The word ‘booster’ might have entered the global lexicon courtesy the Covid pandemic, but four decades ago, it used to be bandied about with abandon in the streets and schools of Kolkata. Thanks to a pandemic of a different kind — less fatal, but no less emotionally traumatic — that had afflicted the youth of the city. The year was 1982 and Spain was hosting the football World Cup and we needed a booster to save our souls and evenings.

I was about to turn 15 and while I had fragmented memories of the 1978 tournament, Spain’s was the first vivid, technicolour World Cup to be etched into my consciousness. For a sports-obsessed teenager and his similar-minded cohorts, largely fed on cricket, there could not have been a better initiation into international football than the 1982, and then the subsequent 1986, World Cups — without doubt the two outstanding tournaments of the modern era.

(L-R) Johan Cruyff, Mario Kempes and Zico Wikimedia Commons

International sporting coverage barely existed in India then. There would be odd snippets and highlights of cricket and Wimbledon, but anything else was non-existent. We relied largely on BBC radio and let our imaginations run wild thinking of Cruyff, Zico and Kempes and took out our collective frustrations on our very entertaining but less talented local heroes of East Bengal and Mohun Bagan. A poor pass would warrant a stream of Bengali invective with a sarcastic “nijeke Zico bhabis” (do you think you are Zico) added for good measure. The poor sod had no such pretension, but what is logic in the face of youthful angst!

First taste of international football

The year 1982 changed all this somewhat. India acquired the right to host the Asian Games. The country was then led by Indira Gandhi, who wanted to make this sporting event a springboard to modernise infrastructure in Delhi and also, public broadcasting. India was a socialist country with one channel of free public TV. Entertainment was sparse barring odd movies and very rare live cricket. With the Asian Games on the anvil, with the help of the USSR (those were the days my friend!), India sent up a couple of satellites, thus ensuring the ability to beam events live if the media ministry could afford it. The purpose was to ensure the Asian Games reached urban households at least but it opened up wider possibilities of international events being beamed into our homes. Along with that came colour TV and a plethora of local manufacturers.

The Asian Games also meant allocation of funds to various sports to prepare for the contests. For the first time in living memory I remember the national football team being given due importance. A legendary manager, much beloved of Indian football aficionados of a certain age, PK Banerjee was appointed the head of the national team and he sought to build a competitive side largely around players from the big Kolkata clubs with a sprinkling of talent from Punjab, Kerala and Goa. PK, as he was called, pushed and prodded the powers that be for an international tournament. And that resulted in the inaugural Nehru Cup in Kolkata in 1982.

This was our first taste of good football. There was no Salt Lake stadium, so the venue was the Eden Gardens, the world’s largest cricket ground, with the football field marked from the high court and Maidan ends. The location was excellent, easily accessible from schools and offices, and each game attracted upwards of 80,000 spectators.

China, South Korea and Yugoslavia sent formidable sides. In fact, the bulk of the Korean side would go on to play in the 1986 World Cup and included the likes of Choi Soon Ho, the first Asian import to an European league. Italy sent a scratch Olympic side. But the showpiece of the tournament was Uruguay. Having failed to qualify for the 1982 World Cup, their first team arrived for the Nehru Cup. Even the memory of watching them live gives me goosebumps! They had flying wingers like Vanencio Ramos and Nestor Montelongo and great strikers like Jorge Da Silva — all big names in Latin America. The icing on the talent cake was the elegant Enzo Francescoli, who, of course, would find global fame shortly and remains one of the greatest Uruguayan players ever. Elegant and tactically masterful, the team mesmerised us with their without ball runs, precision passing, exquisite overlaps by wing backs — things we did not know existed in football.

That tournament truly whetted our appetite for international football and by the summer, the excitement around the World Cup had reached fever pitch. The local sports media provided extensive build-up coverage as did the two wonderful English sports magazines that we remember with great nostalgia, Sportsworld and Sportstar.

