If you enter the University of Calcutta campus through the College Square-facing gate, you will find the Central Library on your right and a majestic ivory-white Asutosh building on your left. When you enter it, you can either take the elevator to the first floor or walk up a flight of stairs. Leaving the stairwell behind, you can walk towards the Department of Languages and Literature, and pass by huge classrooms named after eminent Bengali writers. Meandering through never-ending hallways, and after the correct combination of right-left-right turns, you will find yourself in front of room 221, the office of Mrinmoy Pramanick, assistant professor and head of the university’s department of Comparative Indian Language and Literature (CILL).

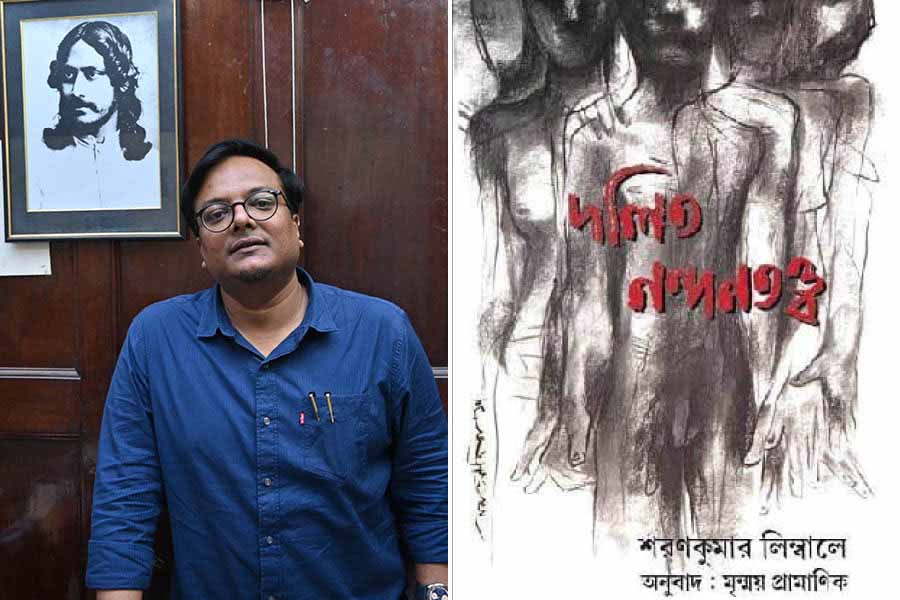

Pramanick’s most recent title is that of the winner of the 2023 Sahitya Akademi Award (announced on March 11) for Dalit Nandantattwa, a Bengali translation of Dalit Sahityache Soundharya Shashtra (in Marathi) by Sharankumar Limbale. My Kolkata caught up with Pramanick at his CU office to discuss his reaction to the award, the challenges of translation, who should write Dalit literature, and more. Edited excerpts from the conversation follow.

My Kolkata: Congratulations on your Sahitya Akademi Award. What does it mean for you to win it?

Mrinmoy Pramanick: Thank you. Firstly, it came as a huge surprise! It means a lot to me because I didn’t think of winning it. This book is my first work. It was released by Limbaleji and Nabaneeta Dev Sen. And now, in the same year, both Nabaneeta Dev Sen (posthumously awarded for the English translation of Chandrabati’s Ramayan) and I have got the translation award!

It was 4.19pm on March 11 when I got a call from the Sahitya Akademi. From then till 1am, I attended calls from students, colleagues and well-wishers from all over the country. I realised then what this award means. It is also a huge encouragement, since I have just started my academic career.

‘I had known Dalit literature to be translated widely, but not in Bengali. That was the turning point of my academic life’

How did you decide on translating Dalit Sahityache Soundharya Shashtra by Limbale?

When I was doing my research for MPhil and PhD at the University of Hyderabad, I found the English translation of this book by Limbale. Hyderabad has a comprehensive curriculum across various departments on Dalit literature, and several student organisations espousing Dalit ideology. This environment fosters a Dalit consciousness on campus and, you could say, I got my consciousness about Dalit literature while working at the university.

