A young Narayan Debnath used to sit on the steps of his family’s jewellery shop in Shibpur, Howrah and watch the antics of boys his age, who would gather at Bidhu moyra’s shop across the road and play pranks on the cranky confectioner.

Those memories gave him the confidence to take up the challenge to produce the comic strip Handa Bhonda as a regular feature for the children’s magazine Suktara from June 1962, taking over the mantle permanently from illustrator Pratulchandra Bandyopadhyay, in whose hands the bumbling boys had made sporadic appearances, alone or together, since October 1951.

By way of inspiration, there were the talkies of Laurel and Hardy and the animation reels of Tom and Jerry shown in cinema halls before Hollywood films. Comic strips with local characters were unheard of, save for Pratul Chandra Lahiri’s cartoons in Jugantar (Kaafi Khan’s Sheyal Pandit) and Amrita Bazar Patrika (Khuro).

So it is Debnath who can be said to have pioneered the tradition in Bengali literature, singlehandedly manning the supply line for Handa Bhonda and Bantul the Great in Suktara and Nonte Fonte in Kishore Bharati for the next five decades. His last instalments of Bantul and Handa Bhonda were sketched in 2017 and published in the 2018 Puja edition of Suktara, barely three-and-half years before he bid adieu to his legions of fans, young and young at heart, at the age of 96 on January 18.

Star illustrator

Handa Bhonda, Bantul the Great and Nonte Fonte may have attained cult status and made him a legend late in his lifetime but there is more to Debnath’s legacy than these three comic strips.

He was an illustrator par excellence and his covers made the fortunes of several local publishers in the ’70s. Santanu Ghosh, who has done Debnath’s fans yeoman service by collating his works across genres and publications over 15 years, had heard the artist’s sister recall how publishers used to queue up in front of their house in a bid to get him to do the covers of their publications.

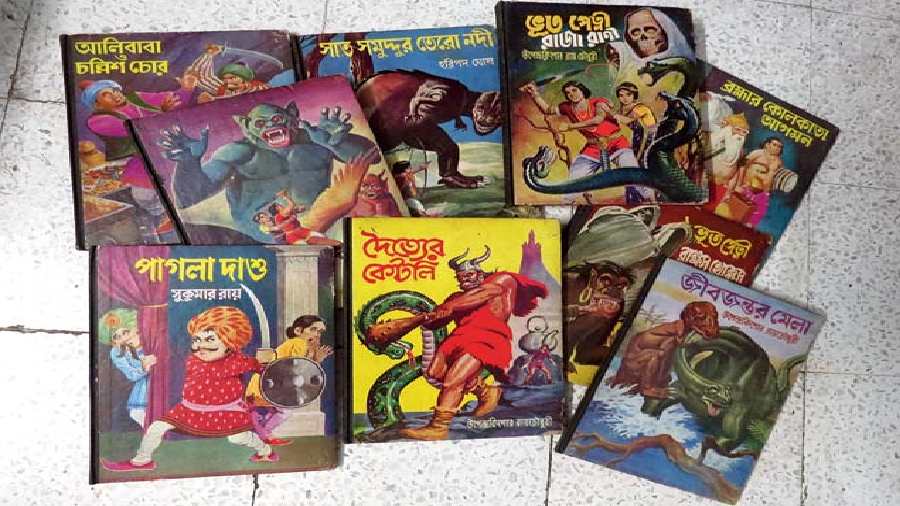

Indeed, my own childhood collection includes over a dozen titles illustrated by Debnath. These are large-format, hard-cover books with black cloth binding, typically ranging from 45 to 65 pages. Brought out by publishers like Narayan Pustakalay, Nirmal Book Agency, Basak Book Store and Kalpana Sahitya Mandir, they were priced Rs 3 to 4 in the late ’70s and ranged from compilations of ghost stories and folk tales to works of Upendrakishore Roychowdhury and Sukumar Ray to humourous tales by contemporary authors. While these are easy to ascribe because of the published credits, there are also sundry uncredited covers of normal-sized books of adventures and translations of English classics.

Among those confirmed as his brushwork by Debnath and collated in his complete works (Narayan Debnath Comics Samagra, for which he got the Sahitya Akademi award in 2013) are works of Hemendrakumar Roy, Sibram Chakraborty and Premendra Mitra, tales of Gopal Bhar along with translations of Jules Verne, Victor Hugo and William Shakespeare.

