Can trauma persevere through generations? This question has been central to Janam Mukherjee’s life. It weighed upon his chest during an anarchic childhood in Michigan, and came with him as invisible baggage when he arrived in Kolkata, searching for his roots. It drives his perspective while teaching history at Toronto Metropolitan University, and peeks through the lines when he writes about the impact of riots and famine in Bengal. This is his story, and much more.

Navigating familial trauma

Janam’s story doesn’t start with his birth in 1967, New York City. It began almost three decades earlier in the 1940s, when Kolkata was caught between the Japanese and Allied forces. His family’s house was in Mominpur, right in line of the attack. “When the docks were bombed, the house shook and its foundation cracked. At 10, my father experienced bombing like people from Yemen and Gaza do today.” Like many others, his family fled back to their desh on the other side. “Those days in Bahadurpur (in today’s Bangladesh) were the few childhood memories of happiness and peace my father ever had,” said Janam Mukherjee when speaking to My Kolkata at his home in Tollygunge, where he spends two months every year.

Janam Mukherjee, author of ‘Hungry Bengal’, at his house in Tollygunge, where he spends two months every year

The Bengal famine followed, and Janam remembers hearing stories about people lying dead on the streets. It was the Calcutta Riots of 1946 though, that would inflict a wound on his father, Kalinath Mukherjee, that he would struggle to hide for the rest of his life. A mob had killed all the men in their adjoining house, and turned to them. “My jetha (father’s older brother) rounded up the family and fled to the rooftop, locking the door from inside. The mob set the house on fire, and my father saw the family cook, someone he had known his entire childhood, getting beheaded. Finally, my jetha found an old rifle and fired. The crowd dispersed and the fire brigade rescued the family,” recounted Janam. Throughout his life, Kalinath had nightmares about the bombings and riots. He would complain about a weight pressing upon his chest, and call out for his mother.

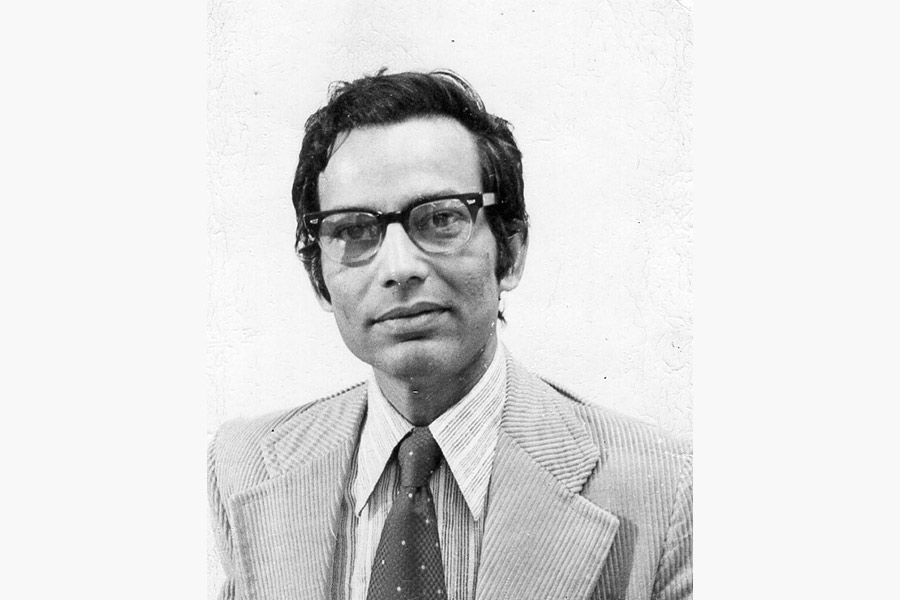

Janam’s father Dr. Kalinath Mukherjee in 1959, shortly after moving to the USA

The displaced family sought refuge in the Rashbehari Gurudwara and tried to piece back their life — 30 people lived in one room, before moving to a dilapidated warehouse in Kalighat. Janam’s jetha assumed the role of the provider, and through scrapes and bruises, put food on the table. His father studied metallurgical engineering at the Bengal Engineering College (now IIEST Shibpur), and left for the US in 1956.

New beginnings in America

A 13-year-old Janam fishing with his father in Michigan

At the University of Illinois, Janam’s father met his mother while completing his PhD. She is of Irish-Hungarian descent, and was a product of similar familial struggle. “Her family came to Chicago in the beginning of the 20th century, and worked in factories, slaughter houses and truck yards. She was the first from her family to go to college,” said Janam. Kalinath got a job as a metallurgical engineer, while she taught English at a community college. They got married in 1959.

