There isn’t just one thing you notice, and remember, about Uma Sondhi Ahmad when you meet her; there are several.

For me, it began with discovering that she knew my grandmother and had taught my mother in school, and — much to my mother’s delight — that she remembered her former student. (As it turns out, ‘Uma Miss’ was, unsurprisingly, a favourite among the girls at Loreto House.)

Then, I noticed what a vision she makes. As she walked, slowly, towards her white bamboo chair in the verandah of her beautiful home in south Kolkata, Uma Ahmad, at 90 years of age, with her alabaster skin, pillow-white hair, black-and-white saree and a string of pearls around her delicate neck, radiated an almost ethereal, elf-like beauty — the calm, serene luminosity of one who has borne worlds and multitudes within her.

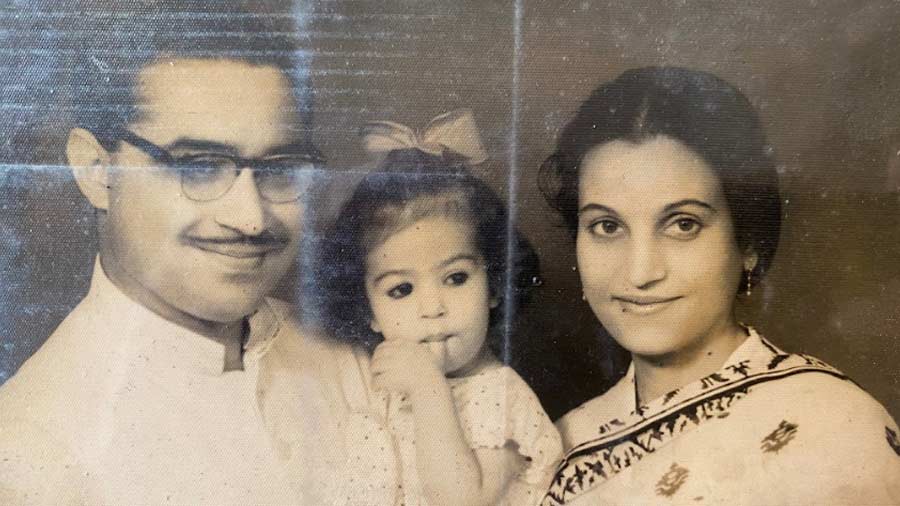

Uma Sondhi with her parents, Ved Pal Sondhi and Vidya Sondhi, in London, late 1930s

And she has. Here was a woman who had witnessed, and lived through, World War II, India’s Freedom Struggle, and Partition. In her nine decades of life thus far, she has resided in Burma, Jullundur (as it was known in British India), England, Lahore, Mussoorie and, of course, Kolkata. The expanse of her memories would naturally be immense – unfathomable, even, to someone hoping to, at the very least, scratch the surface. And those of us with parents, grandparents and friends in their sunset years know that we are racing against time to gather the stories of their lives, before a critical segment of our histories – national, familial, personal – is gone forever. How does one gather it all?

But the glimpse that Uma Ahmad gave me into her life, over the next couple of hours, put my mind at ease. There is, after all, no way to fully capture the vast swathes of the lived experiences and inner worlds that make up a human life. Nor is there any need to. Even in the imparting of oral histories, countless memories will slip through the cracks, and that’s alright — the fraction that we may have the good fortune to access, glean and preserve is, in itself, priceless.