“Mahesh Agarwal of General Library once told me that after Narayan babu started to do the covers in place of Sailesh Pal of their Bajpakhi series, comprising Sriswapankumar (Samarendranath Pandey)’s stories of detective Deepak Chatterjee and assistant Ratan Lal, their sales increased tenfold,” says Ghosh.

Indeed, the dramatic and high-on-action illustrations in bright colours are so attractive that it is easy to see why the covers caught the eyes of teenagers and helped sell the books. “In 1971, Nirmal Book Agency brought out Bhoot Petni Raja Rani, a compilation of seven Upendrakishore tales. Thanks largely to Debnath’s cover, it became a huge hit, getting picked up as birthday gifts, prizes in competitions, for libraries... That started the craze for his covers.”

Nirmal’s competitor Basak Book Store, Ghosh says, soon prepared a catalogue of 50-60 book covers which had no mention of the authors or the price. “That’s what they showed to customers to secure orders. Most covers in the catalogue were by Narayan Debnath.”

Publishers, he adds, used to plan new titles or get translations done of classics just so they could get Debnath to do the cover, “just as scripts would be written in Bombay in those days keeping Amitabh Bachchan in mind as the lead”.

But once his work pressure increased with commitments to produce as many as four comic strips — writing the stories, planning the story board, doing the sketches and penning the dialogues — every month, the fourth being secret agent Kaushik Roy or Bahadur Beral for the Suktara cover, he had to step away from book illustrations.

One cannot but concur with Agarwal who had lamented to Ghosh that in Narayan Debnath, we lost a great book illustrator to comic strips.

A page from a Calcutta Chemicals ad.

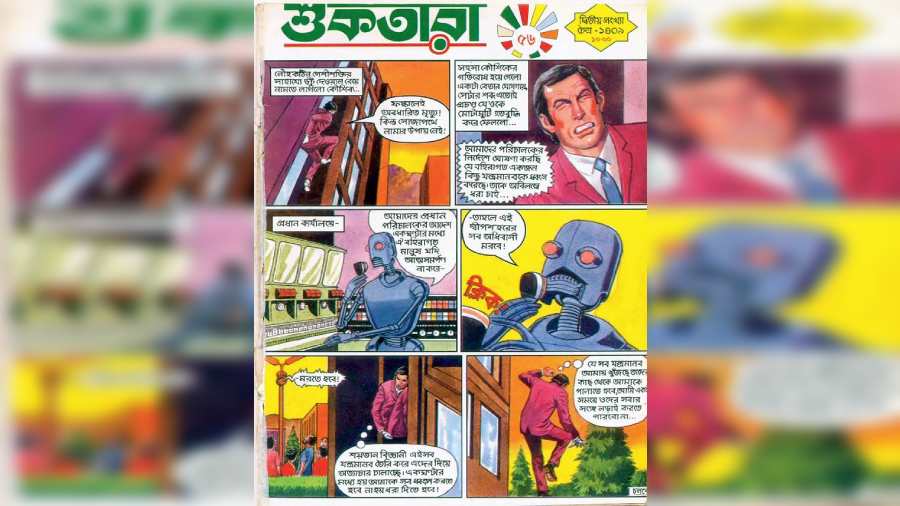

A cover page of Suktara with a Kaushik Roy story

A different start

Debnath may be known for his funny creations but he started his career with realistic sketches.

In an interview with Doordarshan, he recalls that he was paid Rs 3 each for the first three illustrations that were commissioned by Dev Sahitya Kutir in 1950.

“Narayan babu’s first choice was serious realistic sketch,” stresses Ghosh. In 1951, he started illustrating a Tarzan series for Suktara, with Sabyasachi (pen name of Sudhindranath Raha) as author, which he would continue till 1992 (barring seven issues illustrated by Mayukh Chowdhury, which were printed in Delhi due to labour strike in Calcutta). “One had to be an action movie and adventure story buff to produce such anatomically precise action moments year after year,” says Ghosh.

In several interviews, Debnath has spoken of his love for Dinendra Kumar Ray’s Robert Blake detective stories. “Even late in life, he used to devour Bruce Lee and Mithun Chakraborty action films on TV. As for Tarzan, his favourite actor was Johnny Weissmuller. His sketches bear resemblance to the swimmer-turned-actor’s physique,” Ghosh says.

Debnath may have been a soft-spoken man but he was adventurous at heart. In an interview, he recalls taking up a dare to dive from a height in the Hooghly as also swimming across the river and back, feats he used to see achieved by Hindi-speaking boys on the Howrah ghats but never attempted by his friends.