In 2009, when I had joined as an MPhil scholar, I was introduced to this book. I found my co-supervisor, Tutun Mukherjee, had a collection of Bengali Dalit literature. I had known Dalit literature to be translated widely, but not in Bengali. That was the turning point of my academic life. I realised I should translate this book into Bengali. Fortunately, I had a mandatory language learning course in my degree where Marathi, Khasi and Sanskrit were offered. I chose Marathi. Soon after, coincidentally, Limbale visited the university. I met him and told him that I want to translate his book into Bengali. He told me: “None of my books has been translated into Bengali. So, if you translate this, I’ll be very happy. And immediately, I’ll transfer the copyright, so you can go ahead.” That’s how I started working on the book.

‘I proceeded with the Hindi translation, but I always kept the Marathi text beside me’

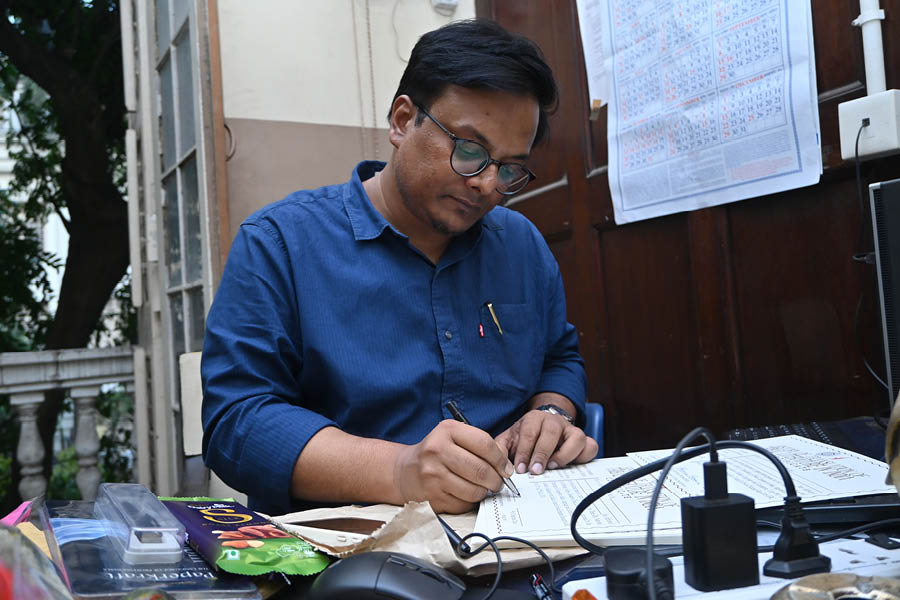

Pramanick frequently consulted Limbale during the translation pro Amit Pramanik

Can you talk about your process of translation, how long it took you to translate and produce the final manuscript? Also, what sort of challenges did you face?

It took almost four years. I first came across the book in 2009, started translating it in 2013, and ultimately published it in 2017. So, it has been a long journey. As I learned Marathi, I was very passionate about translating it from Marathi, so I initially started with the original text. But I realised that the critical language is very different. And it’s not only about learning a language, it’s about having a hold on the critical language. I started working on translation, and I often used to talk to Limbaleji about it. He suggested I consult the Hindi translation: “You can take help of this link language because Hindi and Marathi are very close to each other. It’s also a very faithful translation. And as you have already learned Marathi, you’ll be able to read the Marathi text.” So I proceeded with the Hindi translation, but I always kept the Marathi text beside me. If you see my translator’s preface, I have tried to locate the text both in the Marathi and Bengali context, to convince my Bengali readers why reading such a text is important.

