of heart failure on January 5 in his cabin on his ship, the Quest, and was buried in a cemetery in Grytviken, a settlement on South Georgia in the South Atlantic Ocean.

The allure of Antarctica is difficult to express in words. Remote, inhospitable, forbidding in its frozen expanse, the icy continent has a beauty that is mind-blowing and a pull impossible to ignore for those willing to test their limits of physical and emotional endurance. It is precisely this attraction that prompted the adventurer in Shackleton to make not one but three expeditions to the world’s last frontier. For people like us, inveterate travellers but for whom the whole world beckons, one expedition to the Antarctic is probably enough.

Enough to sustain a lifetime of memory.

Indrajit Mookerjee, a distinguished name in corporate corridors, is presently the Vice Chairman of Texmaco. Travelling and reading are his passions.