Despite it being the 1950s, there was no friction between their cultures, largely because Kalinath didn’t carry Bengal with him to the US. He had left Kolkata with a one-way ticket and an old suitcase. It broke open at Heathrow airport, but he had to keep moving. In a swift motion, he cut his poite (sacred thread) and wrapped it around his suitcase, never wearing one again. “It felt like [he was] forgoing this identity he had, using it as a right of possession towards a new identity.”

The only knowledge Janam had of Kolkata was through a few of his father’s stories about loss. “His mother and didi died while he was in the States. The only Bengali I heard was through these trunk calls to Kolkata. There would be two minutes of shouting, offers to send money for the funeral, followed by my father weeping, as the line went dead. Growing up, I thought Bengali was a language that people mourned in.” Janam was raised American, and had little interest in his Bengali heritage.

Janam’s parents (seated), with his family in Kolkata

The ‘racial other’

However, he was also very proud to not be white, having grown up around white supremacists. Apart from hearing racial slurs throughout school, he also read extensively about Black nationalism, and was inspired by Eldridge Cleaver and Malcolm X. He remembers how the feeling of being a ‘racial other’ drove him to anarchy.

After school, he joined the University of Michigan. But the rebellion within hadn’t died. “One night, I struck up a conversation with a young man from Michigan. We spoke about Allen Ginsberg and Charles Bukowski, and the meaning of freedom. The next morning, both of us dropped out from college.” Both of them were 18, with just $1000 in their pocket. In order to make ends meet, they began labouring in trucks and factories, saving enough to travel through freight trains and hitchhike through the US.

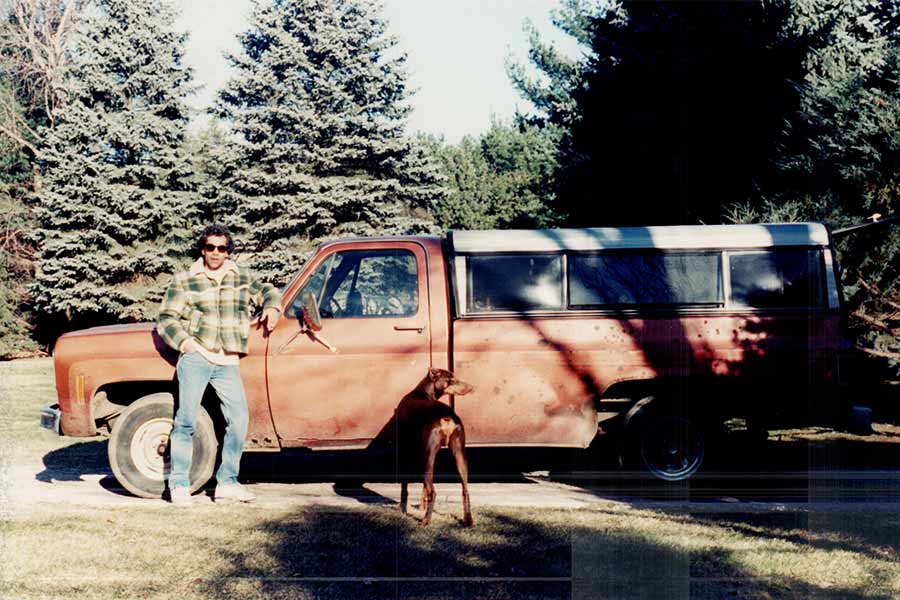

Janam and his dog Drake in Alaska, in front of a truck the author lived in for a year and a half while travelling during 1993-94

By his own admission, Janam had “given up all structures of society” by his mid-twenties. “I had left college, was sustaining through manual labour, and slept in the open more nights than I can count. I travelled like this throughout the US and Europe, but there was tremendous rage within me. I began thinking about those riots and my father’s broken identity.”

By his late-twenties, he knew that he needed to explore his father’s roots to better understand himself. Two incidents during this period proved pivotal to his politics.

While working as a delivery van driver in San Francisco, Janam was asked for his ID by a cop. He felt racially profiled, and declined. Within no time, he had been handcuffed and taken to the police station, where he was detained for 36 hours. “It was my first time in jail. You have to experience it to know what it is. If you believe in personal freedom, when that door shuts, your entire soul will rebel.”

The second time he was arrested was in 1999. He was building swimming pools in Michigan, and making great money. By then, he had cemented his plan to go to Kolkata, even buying a one-way ticket, just like his father had in 1956. On July 4, thousands of people were walking towards the riverfront at Lansing, MI, excited for the firework show in honour of the USA's independence. Janam was there with his friends, excited about a new beginning in a new country. He was supposed to fly out on July 14.

