Kolkata, or Calcutta, as it was known for majority of its existence to the western world, has a rather unique history. Despite being a rather younger metropolis as compared to say a Delhi or Lucknow or even a Patna, history played out in such a way that Calcutta became a melting pot of cultures from across the world. All through the years of English rule and especially during the 18th and 19th centuries, adventurers and prospectors streamed into the city. Many passed away into the anonymous pages of history but some, left an indelible mark on the city’s history.

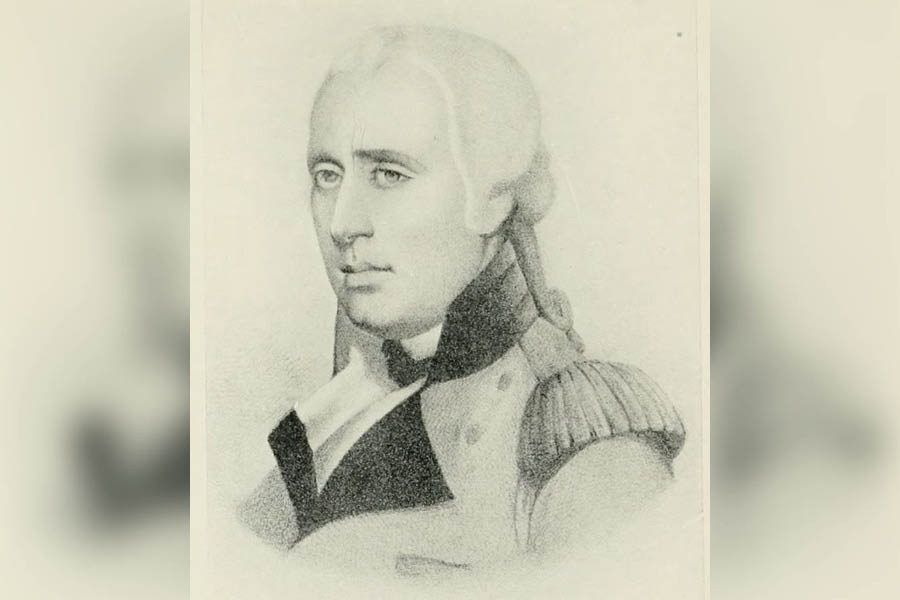

Born in distant Forfarshire of Scotland in 1746, Robert Kyd was one of the many young men who arrived in Bengal from the Isles with dreams in his eyes. In 1764, he joined the Bengal Army as a cadet and soon, received his full commission as an ensign. He had a respectable career in the army, rising to the rank of a lieutenant colonel in 1782. He eventually was appointed a secretary to the military department of inspection in Bengal – a position he held up till his death in 1793 in Calcutta. But his military career is not Robert Kyd’s legacy to the city. As a matter of fact, his real legacy exists today in all regality on the other side of the Hooghly.

Indian Botanic Garden

In an agrarian country like India with vagaries of weather, a devastating famine was never far off. The Great Bengal Famine of 1770 is believed to have killed between 7 and 10 million people. Robert Kyd, aside of his military career, had a passion in life: it was horticulture. He had acquired a country house in Shalimar in Howrah, where he had patiently and lovingly built an extensive garden. Kyd, observing the extreme famines of India, had been working on a plan to identify and import plant species that could be grown in controlled environments and can solve food scarcity in times of famine. But to make this commercially viable was beyond Kyd’s private means.

In the mid-1780s, Kyd placed the idea of a botanical garden to Sir John Macpherson, the acting governor-general of Bengal. In a written proposal to Governor-General John Macpherson to establish the garden, Kyd stated it was “not for the purpose of collecting rare plants as things of mere curiosity, but for establishing a stock for disseminating such articles as may prove beneficial to the inhabitants as well to the natives of Great Britain, and which ultimately may tend to the extension of the national commerce and riches”. The plants Kyd mentioned included the sago palm from Malaya and the Persian date.

Macpherson, in turn, referred Kyd’s proposal to the company board of directors. The plan was approved on July 31, 1787, and Kyd was made an honorary superintendent of the Indian Botanic Garden. By 1790, Kyd had 4,000 plants in the garden, mainly obtained from East India Company’s voyages. The company’s court of directors supported Kyd’s ambitions to establish cinnamon, tobacco, dates, Chinese tea, and coffee in the garden due to its economic benefits.