About difficulties in translating — because of the shared roots of Bengali, Marathi and Hindi in the Vedic language, challenges arose. For example, Tatsam words, words borrowed directly from Sanskrit, sometimes have a common meaning across languages. We use the word bhaat in Bengali and also in Marathi. However, the meaning of the Tatsam words also varies across languages. Like the use of satta. Satta in Marathi is power, right? It also comes with a Buddhist philosophical connotation. But satta in Bengali is the inner soul. The word anubhav denotes experience in Marathi, but it means to feel something in Bengali. There are many such words. Translating them became difficult, at times. Hence, it took a long time to edit my draft.

‘People are interested in listening to voices which have been unheard’

In the last decade, there has been a sort of explosion in Dalit studies and the writing of Dalit literature. What do you think is the reason behind this growing interest?

There are multiple reasons. English literature as a discipline has been in serious crisis for the past six decades. The English discipline has moved towards not only Indian writing in English, but English translations of Indian literature. The English discipline is moving out of the Anglosphere and into North American literature, then Latin America, Africa, the global South, Southeast Asia, right? Simultaneously, English publishing houses have started to dig into various languages to translate their literature as these represent new economic, intellectual and creative zones. People are moving towards marginal literature because people are interested in listening to voices which have been unheard.

Who gets to write Dalit literature? A question of empathy versus sympathy

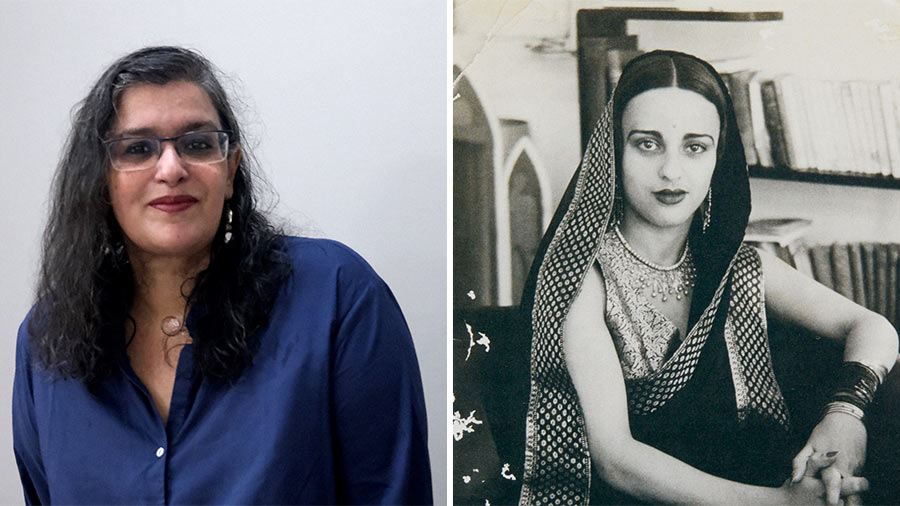

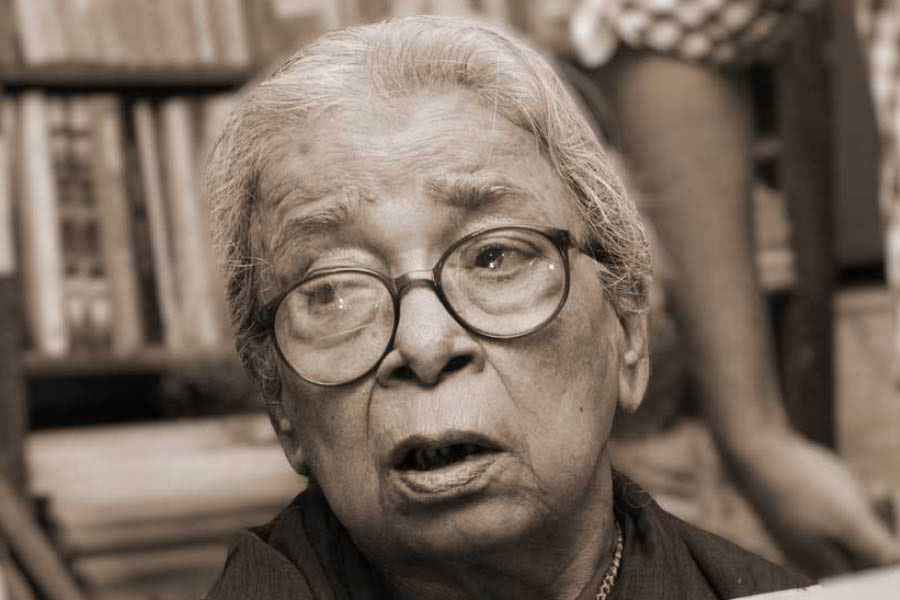

Pramanick cites Mahasweta Devi as someone who has impacted Dalit literature without being a Dalit herself TT archives

It is believed that Dalit literature is inextricably intertwined with the identity of the Dalit person themself. In that case, do you think a non-Dalit person can write Dalit literature?

This has been a long debate among Dalit scholars and literary practitioners. They always argue that only a Dalit can write Dalit literature because Dalit literature is a literature of empathy. It’s a literature of lived experience, of humiliation, of reclaiming one’s space in history, tradition and national spaces. It’s about emancipation of the whole community. If non-Dalit writers write Dalit literature, then it will be full of sympathy. There won’t be any lived experience either.

But the thing is non-Dalits have also played a crucial part in building the Dalit consciousness. For example, Mahasweta Devi wasn’t a Dalit. But the kind of literature of resistance she wrote is well accepted by Dalit scholars and activists. The writing and thinking of non-Dalits is also very important. However, even in this, there’s politics. If I say, non-Dalits can also write Dalit literature, then the generic space of Dalit literature will be occupied by them. Because non-Dalits have all the cultural, intellectual and financial capital. They have a polished language and strong vocabulary. So the space shouldn’t be wholly occupied by the non-Dalits. Dalit literature, therefore, must be the literature written by Dalits on Dalits. Otherwise, voices of the community, along with their histories, will be lost.