A Belgian journeyman starts a revolution

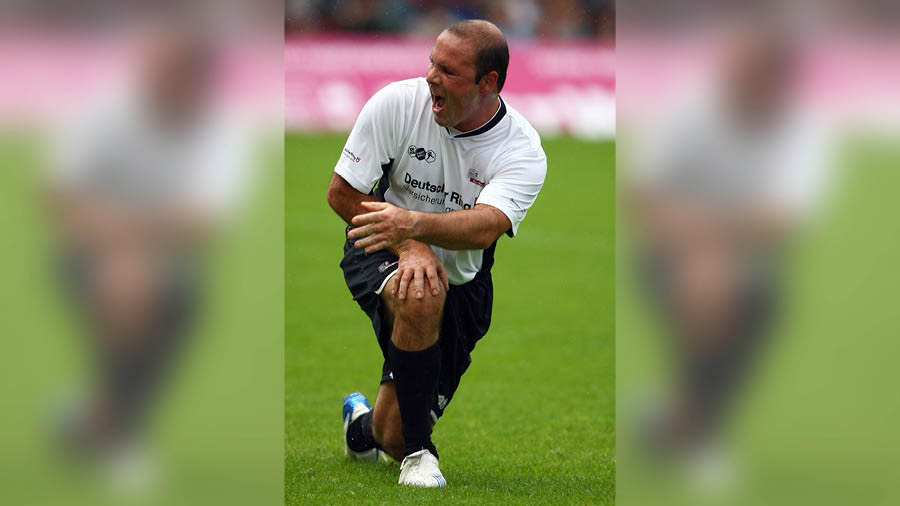

As history teaches us, relatively obscure incidents and individuals often trigger a revolution. Cue Kerry Packer in cricket or Nic Pilic in tennis. For football, it was Jean Marc Bosman, a journeyman Belgian footballer Christof Koepsel/Bongarts/Getty Images

A pause here to explain why the World Cup itself was such a different animal then in footballing terms. As history teaches us, relatively obscure incidents and individuals often trigger a revolution. Cue Kerry Packer in cricket or Nic Pilic in tennis. For football, it was Jean Marc Bosman, a journeyman Belgian footballer. In the 1980s, football, while a popular global sport, remained a domestic game from a media coverage perspective. Even in England there were odd local games on BBC, but largely limited to “match-of-the-day” type highlights shows. In Asia, coverage of European football was non-existent.

The World Cup was the great showpiece event once in four years for a global audience to follow and watch superstars about whom they only read odd snippets about in the media. Club loyalty outside of national boundaries was a very niche thing — I supported Manchester United in the 1980s (when they won nothing, should I be accused of “glory hunting” — I just wanted to be George Best!), but I would have been a part of a motley group of only around 100 across India. In contrast, Man U cafes and fan clubs of thousands dot all urban cities now.

This began to change across sports in the 1990s with the arrival of satellite TV and corporations like Sky making lucrative bids for TV rights and beginning to beam European leagues and cups across the world. The tipping point was in 1995. Bosman at that time was an out-of-contract footballer with a Belgian club and dropped from the first team. There was a possibility of a move to a lower-division French club but this was refused on account of the latter failing to meet the transfer fee. Meanwhile, Bosman found himself out of the side and on reduced wages. He proceeded to go to the European Court of Justice seeking redress on grounds of being denied employment.

In 1995, the court passed a landmark judgment that established sportspersons as self-employed professionals, who when out of contract had the right to work across EU borders on the basis of the “free movement of labour principle”. Bosman spent an odd year in France but the impact on football was revolutionary. The floodgates were opened for talent to flow freely, first across European borders, and then, globally. Sky made its second and significantly enhanced bid for TV rights across Europe and Asia. Football was now big business and the Champions League and major European domestic leagues became lucrative platforms for global talent to showcase their skills.

