Most great endeavours start with a promise and culminate with a purpose. Shantanu Moitra’s Anantha Yatra, which involved him cycling from Gomukh to Gangasagar in less than two months, was no exception.

When Moitra began in early October, he set out on his odyssey with a promise to “attain closure through adventure sport”, to push himself to cover more than 3,000 kilometres in what was to be his most gruelling expedition till date. (The music man-cum-intrepid traveller had earlier completed 100 days in the Himalayas.) By the time Moitra wrapped up his trip, he had not only identified, but also fulfilled, his purpose – to pay tribute to those who left us too soon as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Over the last few weeks, My Kolkata has documented the last leg of Moitra’s Anantha Yatra in West Bengal besides unravelling the heartwarming invention that has secured the legacy of Moitra’s mission. Now, it is time to look at the inside story of the Anantha Yatra through the eyes of those who made it possible.

“Death makes us all one. Rich or poor, good or bad, it unites everyone. Covid-19 made me realise this truth about death more pertinently than ever before,” recalled Moitra, moments before planting photographs infused with Tulsi seeds at Shridham Gangasagar Swami Kapilananda Vidyabhaban as a homage to the victims of Covid-19.

After losing his father to the virus in May, Moitra wanted to realise something he had planned for a long time, four years to be precise. He wanted to cycle from the source of the Ganga river to the point where it merges into the Bay of Bengal. “I just felt that tracing the Ganga would give me a lot of insight into our great country, and by extension, into life,” explained Moitra.

We can come together emotionally and spiritually: Shantanu

“The isolation I saw during Covid, everything else pales in comparison to that. For 15 days, my father, otherwise an extremely social man, could not speak to anybody. I doubt he could even figure out which doctors were treating him. That sense of isolation makes people helpless. I wanted to do something to counter that helplessness, to show people that even in times of grief, we can come together emotionally and spiritually,” continued Moitra.

The first person to know of Moitra’s idea for the cycling tour was Abhra Bhattacharya, a documentary filmmaker and producer who has worked with the likes of BBC and Channel 4. “Shantanuda met me at a wrap-up party for one of my films and in his characteristic manner surprised me from behind! That is when we first discussed the idea,” said Bhattacharya, who is the executive producer for Songs of the River, the tentative title for the documentary that will capture Moitra’s remarkable journey and is currently in post-production.

Shantanu with his team for 'Songs of the River' Parashar Baruah

Once Moitra’s necessary training was complete, which involved building sufficient mental and physical endurance besides cultivating a deep bond with his cycle, he came up with the precise route for his Anantha Yatra.

Beginning at Gangotri in Gomukh, Moitra would chart his way through Harsil, Rishikesh, Kannauj, Varanasi, Patna and Bhagalpur before entering his home state of Bengal and cycling through Murshidabad, Chandannagar and Kolkata to eventually reach Gangasagar.

When the Anantha Yatra halted briefly to take in the beauty of Rani ka talab in Fatehpur Parashar Baruah

That is why I fell in love with him all those years ago: Sarada

“He has always been an enigmatic character with boundless energy. That is what made him pull this off and that is also why I fell in love with him all those years ago,” confessed Sarada Moitra, Shantanu’s better half and the one who always ensured that every member of Moitra’s team was at ease throughout the gruelling journey.

Wasn’t she scared when her husband decided to undertake this trip? “I wasn’t scared because I know he loves travelling and pushing himself. In any case, I knew I had to be calm throughout, and be there to resolve any crisis. Also, my role was to take care of the so-called mundane things, even something as simple as checking that his phone was adequately charged, because there was no way he would have had the energy left to look after these things,” said Sarada.

“But I also enjoyed being a part of this experience. There were so many places we covered that I wish we could go back to, especially Farakka,” added Sarada, who could often be seen distributing snacks to team members. (I got to sample some sumptuous laddus as a result!)

“She’s the life of the team, she’s also the one who’s best placed to make a behind-the-scenes documentary of our documentary!” exclaimed Parashar Baruah, the director for Songs of the River.

A man’s belief in the river and in himself: Baruah

Baruah outlined the vision for the documentary while waiting for the ferry to Gangasagar: “Every rotation of the cycle’s spokes is a story. We could have simply shot Dada (Moitra) cycling and that would have given us enough matter for a full-fledged feature film. But there are so many incredible people we met along the way, so many incredible things we felt. Each member of our team has been on a personal journey for the last two months. That is what makes this so special.”