Janam Mukherjee in New York City in 1987

“My eyes met with two jacked cops. They walked up to me and asked for my ID. I declined. One of them slammed me to the ground and handcuffed me. His partner put his foot on my back, driving my face into the pavement. All the way to the police station, I furiously asked what I was being charged with. A cop shoved me inside the jail cell and shut the door, proceeding to beat me up. It is one thing to be jailed. It is another to be brutalised in jail, because they can kill you. My clothes were torn, and I felt completely naked,” said Janam recounting the ordeal.

Janam’s girlfriend at the time paid the bail. When he was summoned by the court, he wrote a letter detailing his plans in Kolkata, but to no avail. He finally left the US on July 14, unsure whether he was a felon. “I didn’t know if I would be able to see my jetha. I kept wondering if I would be pulled up at Dum Dum on the charges of fleeing the US. Thankfully, my then-girlfriend explained my situation, and got them to waive the charges.”

Back in Bengal

After years of planning, he finally arrived in Kolkata at the age of 32. Even though he couldn’t speak the language, he felt an instant connection. “From the chaotic buses to the extreme humidity, there was this anarchy of life, for which I felt at home. I almost feel bad for people from Kolkata, because they can never experience what it is to set foot here for the first time.”

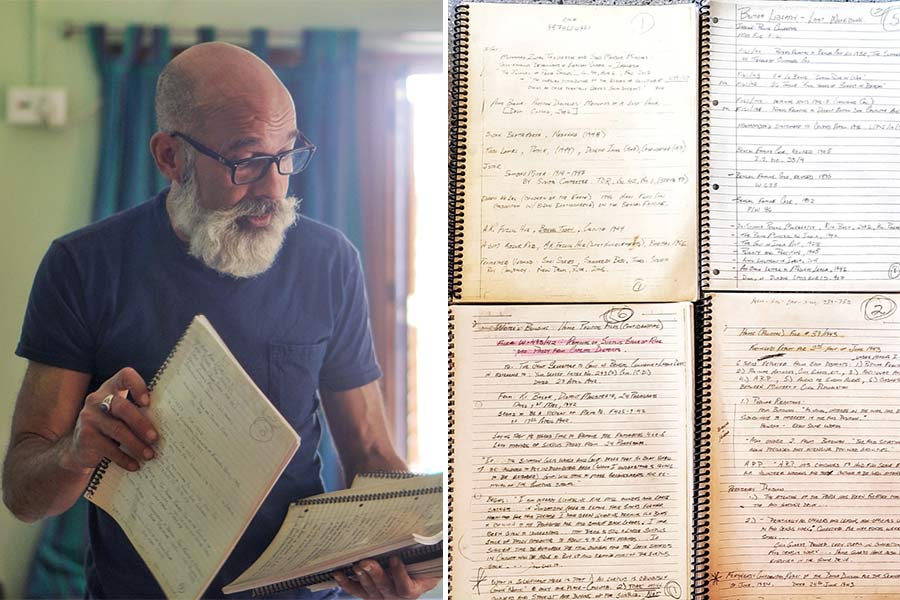

Janam left Kolkata with meticulous notes from the city’s archives, and descriptive journals from two years of interviews

Janam’s first few weeks were rough, and his inability to speak Bangla didn’t help. Gradually he figured out a routine, where he would study Bangla for five hours every day, read acclaimed Bengali writers, and speak to the elderly in his locality about war and famine. “It took me weeks to spot a muddy path behind Lord’s More, which opened up to the bazaar. Till then, I had nowhere to get groceries from. My jetha was also very concerned about my safety and didn’t want me to go to mishti shops to talk to random people. I couldn’t see through the chaos without linguistic skills.”

Janam also noted a difference in the definition of identity. “My name has always indicated foreignness to people, and my teachers always called me Jami. In Kolkata, for the first time people called me Janam.” All his life, he had been a brown person in the US, susceptible to being harassed by the police. Here, he was a Brahmin with the surname, ‘Mukherjee’, and was treated differently everywhere. “I was horrified by the social barriers brought in by caste, where people working in my house wouldn’t even drink from my glass.”

L-R: In Kolkata, a young Janam with his (right) ‘jetha’ and the family, and his ‘jethima’, who along with his ‘jetha’, kept the family together and raised his father after the riots

For two years, Janam interviewed a variety of people on the impact of war, the Bengal riots, and the famine. In 2002, he decided to seek funding for the project, and returned to Michigan to complete his degree, armed with journals documenting his time in Kolkata.

Return to the US

Right off the bat, he immersed himself in coursework, taking 25 credits. Fate wasn’t done testing Janam yet. His father, who had been suffering from Parkinson’s, experienced a drastic decline in health, and had to be admitted to the hospital. Every night, he would take his books and computer to the hospital, and work by his bedside. To this day, Janam is haunted by how rapidly his father was cast aside, once he wasn’t useful to the system. “He worked for the United States Industrial Military Complex, who used his skills to make weapons to bomb non-white civilisations. It is ironic, given that his own childhood was taken away by imperial power and war. And now he was no longer American, just a crippled old foreigner. They tossed him like a used pen.”