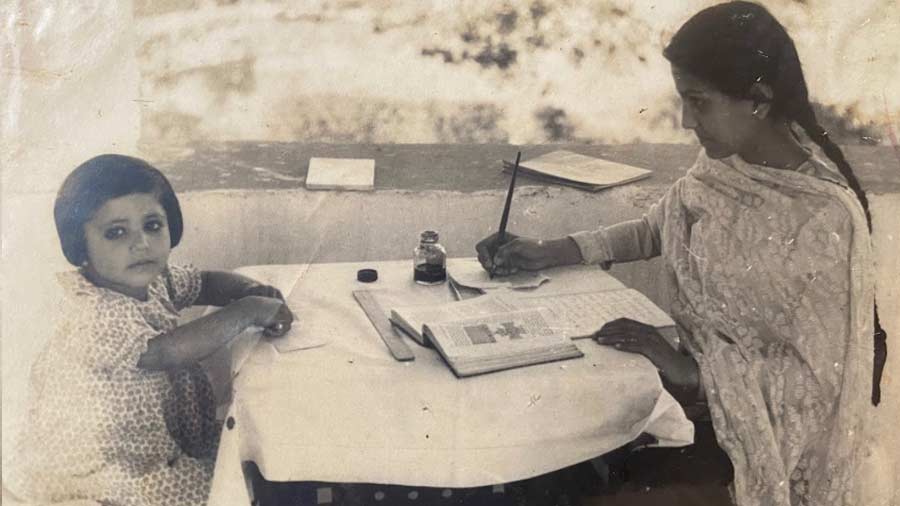

Uma (right) with her sister, Ruma, in Lahore, 1944

‘I remember the tension as the boat docked at Karachi’

This is what I saw, and, therefore, noticed the most, about Uma Ahmad: her deep intelligence and the softness of her memories — both those that she recalled on her own, and those that lingered just outside the contours of her recollection… the latter seamlessly augmented by her daughter, editor-author Anjum Katyal. Born in 1931 in Jalandhar to Vidya and Ved Pal Sondhi, Uma Sondhi was about five years old when she enrolled in Calcutta’s Loreto House, in 1936. Her first stint there was short-lived. The same year, Vidya and Ved Pal set sail for England with their children; and there they would stay for the next few years, living through the unnerving build-up — “the dreadful feeling of something coming” — to the Second World War.

In 1939, in the tense wake of the Munich Pact and right before the war broke out, the family managed to return to India. “I was very young, but I remember the tension that my parents were feeling as the boat docked at Karachi,” she recalled, her brow furrowing ever so slightly. With her soft voice and the practised skill of one who has taught history for years, she painted a picture of an undivided India that now exists only in the memories of those in their twilight years. “From there, we went straight to Jalandhar, where the whole family was waiting anxiously.” How did it feel to return to her place of birth? “I was very embarrassed!” she exclaimed, her voice suddenly taking on the lilt of laughter. “I spoke English with an English accent, and they used to start laughing!” Her devout, traditional mother and grandparents spoke to her in Jullunduri Punjabi, reacquainting the young girl with her mother tongue. Eight decades later, I sit across from her, listening to her talk to me in a voice of the past, unconsciously interspersing her pristine English with the melodic rhythm of her native Punjabi.

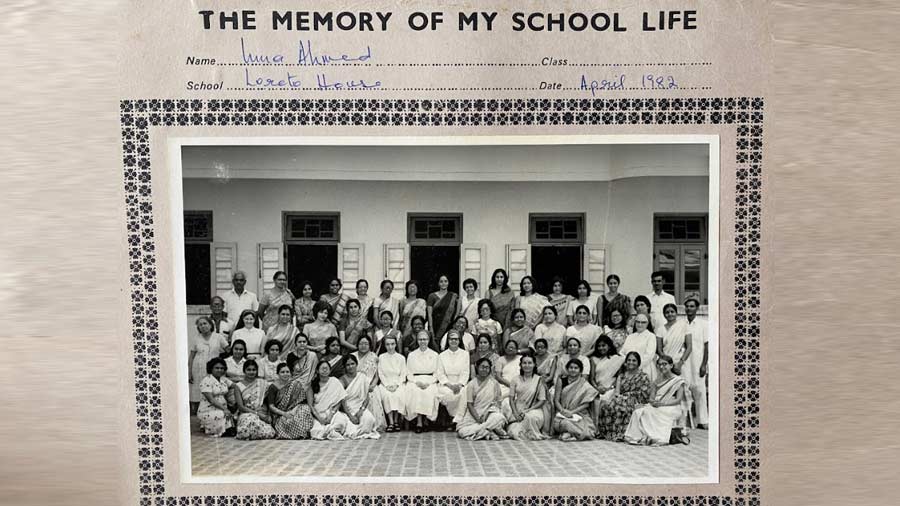

A faculty portrait taken at Loreto House, where Uma Ahmad taught history

In the years that followed, her life would go on to transform, periodically and exponentially, several times. She would come back to Calcutta and re-enroll at Loreto House in 1942, at the time of the Quit India movement. When the Japanese were going to bomb Calcutta, she would move to Lahore, as her father, an officer (later, Director General) of the Geological Survey of India, was transferred there. In Lahore, she’d study at the Sacred Heart Convent, learn about the Freedom Movement, and navigate the concept and practice of patriotism in her own ways.