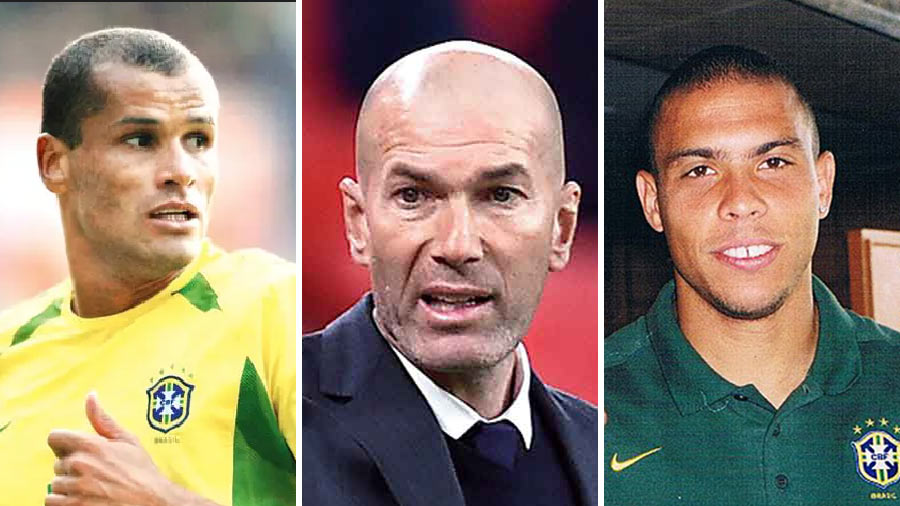

(L-R) Rivaldo, Zinedine Zidane and Ronaldo Wikimedia Commons

Suddenly Zidane, Ronaldo (the original Brazilian one), Rivaldo and the likes were being seen day in and day out, and were no longer the exotic mythical superstars of the 1980s. This has changed the World Cup, which is now nearly an aberration, a break from the regular football season and at best, a nice exhibition tournament. Less tribal and tense, so a pleasant distraction to follow some national football before you get back to the war zones of Man United vs Liverpool.

Dhaka to the rescue

Back then to 1982. The excitement was all good but how to watch? Indian TV did not have a plan for live coverage. Between bouts of mulling and sulking, we got wind of Bangladesh TV beaming matches live and that we could catch these if we turned our rooftop TV antennas towards Dhaka. Suddenly unfit and unadventurous Bengalis like myself were dangling precariously from rooftops trying to turn the antennae towards Dhaka to catch a glimpse of Zico and Rossi.

Then came this amazing invention called the booster. A couple of local electronic stores announced that this small aluminium device fitted to the antennae would result in clear, static-free coverage from Dhaka. Bangladesh then was a beneficiary of US largesse, so not just live football, this opened Kolkata’s access to Bionic Woman, Six Million Dollar Man and Magnum PI, a world away from the agricultural and religious lectures and mundane variety entertainment shows being dished out by the local TV.

The ‘booster’ inevitably resulted in class wars, the haves and have nots. Those with the booster boasted of having not just first seen Spain against Northern Ireland but then followed that up with Magnum PI, while others like myself had been left to do maths homework, or even worse, watch half an hour of Bengali and English news on TV.

A scene from 'Bionic Woman'

Sometimes one got lucky on a clear day, when some odd orientation of the antenna resulted in clear signals to Brazil vs Argentina live, and then that game to beat all games — Brazil vs Italy, the day the music died, when the most eye-pleasing attacking side in the history of football was undone by magnificent tactical defending and counterattack. Brazil’s loss to Italy brought heartache and sorrow to many Kolkatans, but with the embellishment of time, remains the best game of football at least I have ever watched (thanks to YouTube, the game is still available to watch in full).

(L-R) Gaetano Scirea, Socrates and Paolo Rossi Wikimedia Commons; Duncan Raban/Allsport/Getty Images; Wikimedia Commons

The classical defending of the Italians, who had among their ranks, Scirea — along with Aari Haan and Beckenbauer perhaps the greatest libero in football history — Cabrini, Bergomi and Graziani. And the ability to counter with Tardelli and Conti, topped off by a classic finisher in Paolo Rossi. Brazil, of course, was imperious in attack, often playing with nine names in the opposition half. Up front, Zico and Socrates produced genius passes and goals and full backs like Junior, Oscar Leandro and Luisinho produced mesmeric runs. Oscar and Junior were central defenders and scored incredible field goals, often playing in striker position on overlap. It left them exposed and eventually, Rossi punished them, but football was the winner that day — a celebration of Joga Bonito.

In 1986, Diego Maradona’s individual genius would split loyalties in Kolkata between Argentina and Brazil TT archives

In four years, Diego Maradona’s individual genius would mesmerise us all and split loyalties in Kolkata between Argentina and Brazil. But 1982 was the greatest for team football — France, Germany, Poland, Brazil and Italy had such great sides and left us with beautiful memories of a long forgotten idyllic childhood in Kolkata.

(Basab Majumdar is a London-based finance and strategy consultant and enthusiastic tennis player. He passionately follows and writes about sports)