Even as India celebrates the 75th year of its Independence, does the deep-running scar inflicted by barbed wire still hurt the people on both sides of it? The answer cannot be found in political endgames or pedantic speculations but in memories, memorabilia and stories locked inside the heart.

My Kolkata recently caught up with Aanchal Malhotra, an oral historian and author, during her latest visit to Kolkata for a book-signing event at Starmark, South City Mall, to discuss the impact of the Partition which is still evident today in the subcontinent.

Aanchal Malhotra at a book signing event in South City Mall. HarperCollins Publishers India

My Kolkata: As an oral historian, you hear intensely personal stories from people. How do these tales — often very contrasting — form the basis of oral history?

Aanchal Malhotra: Over the years I have learnt not to homogenise any experience of the Partition even when it comes to stories from within a single community. For instance, Bengal and Punjab are two provinces that felt some of the most violent consequences of the Partition, yet not all Bengalis nor all Punjabis had the same experience. Sometimes even a single testimony can be full of contradictions, for the Partition gave rise to a spectrum of emotions — while recalling the past, one can feel fear, pain, longing and loss simultaneously.

It has also to be considered that the survivor’s memory is not vague. I was often surprised by the specificity of what they recall — sometimes what they were wearing when they left their home, or the name of a friend left behind or something they wished they’d carried. This is all while recalling the past over six decades later, and some of these stories or details have found their way to the next generations as a kind of inheritance.

Oral history allows us to consider far more detailed and subtler testimonies from the past than the media has propagated the Partition to look like. Innumerable religious, ethnic, linguistic, cultural nuances have either gotten lost or been built because of migration. I think one of the privileges of recording oral testimonies is to bear witness to the many lived experiences of the Partition.

Bengal felt the tremors of a geographical divide quite a few times. Have you ever come across a memory from Bengal which left a profound impact on you?

Aanchal Malhotra: An interview with a young man from Kolkata comes to mind; it can be found in the chapter on Belonging in my new book, In the Language of Remembering (Harper Collins, 2022), he spoke to me about the multiple migrations undertook by his family back and forth across the eastern border; how both sides of his family tried to save the land they left behind in what would become East Pakistan and later Bangladesh. In that story one could feel the calling of homeland beyond borders.

In another story found in the chapter called Borderlands, a woman tells the story of her ancestral home in Karimganj, Assam, barely 365 metres from the border. What intrigued me the most was when she said that the Kushiyara river was the current border between India and Bangladesh. She could stand on the banks and watch the daily life of people across the border, even hear the celebrations during a festival. “If someone didn’t have prior knowledge of the river being a border,” she said, “they would assume It was part of the same land.’ I found that fascinating.”

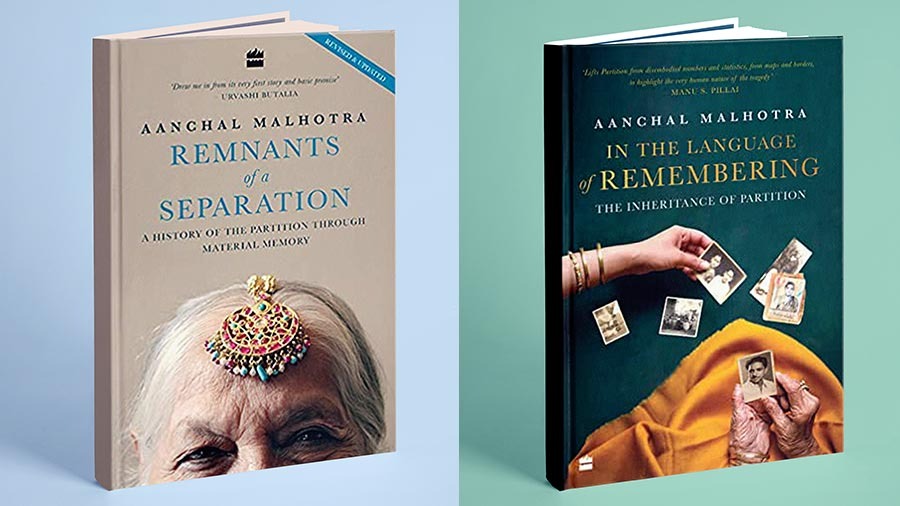

The two books contain interviews of Partition survivors and their descendants HarperCollins Publishers India

The stories of the Partition are often quite traumatic and emotionally draining. What are the most common problems that oral historians face during interviews?