Ghosh, who was quite a Boswell to Debnath’s Dr Johnson in his late years, recalls retrieving a knife from his house. “This was one he had got a blacksmith to make, based on a sketch he had done after seeing a Tarzan film. It was not sharp enough to be of use but he would sling it by his side as he leapt into local ponds for a swim, Tarzan style, he had told me,” Ghosh says, laughing.

The Tarzan stories, with Debnath’s sketches numbering close to 900, were later compiled in books like Tarzan the Fearless, Tarzan the Apeman and Zambezir Ujane Tarzan.

Book covers illustrated by Narayan Debnath. Picture by Sudeshna Banerjee

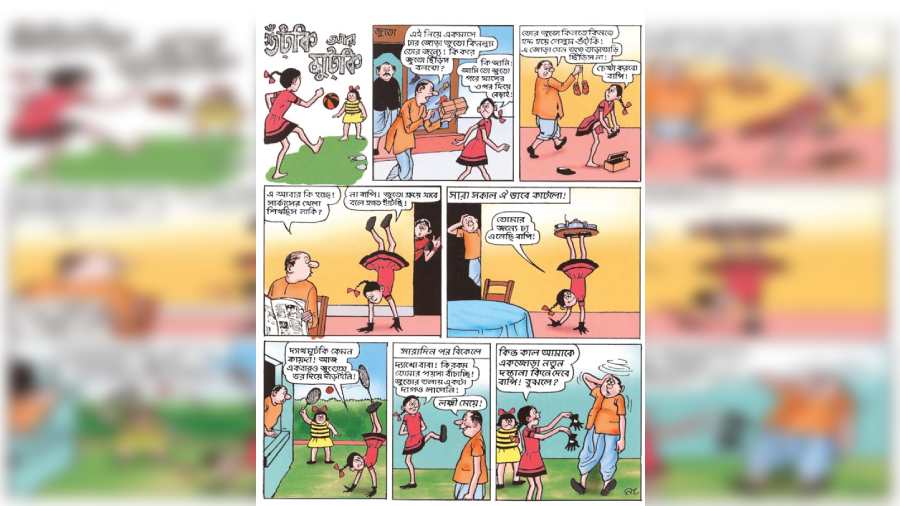

Shutki ar Mutki is possibly the only comic strip by Debnath with girls as title characters. It was short-lived as some women readers wrote to Suktara objecting to the names

Biography beckons

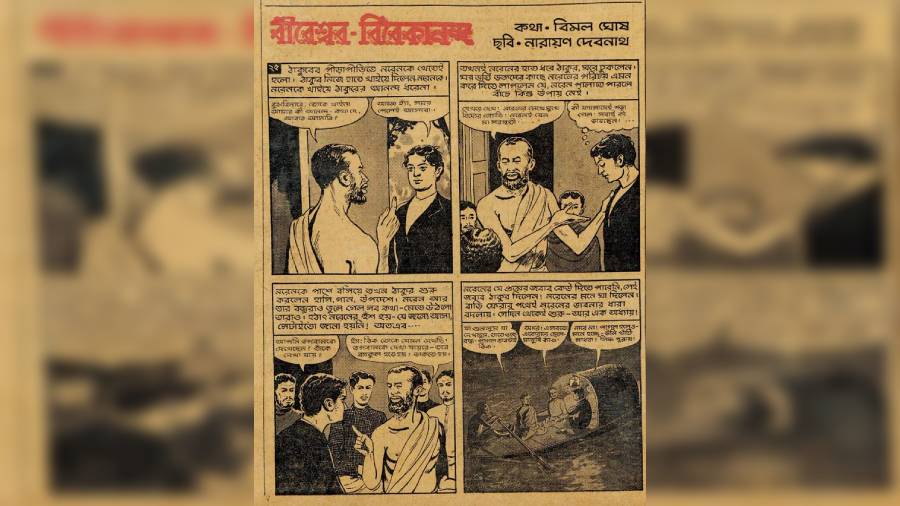

The central character of Debnath’s first comics series was not Handa or Bhonda but Rabindranath Tagore. On the occasion of the poet-philosopher’s birth centenary, section editor Bimal Ghosh, who wrote under the penname Moumachhi, commissioned Debnath to sketch Tagore’s life for the children’s page of Anandabazar Patrika, titled Anandamela, which came out on Mondays. The series was called Rabi-Chhobi and started on April 17, 1961. Ghosh provided the text while Debnath did the illustrations.