Music was never far away from Moitra during his journey as he kept collaborating with artists en route to Gangasagar, including his good friend Mohit Chauhan Parashar Baruah

While Baruah acknowledged that the structure for the film – whether it will be a six-part web series or a feature – is still up in the air, he had no hesitation in defining the primary theme of the documentary: “It is about a man’s belief in the river and in himself. Most importantly, it is about how the river and humanity are bound to each other, each reflecting the other.”

Moitra would agree with Baruah’s characterisation, for he himself observed how, after finishing his journey, he had a deep sense of satisfaction at “feeling one with the water. I felt that just like the river merges into the sea, my ego, too, had melted away and become part of some larger consciousness that had coursed through the river.”

Shantanu at the Gangasagar beach moments after completing his expedition Parashar Baruah

This “larger consciousness” was something Moitra’s entire team could feel a part of when he finally overcame an accident, a bee sting, and a race against the sun to reach the Gangasagar beach. “When I’m cycling, I’m in the zone. I’m painting pictures in my head, coming up with tunes, and taking in everything around me. But those last few hours when my right shoulder was not moving (as a result of colliding with a stray cyclist en route) and my eyes had been stung, I acquired a sort of tunnel vision. I just wanted to reach the finish line,” said Moitra.

Overwhelmed to see Dada cycle the way he has: TAPS

Among the most jubilant in Moitra’s team in Gangasagar was Tapan Yadav, the “all-rounder” whose mandate included everything from readying the cameras to arranging for food to cracking one-liners that left everyone in splits.

“I have just been overwhelmed to see Dada cycle the way he has. The passion and the strength he has shown is beyond belief. Nowhere was this more evident than in the mountains of Uttarakhand where the thin air made it difficult to breathe, let alone keep cycling for hundreds of kilometres,” said TAPS, a nickname bestowed on him by Gordon Ramsay during the celebrity chef’s trip to India a few years ago.

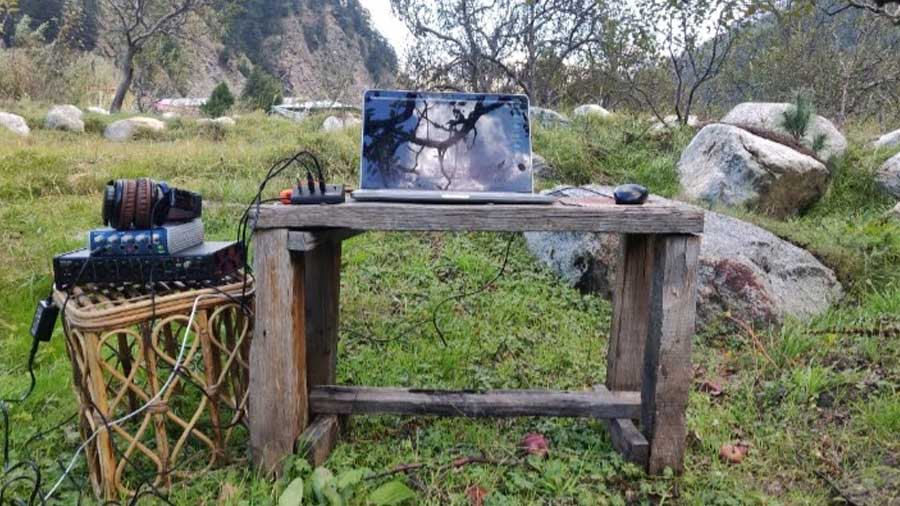

Dholakia improvised to make a recording studio out of a picturesque orchard in Harsil Yogi Dholakia

In agreement with TAPS, Yogi Dholakia, the sound engineer for the documentary, also picked the mountainous terrain near the Himalayas as the most challenging part of the journey: “As always with Shantanu, challenges get the best out of him, and on those tricky roads in the hills, he probably cycled his best. The stamina and the resolve he has shown throughout the expedition has left a deep impression on us all.”

The impression left by Moitra’s accomplishment will soon extend to countless more once Songs of the River is released. But for those who lived the Anantha Yatra in person, the memories, just like the Ganga, are unlikely to ever stop flowing.