Georgi Gospodinov feels at home wherever people believe in books and stories. And the Front Lawn shamiyana at Hotel Clarks Amer during the recently held Samsung Galaxy Tab S9 Series Jaipur Literature Festival packed to its capacity, despite a cold and rainy start, with a new and eager audience ready to listen to his stories and learn about his books, certainly made him comfortable and elated as well. The winner of the International Booker Prize 2023 was on his first India trip and he brought a copious amount of sunshine as he discussed his award-winning novel Time Shelter on Day 4 of the prestigious literary festival in the Pink City.

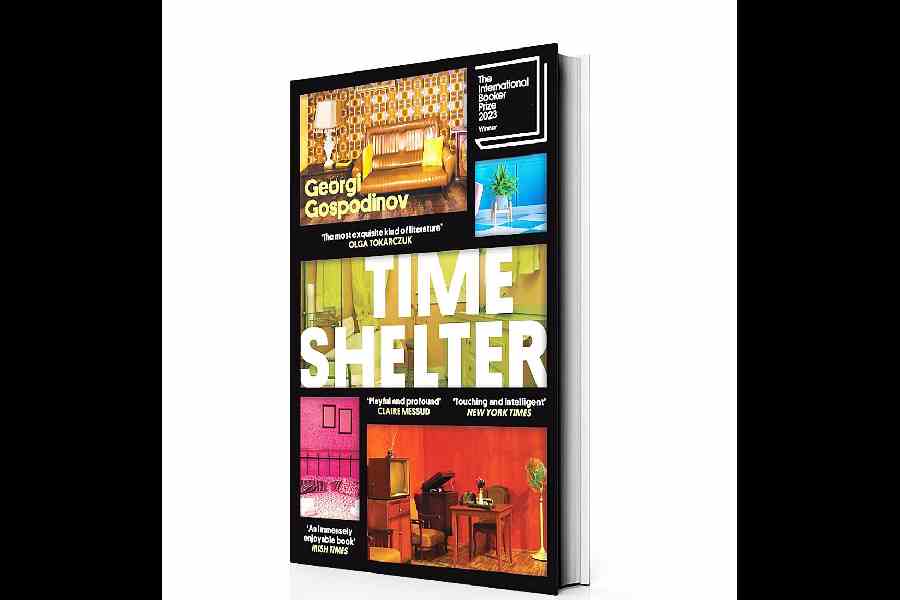

Published in 2020, Time Shelter, Gospodinov’s third novel, translated into English by Angela Rodel, brings in the thought-provoking concept of the ‘clinic of the past’ for patients of Alzheimer’s disease. It topped the bestselling books charts in Bulgaria and also won Strega European Prize before bagging the Booker. His other two noteworthy novels include The Physics of Sorrow and Natural Novel. The Bulgarian writer who is also a playwright and a poet, has written many short stories and his novels have been translated into over 20 languages, reaching a large audience of readers globally. In his late 50s, Gospodinov talks about having many fears, why novels should be like a laboratory, and why he likes mixing poetry with prose.

Welcome to India, Gospodinov. This is your first trip to India and you are at one of the biggest literary festivals of the country. How are you feeling now that you will be connecting to a new set of audience?

Yes, this is my first trip to India. I’ve heard great things about this legendary festival in Jaipur and I’m really glad to be invited. I know it’s one of the places with a large and curious audience of reading people. And where there are reading people, people who believe in books and stories, that’s where I feel at home. I have always approached these events very emotionally and openly. In the end, I would like everyone to walk away richer with a few stories. The exchange of stories came before the exchange of money.

You have achieved a milestone by winning the International Booker Prize. If you were to look back at your journey and evaluate, how do you think you and your craft have evolved as you approach your 60s?

I started writing very early, as soon as I learned the letters. In the beginning, I wrote down a scary dream that was repeating very often. And when I wrote it down, the nightmare didn’t occur again. (But I didn’t forget it either.) That’s how I knew there was some kind of miracle here. I had many fears, and I still have them, but when I write, I have the feeling that they subside, at least for a short time. I still keep my notebooks with the first poems; some of them were published in local newspapers (I come from a small town in southeast Bulgaria.) I like to experiment, I’ve written in almost every genre — poetry, essays, short stories, novels. I’ve also written an opera libretto and a graphic novel. Looking back, I see that literature has always saved me and it is one of the few things that has never betrayed me. I wrote, as I said, to save myself from my fears. I also write to preserve for a little longer things that are precious but perishable. I have written in days of despair and in days of quiet joy.