It continued for 50 weeks and ended somewhat abruptly on April 23, 1962 with Kadambari Devi’s suicide and Maharshi Debendranath Tagore rewarding young Tagore for his composition Nayan tomay payna dekhite in 1887.

This would be the first work of Debnath to be printed within two covers, by the Varanasi-based publisher Sarvoday Sahitya Prakasahani in 1962, in both Hindi and Bengali.

After Tagore’s life, the duo produced the life of Swami Vivekananda in 100 instalments printed from May 14, 1962 to January 18, 1965 in the newspaper, with the title Bireswar-Vivekananda, which was later changed to Rajar Raja. It was compiled as a book, titled Rajar Raja, by Ananda Publishers in 1965. On May 31, 1965 the life of Shivaji was started on the same page but abandoned after 35 instalments on February 28, 1966.

He also illustrated Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay’s Durgeshnandini for another Dev Sahitya Kutir publication, Nabakallol, around this time.

Skill for thrill

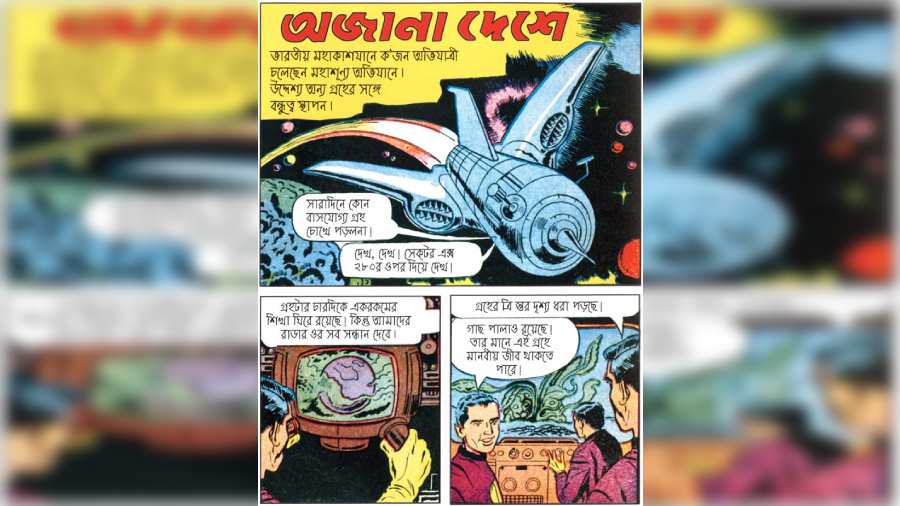

Despite the success of Handa Bhonda and Bantul the Great in Suktara, which fostered the birth of the equally successful Nonte Fonte in 1969 in Kishore Bharati, Debnath would strike fresh ground with three adventures printed in various Puja-special magazines — Ajana Deshe (1969), Mrita Nagarir Danob Debta (1973) and Duhswapner Deshe (1975) — with his watercolour illustrations. These are unconnected stories, dealing with a star trek by an Indian space ship, a lost world unearthed under the Sahara desert and an encounter with pre-historic creatures inside a dead volcano in Africa, respectively. Another mystery, Rahasyomoy Yatri, got serialised on the cover of Suktara in 1973 with an unnamed secret agent on a rescue mission.

But Debnath would create a central character in the thriller mould too. In 1975, seriaised on the Suktara cover, was born Kaushik Roy, quite a James Bond in his one-man transnational manoeuvres on behalf of the government’s secret service, but strictly minus the womanising. Roy’s steel right wrist made the spy a bit of a superhero too, with the wrist being able to shoot bullets, emit darts, release paralysing gas and serve as a wireless communicator with “headquarters”. Unlike the comic strips, the Kaushik Roy stories would carry on for several issues, and have a finite end to each adventure.

The debut, titled Sarporajer Dwipe, ran for 36 issues and was the first of 13 Kaushik Roy thrillers penned by Debnath.

The realistic illustrations for these adventures bear the influence of John Prentice’s sketches in the American comic strip Rip Kirby, which he used to cut out from the pages of Anandabazar Patrika for his scrap book. “You can see the use of crosshatching as a technique for light and shade (use of parallel, intersecting lines to shade an illustration) and in the folds of drapery which he picked up from Prentice,” Ghosh says.

Another detective series illustrated by Debnath was Black Diamond, on the exploits of Indrajit Roy, which appeared from April 1970 in Kishore Bharati. The stories were penned not by him but by Dilip Chattopadhyay, the magazine owner’s elder son.