At the beginning of your book, you have included a translated excerpt of Rohith Vemula’s suicide note. In the last few years, there have been several instances of institutional deaths of Dalit scholars. Do you think that this constant increase in Dalit studies has the power to change the current situation in which Dalit scholars are studying in universities of national repute?

Dalit literature and studies play a crucial role in developing consciousness about marginalised sections of people. After getting acquainted with Dalit literature, I introduced it in our curriculum at Calcutta University. So, yes, it develops an intellectual influence among people. However, there are Dalit students not just in the arts, but also in other disciplines. Dalit people in our country belong to lower economic groups. They face challenges in higher education, particularly with language barriers and an elite academic environment. Afraid to speak up, they feel humiliated and isolated, which results in their deteriorating mental health, which often leads to suicides. I believe that constant counselling is required not only for marginalised students, but also their peers and educators. I also believe that the government should launch more welfare schemes to facilitate public education institutions, where students from various backgrounds can mix with each other, which will promote inclusivity and understanding among individuals.

‘Translation, as a course, should be incorporated across disciplines throughout all educational institutions in the country’

Pramanick has three books coming up, including one involving children’s literature Amit Pramanik

As a translator, what are your upcoming projects?

I’m currently working on a book by the Khasi poet, Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih, titled Yearning of Seeds. I have also translated selected critical writings from Bengali Dalit literature for publication. There’s a third interesting book, Chhoto Der Totopara. This will be the first printed children’s literature of the Toto community. And, more interestingly, this literature is solely written by children. This will be published soon.

‘I consider translation as one of the most powerful tools of peacemaking’

Any final thoughts on the importance of translation?

I think translation, as a course, should be incorporated across disciplines throughout all educational institutions in the country. Translation, as a culture, can make college and university students better citizens of a country like India. I also consider translation as one of the most powerful tools of peacemaking, as it initiates conversation among the communities crossing all kinds of boundaries. So, translation should be perceived in that way. And whatever translations we’re doing, all these are small contributions towards a larger project of expanding our cultural inclusivity.