Surely, football’s coalition of immortals is now invincible?

Edson Arantes do Nascimento has just crossed over. Gone, in every earthly sense. Like all things that breathe must go. Taken by age and, in this case, weakened too, by the lethal touch of disease.

Right then, Edson is dead. The Brazilian king of the beautiful game is dead. No dispute about that.

Remember the date: December 29, 2022.

Was it an untimely death?

Not really. He was 82.

Even the greatest have to leave when their time’s up. And Edson’s time was up.

But wait. A minor clarification: it was Edson the mortal whose time was up. Pelé the immortal lives.

Pelé of the illusory feet; Pelé of the immaculate header; Pelé of the intrinsic pace; Pelé of the thousand goals; 1,200, in fact, and some more. But that’s for the necessary statistics of temporality. What goes beyond statistics are those moments that offer glimpses of eternity. The moments when play becomes an idea, an instant of exuberance that offers a thousand redemptions. Vicarious redemption from the tedium of familiarity, of conflict and of struggle, in the sudden, exquisite knowledge that beauty is possible where it seemed improbable.

Like the one in the final at Mexico City, 1970, when he leapt high, hung in the air’s buoyancy before heading into the Italian goal for Brazil’s first — and his last in a World Cup — in a 4-1 romp. Even gravity, bullheaded otherwise when it comes to the laws of physics, seemed to have acquiesced in that moment of sublimity.

There’s a question that springs up off and on, now more than ever after Lionel Messi recently added the one trophy so long missing from his cabinet of glory: who is the greatest footballer ever? Pelé? Diego Maradona? Johan Cruyff? Or is it Messi or Cristiano Ronaldo? That’s a pointless debate, as futile as all-purpose certainty.

Going back to Pelé’s World Cup days, the first hint of his brilliance had come in 1958 against Wales, at Gothenburg, Sweden, when the 17-year-old, whose name few had heard before, balanced the ball on his chest, back to the goal, turned past a bewildered defender and then slotted home a low finish.

Pelé as an idea

Somewhere along the way, between Sweden and Mexico, between his first World Cup goal and his last, Pelé the footballer had transformed into Pelé the idea. A transcendental idea that worked at multiple levels: social and economic; an idea that promised a sort of equity, inspirational in his ascent from barefoot, rags-rolled-up-into-ball poverty and, ultimately, in the unifying appeal of genius.

Only a few things on earth offer that scope. Sport is one, in its race-less, terrain-less ability to command allegiance. Precisely why thousands in this part of the world, far away from Brazil and the fabled charm of Latin American soccer, would turn out on a day late in the 1970s to watch an aging wizard, hoping he would conjure up for the football-mad city one last act of sorcery. It didn’t happen, but that’s another story. But the idea remained, as indelible as memory.

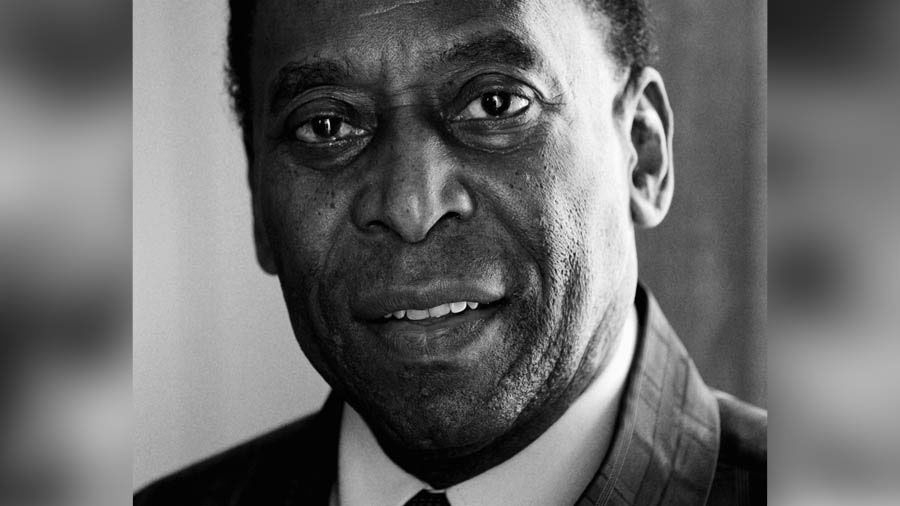

What does Pelé’s passing mean? At the simplest level it means the end of an era. An era of beautiful football and glorious triumph Christopher Furlong/Getty Images

So, what does Pelé’s passing mean?

At the simplest level it means the end of an era. An era of beautiful football and glorious triumph, the uninhibited romance of a band of men who played the game as if they were poets from a pagan age, whisked magically into the present, their play comparable to a symphony where movements melt from one to another and back again.

Even the names they were known by were exotic — Tostao, Vavá Garrincha, Rivellino, Jairzinho, Carlos Alberto. Pelé, in his transmutation from Edson, embodied the spirit of that era, in the pacy, athletic suppleness of his swerves and thunderclap volleys, the perfect coda to the beautiful game. As if a letter less had lent an added verve to his play, although Pelé, named after Thomas Edison, the American inventor, apparently never liked his nickname that would become synonymous with the game.

Pele, surrounded by young autograph hunters, in the UK in the 1960s Central Press/Getty Images

But there’s something intrinsically temporal about an era, defined as it is by time. By mathematical time; time as a series of linear, countable moments.

What happened on December 29 was that time, the inexorable reaper, deferred to Pelé the idea, freeing it from the inevitable human fact of cessation. In other words, from the time-bound constraints of an era to an idea free of any timeline.

Only those truly immortal have that ability — to bend time to their genius.