A sci-fi story in comic strip

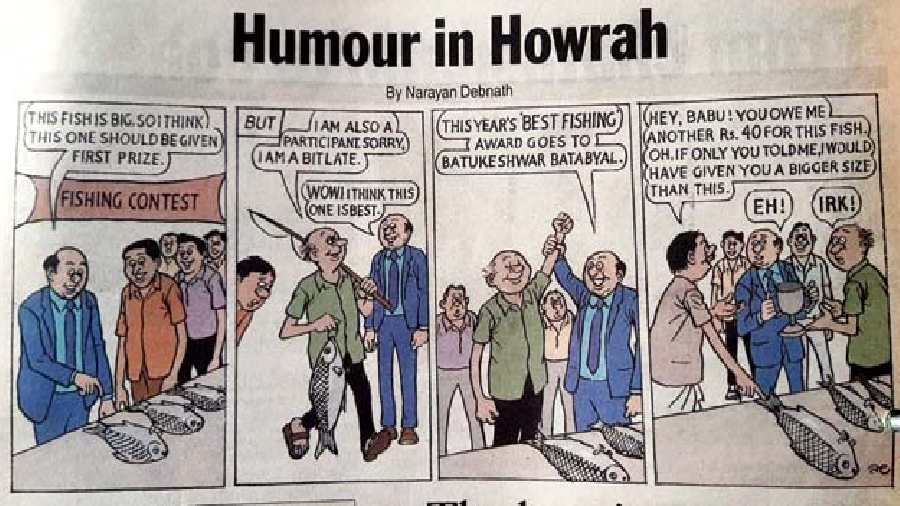

A comic strip produced by Narayan Debnath for The Telegraph Howrah. Courtesy: Dalia Mukherjee

From the Anandabazar Patrika archive

A sci-fi edge

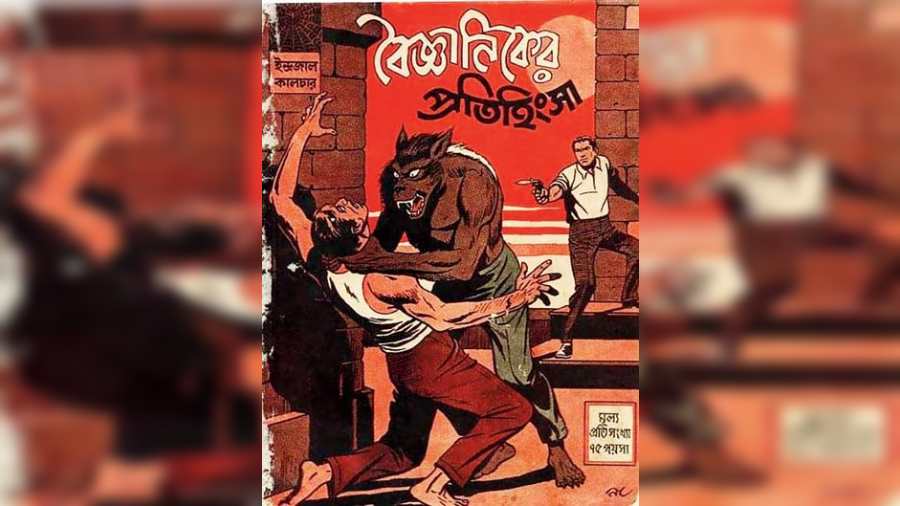

A prize addition to a volume of Kaushik Roy adventures, brought out by Deep Prakashan, which currently holds the copyright to Debnath’s works, is Baigyaniker Protihingsha. This is a work of science fiction, not linked to the secret agent, that harnesses a European metamorphosis lore. The story is of a obsessed scientist turning to a werewolf every night by injecting a potion of his own invention. “It was Debnath’s single contribution to a series of four books published by a local Howrah publisher. He had forgotten about it. I chanced upon a copy on eBay (an online e-commerce site) and purchased it at a premium,” said Ghosh.