“Being drawn into the struggle for Independence was not optional for us,” she recalled. “Initially, it was hard for us to comprehend everything that was going on. But Gyan Chand Sondhi, my father’s older brother — and a lawyer and freedom fighter who was frequently underground — explained it all to me. I remember that my beautiful silk frocks were tossed into a bonfire, and we all wore khadi.” She paused for a second. “It itched like anything! My poor mother had to get mulmul for the kameez!” Their acts of resistance branched out in other small but incredibly brave ways: such as not standing up for the British national anthem in a cinema hall. “There would be soldiers in the hall,” she almost grimaces. “We were scared, but we did not stand.”

Partition would shape itself into reality, and, in 1947, she’d return to Calcutta, pursue a Bachelor of Arts degree at Loreto College, graduate in 1951, and join the advertising department of B.N. Elias’s National Tobacco Company the following year.

Uma and Mumtaz Ahmad

Love, humour and desi food

Soon after, she’d meet Mumtaz Ahmad, whom she’d go on to marry and have three children with. She’d become a beloved teacher of History, and join the TTC (Teachers Training Certificate) faculty at Loreto part-time; she’d become a grandmother, and also serve on the West Bengal Human Rights Commission, and as the chairperson of what is now known as the Indian Institute of Cerebral Palsy.

So much of her story has been recorded, with extraordinary sensitivity, by oral historian Aanchal Malhotra in the book, Remnants of a Separation. But in listening to Uma Ahmad speak, I was most interested in understanding her idea of home — not least because she had witnessed a subcontinent, and people’s homes, being pulled asunder, but also because she had called so many places home in the course of her life. Was home Jalandhar, Lahore or Kolkata? Were they all home? Was England ever home?

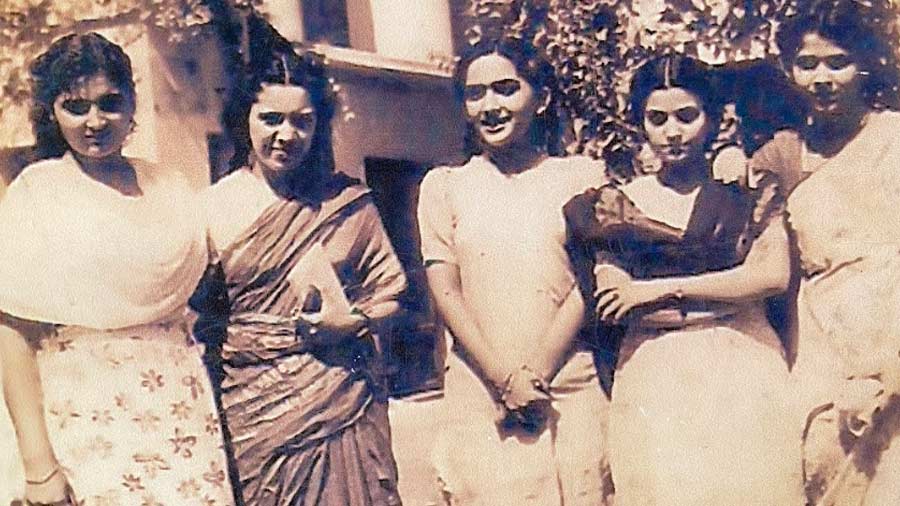

Uma (second from right) with her college mates in Loreto College

She did try to answer my question, but it was evident that one inextricable thread — Mumtaz Ahmad — ran through the seams of her notion of home. “They met when she was a young, working woman with a gang of friends in Calcutta, and he was a young executive,” offered Anjum Katyal. “I remember an aunt telling me that they would quarrel like siblings, but even as children, we could tell that they were extremely bonded.” Her mother smiles, obviously remembering something. “Our union was not without opposition,” she said. “But Mumtaz never let me feel any of it.” As mother and daughter recount the life they lived as a family in Calcutta – a life of privilege, but never one of excess – it is the story of a life that rings familiar. It is a pleasure listening to the two women talk about Mumtaz, especially Uma: “I was a little hesitant initially, but we had a very strong connection.”