At the height of his father’s illness, Janam remembers his Kolkata visit being a happy time

Within a few months of starting college, his father passed away. It has been over two decades, but Janam continues to question his father’s identity. “Was he drawn by the value of the American Dream, or pushed by the trauma of the past?”

By 2006, Janam had cleared his undergraduate programme and received funding for seven years to complete his book. He became a Fulbright fellow in 2009, and got a PhD in Anthropology and History from the University of Michigan. He went on to become a post-doctoral fellow at Yale University.

It’s hard to believe the magnitude of Janam’s experiences. He sums it up perfectly, “Life is quite interesting. I got into Yale from the jailhouse of Lansing by researching archives in Kolkata, with money I made by digging swimming pools.”

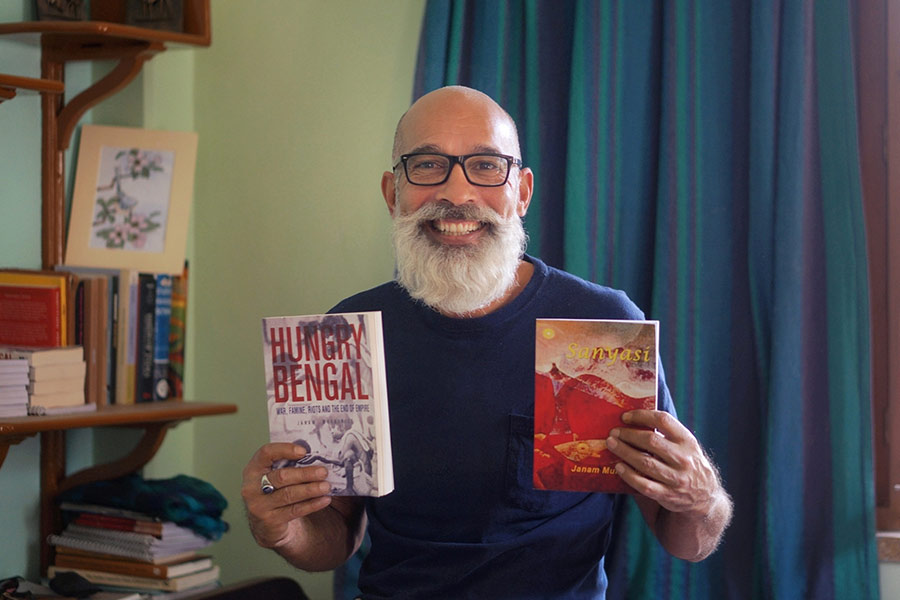

Janam’s entire life has been spent in the pursuit of writing. His books (L-R) 'Hungry Bengal' and 'Sanyasi'

He finally completed his dissertation in 2011, a massive combination of personal experiences, conversations, and histories. The historical aspect was published as Hungry Bengal: War, Famine, Riots and the end of Empire. Most of the dialogue on 1940s Bengal revolved around the Partition. The book has brought attention to the political and communal impact of the war, which had largely been ignored. Janam also terms it as an study about intergenerational trauma, peppered with his experiences of coming to Kolkata. “So much is communicated through gestures, sighs and tears. I question if it is possible to reconstruct our parent’s stories from these interpersonal fragments. Personally, I believe I was born with some memory of the riots.”

Much of the book also reflects Janam’s politics around the US. “I write about the policing of society and the use of emergency rule, both of which contributed to the famine. This book was written at a time when people were being tortured in Guantanamo Bay, and when Baghdad, a city of two to three million children, was being bombed by my country. Every time the United States bombs a non-white civilisation, I think of my father.”

Kalinath Mukherjee’s memorial in Kolkata

Intergenerational stories, across geographies

Considered one of the global experts on the Bengal famine, Janam recently contributed to a five-part documentary series by BBC Radio 4, titled Three Million. The show, which premiered on BBC World Service on March 2, explores the tragedy with depth that mainstream media hasn’t shown before.

Janam tries to bring the same empathy while teaching at Toronto Metropolitan University today, where he has students from war-torn areas around the world. He teaches courses on oral history and colonialism, with the aim to conduct radical conversations. “For the oral history project, most students end up interviewing family. The stories that I alone on the face of this Earth will know are amazing.” He added that colonisation is psychic, and students whose parents came from former colonies continue to harbour self hatred in their minds.

Currently, Janam is compiling his life’s work in a 700-page chronicle. The text traces his family history, from the Kolkata bombings and his father’s immigration, to his arrival in the city, and eventual return to the US, only to see him die. “It’s a blend of individual and intergenerational stories, across geographies. I probably won’t publish it because it’s too personal.”