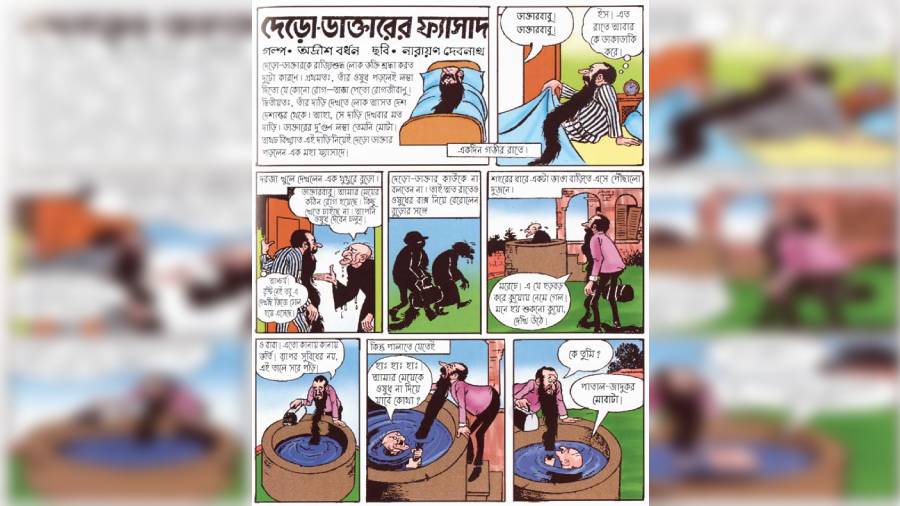

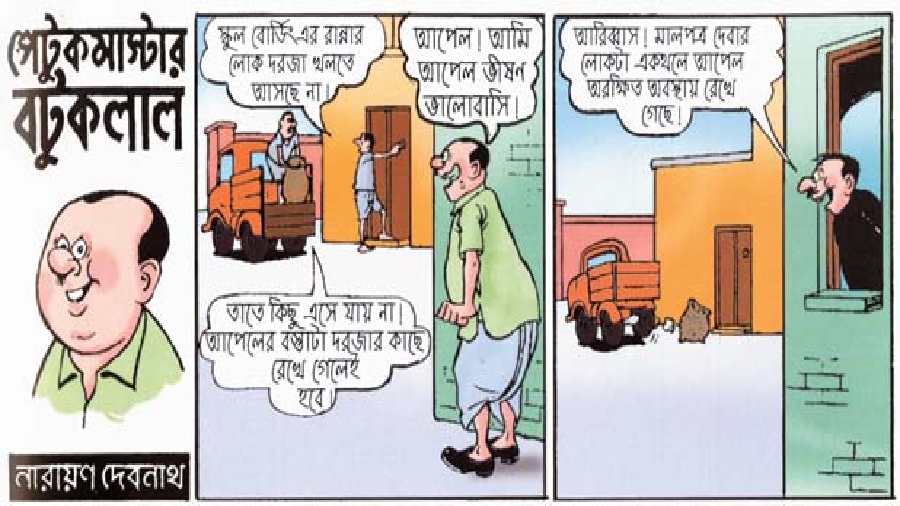

Talking of sci-fi, Debnath had also collaborated with Adrish Bardhan, possibly the best-known science fiction author in Bengali. The collaboration was brought about by Calcutta Chemicals to produce a series of advertisements for their Benzytol soap, published in Suktara and Sandesh. The collection Chhobitey Mojar Golpo, published by Deep Prakashan, which includes numerous funny strips by Debnath with lesser-known characters, includes three such advertisements. These are delightfully creative specimens that span 12 to 16 panels over two pages, with characters like Dero (bearded) Doctor, Patal Jadukar (wizard of the nether regions) Mobata and Petnirani, all having their problems resolved with a bar of the soap that cures skin and digestion ailments at the end of each story.

Post-script

Debnath had a fine singing voice. Asked in an interview what he would have become, if not a comics artist, his reply was “a musician or a bodybuilder”. He would work out at a gymnasium behind his school, BK Paul’s Institution, in his youth.

Given that he has left behind a stupendous body of work that holds generations of children in Pied Piper-like thrall, his crow quill nib has achieved those ambitions too through its deft strokes.

Did you know?

Narayan Debnath drew the title cards of films like Jeeban Trishna (1957), Swaralipi (1961) and Kamallata (1969).

His first earning as illustrator at Dev Sahitya Kutir was Rs 9 for three sketches.

Nonte Fonte was inspired by Satyen Bose’s 1949 film Paribartan (Jagriti in Hindi), which was set in a boarding school and had two prankster friends and a superintendant. The film later became a book that was illustrated by Debnath. He took just the setting, not the story.

He produced many strip cartoons used typically as fillers at the end of stories. About five such were created in 2008 with English text for The Telegraph Howrah, a community news supplement circulated then in Debnath’s hometown.