You are not new to awards and have earned many at national and international levels. What does the recent award, the International Booker Prize, mean to you and to writers of your country, given that you are the first Bulgarian national to win this award?

For someone full of hesitations like me, awards are a sign that what you are doing is not completely meaningless. The International Booker is a big and remarkable award. It draws attention to writers from around the world, to literature in translation. Even a nomination for this award is something that marks the nominated book forever. Yes, it was the first time a book by a Bulgarian writer made it to the nominations. I was delighted because I have always dreamed of books being judged not for where they come from, whether from a ‘small’ or ‘big’ language, but for their qualities, their ideas and their ability to move the reader. I’m sure small languages can and should talk about big things, too. In their motivation for the prize, the judges noted that this novel is surprisingly bold and brave, and that made me very happy, I admit. I’ve always thought that a novel should dare to talk about all kinds of things, to expand the field of literature, to be not just entertainment but a challenge, a laboratory, an invitation to conversation.

Have things changed in any way after the global recognition? Does it make you conscious in any manner?

Yes, my books are reaching more people and that’s wonderful. But it also makes it harder to find a shelter in time for writing, which is a problem.

Your last novel, Physics of Sorrow, centred on human emotion. Time Shelter too is about holding on to or revisiting memories or emotions of the past. Do you like exploring the human psyche and emotions?

Physics of Sorrow starts from several injustices. The first is that we have an exact science for all sorts of things, even for the smallest particles, but we don’t have an exact science for sadness. We don’t know its weight, nor its aggregate state, nothing. The other injustice had to do with those whom we have turned into monsters because of our own sins. Such is the case with the myth of the Minotaur. If we read this story carefully and with empathy, we will see that the Minotaur is not the beast we know, but a child abandoned and locked in a labyrinth by his father. For his mother, Pasiphaë, had sinned with a bull. So there’s a different take on this myth in The Physics of Sorrow, and it seems plausible to me. But at the heart of it all is my interest in the human being and beyond that in every living being with all their sorrows, doubts, impermanence and hesitations.

The word ‘Shelter’ in the title is positive and also the concept of revisiting or nostalgia is considered positive. When did you realise that it’s much more than that and dangerous too?

Yes, the idea for this novel and Gaustin’s idea for the ‘Clinics of the Past’ was quite positive at first. And I still think that these clinics and places to revisit the past help dementia and Alzheimer’s sufferers. But at some point in 2016, two things happened that made me realise that in fact the past can be used as a weapon. It had to do with the election of (Donald) Trump and with Brexit. In the novel, each European country makes its own referendum for the past to choose its happiest decade in which to live. But is this harmless?

Angela Rodel has been a regular translator of your works. What is it about her craft that you like? Also, you said in one of your interviews that your book is a tough one to translate. What convinced you about Angela to trust her with the English translation?

Angela Rodel came to Bulgaria 20 years ago because she was captivated by the Bulgarian voices, by performers of authentic folklore. She sings beautifully herself. I trust her as an interpreter because she has an ear and a heart for the sentences, for the narrative voice. And that’s very important for me.

Are you a poet first and a novelist later? How do you keep the two separate or do you keep them separate at all?

I joke that I like to smuggle poetry into my novels. I consider poetry one of the most important arts. Poetry teaches brevity, modesty, intensity of meaning, and its ability to make unexpected associations, to bring disparate things together is part of its superpower. Poetry is at its best when it has to describe the ineffable, that for which we have no words. All of which I think helps when you sit down to write a novel. I don’t separate the two genres, I like to mix them.

Any Indian writer who is in your list that you want to read/explore?

One of the best books I’ve read in recent years was Aravind Adiga’s White Tiger. I also like Rana Dasgupta’s writing. I would like to read Geetanjali Shree soon, who was an International Booker (2022) winner.