Aanchal Malhotra: Through the course of my research, I’ve often thought that we still don’t have a vocabulary of trauma to discuss the Partition. There is not only the difficulty on the part of the survivor in uttering what had happened and gradually has been rendered unspeakable, but also the incapability of the descendant to demand the immense emotional sedimentation of the Partition. In many of the interviews conducted with survivors and descendants, I found that we were building a new language to speak about a historical loss. This language is not only verbal, but also gestural, often built with silences and the things that remain unsaid but inferred.

Seven decades on, it remains hard to speak about the Partition — whether it is an experience lived or inherited — and I have enormous respect for my interviewees who answered questions with sincerity that maybe I wouldn’t have been able to, had someone asked me.

How do you reconcile the contrasting versions narrated by people who have experienced the consequences of the Partition?

Aanchal Malhotra: Well, the Partition has different meanings for the three countries of the erstwhile empire — for Pakistan, it meant the gaining of a nation; for India, it was a loss of land; and in Bangladesh, the year of independence, 1971, holds prominence over 1947 in collective memory. Perhaps when there is no shared understanding of a historical event, it’s even harder to work towards reconciliation, but we can always acknowledge and respect each other’s versions of the truth.

As I was putting the interviews together for my new book, they seemed to loosely hold together the shape of an undivided subcontinent. These tales describe how the burden of the Partition is being carried forward in multiple and often complex contradictory ways.

Aanchal Malhotra is also a co-founder of the Museum of Material Memory. Aanchal Malhotra/Instagram

Your new book In the Language of Remembering deals with the descendants of those who had suffered the Partition. What do you think is the relevance of these interviews?

Aanchal Malhotra: The interviews in this book had been recorded for a period of over nine years since 2013. I never thought anyone would be interested in reading second-hand memory. But over the years, the Partition has resounded privately within families through habits, secrets, memories, silences and evoked publicly in the geopolitics of the subcontinent, and more recently, during the anti-CAA/ NRC protests. It became clear that the Partition as a memory, as a wound, as a legacy has persisted from the past into the present and may continue to be carried into the future. Which is why this archive is important — it helps us to see how memories get disseminated, how memory patterns emerge and how trauma can be passed down through generations.

How different is your new book from your previous one, Remnants of a Separation (Harper Collins, 2017)? Will the readers be able to pick up the pieces from where they had left them?

Aanchal Malhotra: I would say In the Language of Remembering is broader in scope. It covers an area from Afghanistan to Burma, from Kashmir to Karnataka. My first book was about the material artefacts and heirlooms that families chose to carry when they migrated due to the Partition. But this book focuses on the passage of memory from one generation to the next.

But there are some stories that overlap. For instance, my previous book mentioned a house called Shams Manzil in Jalandhar that a Muslim family had fled from as they migrated to Pakistan. After several years, the gentleman who once resided there came back to India to visit the house and found a Sikh gentleman and his family living there. They welcomed him in as the original owner of the house. Then a few years ago, the descendants of the Sikh gentleman got in touch with me after they’d read the story of Shams Manzil as they wanted to narrate their side of how they came to live in that home. My second book records this story, bringing it full circle.

You are the co-founder of the Museum of Material Memory. How did that come about?

Aanchal Malhotra: I co-founded the museum with my friend Navdha Malhotra in 2017. It is a crowdsourced archive that invites South Asians from around the world to write about the heirlooms and through them the stories of their family. The idea was inspired by Remnants of a Separation, but it branched out from the original theme of the Partition to include general objects of age so that people may become proud bearers of their family histories through the process of writing and conversations around the objects.

Since your work deals with material memory, what is the one memory that you will be taking back with you from Kolkata?

Aanchal Malhotra: Every time I come to Kolkata, I return laden with stories. On this trip alone, every reader has told me a story or two during my book-signing events. It’s a privilege to be on the receiving end of these snippets of the past, and I’m in awe of the care and respect people give to history and memory in this city. I love coming back to Kolkata.