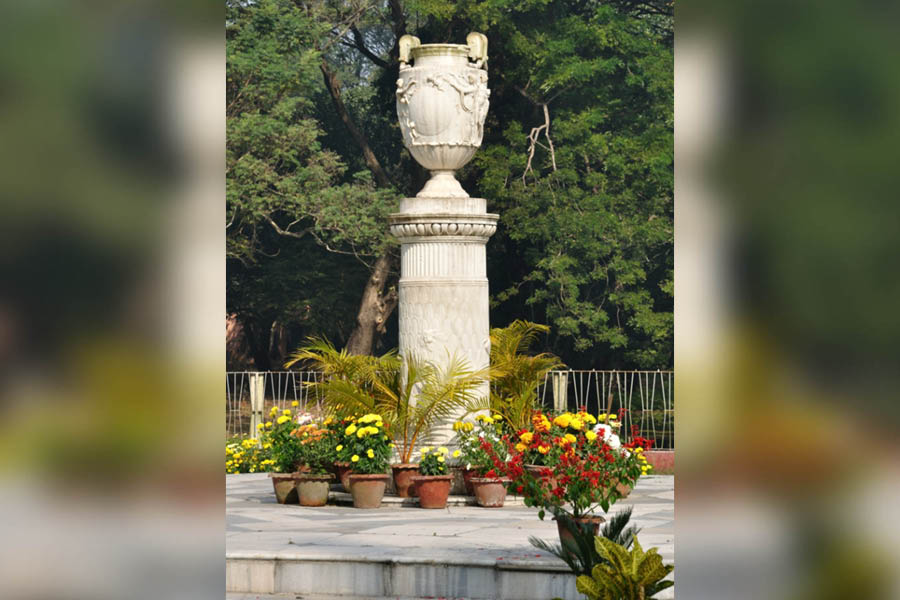

Memorial to Robert Kyd at Indian Botanic Garden

When the botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker visited in 1848, he noted that it (Calcutta Botanical Garden) had “contributed more useful and ornamental tropical plants to the public and private gardens of the world than any other establishment before or since”. Dalton further noted: “Amongst its greatest triumphs may be considered the introduction of the tea-plant from China ... the establishment of the tea-trade in the Himalaya and Assam is almost entirely the work of the superintendents of the gardens of Calcutta and Seharunpore (Saharanpur).”

Kyd was so in love with the labours of his love that he made a request in his will to be buried on the grounds of his beloved Botanic Garden without any religious ceremony. This, however, could not be complied with and after his death in 1793, Kyd was buried at the South Park Street Cemetery. Kyd’s successor as superintendent, William Roxburgh named a genus in the family Malvaceae as Kydia – in honour of Robert Kyd, A beautiful urn of Kyd was also placed as a memorial in the Indian Botanic Garden that he founded.

But Robert Kyd wasn’t the only member of his clan who enriched Calcutta and Bengal with their works. His first cousin, one removed was Lieutenant-General Alexander Kyd, who had a stellar career in the East India Company army and later in his life, held the vital post of surveyor-general of Bengal Presidency. Alexander Kyd had a keen interest in music and had managed to collect five precious stringed instruments – three Stradavarius, one Guarneri and an Amati. The last one will certainly interest fans of Satyajit Ray’s sleuth, Feluda, since an Amati instrument played an important role in one the detective novels. Alexander Kyd passed away in 1826. He had two sons, James and Robert. While the latter followed his father into the army, the former had a different interest.

The Hon’ble East India Company’s ship ‘Castle Huntley’

James Kyd was born in 1786 in India and later travelled back home to learn the art of shipbuilding. In 1800, James Kyd returned to Calcutta and started work as apprentice to famous shipbuilder A. Wadell. Kyd eventually succeeded Wadell as master shipbuilder of East India Company in Calcutta. Over a career spanning more than three decades, James Kyd built a large number of ships, steamers and yachts for the East India Company as well as other buyers. Among his most impressive creations were the 1,276-tonne East Indiaman Castle Huntly and the 1279-tonne General Kyd – christened after his father. It is believed that the neighbourhood of Kidderpore may have got its name from James Kyd – in honour of Kyd building the lock gates that connected the port to the Hooghly river.

That is the not the only touch of Kyd left in the city. A road off Jawaharlal Nehru Road just before the Indian Museum is named Kyd Street – after one of the Kyd family members. And above all, there is sprawling botanical garden that continues to be an oasis of green and carry the legacy of the Kyds of Kolkata.