It was just as much of a pleasure observing her reminisce about her time at Loreto, especially as a teacher. Does she have memories of Sister Cyril? “Of course!” Her face lights up. “We did a lot of work together. She was fond of Mumtaz, and became close to the family. She had a terrific sense of humour, visited the house a few times, and loved her puri aloo.”

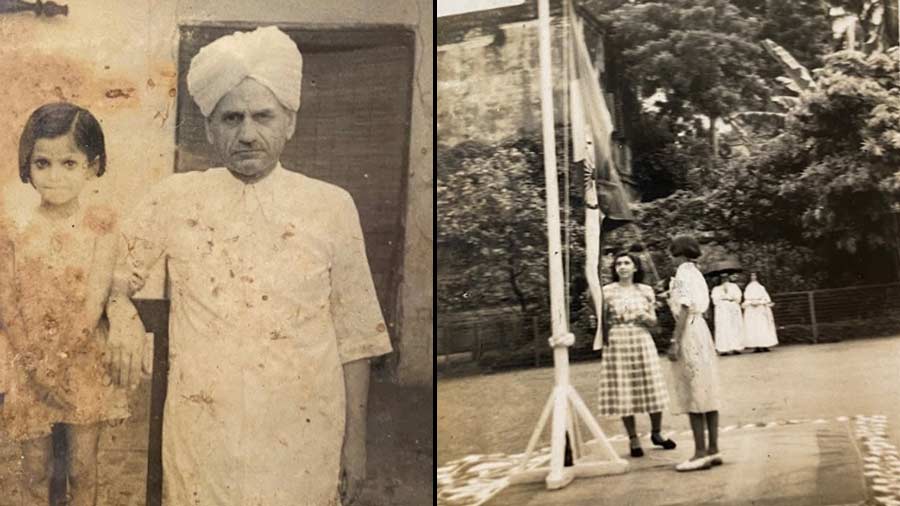

Uma with her grandfather, Lala Shiv Lal Sondhi (circa 1936), and (right) The Indian flag being hoisted for the first time on the Loreto House premises

‘Our minds and hearts remember what they want to’

But if there is something that stays with me the most as I listen to Uma Ahmad’s voice, it is her vivid recollection of the actual spaces she inhabited, rather than the political realities they were embroiled in at the time. In Lahore, she remembers the Mayo Gardens, White House Lane’s trees, and the famous Anarkali Market at the centre of the city. In England, she remembers the church with a flower-lined compound that was visible from their third-floor window (“It was so beautiful, with the flowers growing, that it has remained in my memory”); and, of course, she remembers Jalandhar. I ask her why these images, in particular, remain entrenched in her memory; “I can’t explain it myself,” she says, almost absent-mindedly. “I suppose our minds and hearts remember what they want to.”

Uma and Mumtaz Ahmad at their wedding reception

What is home, then? Does it endure, even if left behind? “Jalandhar was home, you know,” she says, suddenly wistful. “We spoke in Punjabi, my grandparents spoke in Punjabi…” And Lahore? “I loved Lahore, but it was different,” she said quietly. “It wasn’t home… I went back to Lahore after I got married, and I thought I would feel sentimental when I saw my little balcony and the compound I used to walk in. But I did not.”

Uma and Mumtaz Ahmad with their daughter, Anjum (Katyal)

In this complicated map of home, where does Calcutta – her city of residence for so many decades – find itself? “I will be here for the rest of my days,” she smiles, looking directly at me. “Jalandhar and Lahore are a part of my past; they will never come back, and I cannot go back. But they are not forgotten; similarly, I cannot forget Calcutta, its atmosphere, and its people. Mumtaz and I built a life here; this city is a very accepting place.”