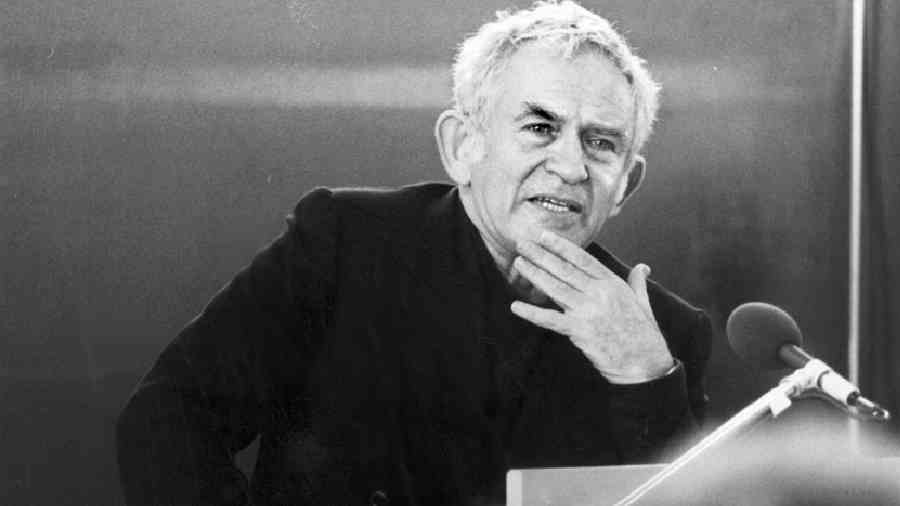

With the bluest of eyes he transfixed me with their electric attraction. At 75, the baddest boy of new journalism Norman Mailer spoke with me about his volcanic life and writings in Bangkok’s historic Author’s Lounge at the Oriental Hotel 24 years ago. He was a distinguished guest speaker at the glittering 20th Anniversary South East Asian Writers award’s ceremony. Now seems to be an appropriate time to pay a tribute to the American writer who would be 100 years old in a few months, had he been alive.

Norman Mailer was the ultimate provocateur of the literary arena of the 20th century. Mailer was born in New Jersey, the only son to well-to-do Jewish parents, with a mother who gave him unconditional love and a humongous appetite for ambition and a father who was a gambler and familiarised Mailer with the thrill of risk-taking. He grew up in Brooklyn and began attending Harvard University in 1939 studying aeronautical engineering. He was just 18 when he wrote his first story. His debut novel, at the age of 25, was The Naked and the Dead. He died at the age of 84, and was the recipient of two Pulitzer Prizes — one for The Armies of the Night, for the 1968 account of a peace march on the Pentagon; and the other for The Executioner’s Song, about the life and death of a criminal, Gary Gilmore, in 1979. The Armies of the Night is often critiqued as “a funeral ode for an idea of writing as civic participation as it is a beacon of a new journalism to come”.

Launching an effervescent literary career in 1948 with The Naked and the Dead, Mailer is still considered one of America’s finest literary geniuses. Other highlights of a long, distinguished and controversial career include The White Negro, Advertisements For Myself, Why Are We in Vietnam, The Executioner’s Song, An American Dream and, of course, The Taming of Denise Gondelman, the artful tale of sleeping with a 19-year-old Jewish girl from New York, where the description of a blow job made the Mailer name universally synonymous with a writer who consistently shocked the public out of middle-class morality.

Few celebrated and exceptional writers can claim to have stabbed their spouse with the kind of passion and impunity that he did, puncturing the cardiac sac of Adele, one of his six wives, as if it was the most natural thing to do during a lovers’ fight. His unconventionality as a writer matched his wild life. Little wonder then that in one of the most talked-about judgements the judge on this notorious attempt at murder declared that Mailer was unable to distinguish fact from fiction. The magistrate declared: “Your recent history indicates that you cannot distinguish fact from reality.” For this outrageous act Mailer was committed to Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital. So, despite the magic of Mailer and his genius and formidable body of work, did this abnormal act cost him the Nobel? Perhaps. The jury’s still out on that one.

The feisty and out-of-control genius was a kind of frontrunner of what was termed ‘New Journalism’, where life writing, news, political and social commentary were creatively knitted together to become a new kind of fiction. But he paid a price.

Norman Mailer (third from left) at an anti-war demonstration

Of all the concision and clarity (and honesty, I might add) in our conversation, what I recall with great delight was my asking him very hesitantly about writing himself into his novel by referring to the incident with his wife Adele, and his response. “Yes, it was an intrusion. I wrote a page or two about my marriage with Adele. It is no secret that my marriage ended after I made an assault upon her with a penknife. I felt I had to include this incident. By leaving out this incident, I might be writing a false book. However, I believe writing is a far more important thing I have done than the public life I have had. I’m going to be there for my work, not my presence on the public scene. For me, fiction and history are very much alike,” he said honestly and categorically.

Now, years later, as I mull over the blurring borders Mailer spoke about in our interview, so many years ago, I do believe that was the problem, or the magic, of Norman Mailer. A contemporary star of Mailer’s time, the great historian Hayden White made a career out of theorising this dilemma about history being fiction, and fiction history.

As bar brawler and drinker (with a penchant for drugs), arm-wrestling specialist, film-maker, actor, and would-be politician, Mailer first announced his candidacy as Democratic nominee for the mayoralty of New York in 1960, advocating that the city secede from the state. The campaign was abandoned soon after the pre-campaign party at which Mailer was arrested for stabbing his wife Adele with a knife.

Bangkok, at once unconventional and royal, patriarchal and perpetually in awe of feminine beguilement, got a fitting dose of sparkle with Mailer’s visits. And it was fitting, too, that the sparks flew from a living literary legend celebrating the diamond jubilee year of a spectacular life. When we met, Mailer’s left knee was severely arthritic and he carried two canes with spectacularly carved silver headed cougar tops, to help him walk. Dapper and soft-spoken, somewhere in my head I was trying to figure out how this man with his distinguished head of thick, short, white hair, brushed back in the ’60s Hollywood style might have actually tried to murder his spouse with a pen knife. Intelligent and confident women seemed to fall completely in lust of him despite his chauvinist proclamations against feminism.

What the 300-odd strong audience in The Oriental Hotel’s packed ballroom got was a fiery dessert — a quintessential Norman Mailer— charming, spirited and dazzling. The evening was a charmed one with HRH Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn presiding and the haute monde of Bangkok dressed to the nines. “That was a very good audience. I was wondering whether to give that speech or not because most audiences would be bored by such a speech. But this audience was so impressive,” he said, after the SeaWrite award presentation, during which the Pulitzer prize winner spoke on the perils and gifts of writing.

What role does the editor have in making a great writer, I asked. Referring to his editor, Jason Epstein, who was travelling with him on this trip. Mailer replied: “He’s a very good editor but a very difficult man. He’s terribly opinionated. It’s not easy to write. You have to give as many years to get ready to write as a pianist must practice to express the music of his soul,” explained Mailer, who cited Ernest Hemingway and D.H. Lawrence as his personal literary heroes.

His close friend and editor of 45 years, Jason Epstein described Mailer with affection: “I’ve known him for a very long time. Norman’s a difficult man. He was always making trouble. He was very stubborn and he would never take advice. Never. And he still doesn’t.

“He did the silliest things and had to be pulled out of trouble constantly. He makes Clinton look like a choir boy. But he’s a wonderful man. Brilliant.”

Epstein, editorial director of Random House for several decades and vice president, published this century’s greatest authors — Nabokov, Philip Roth, W.H. Auden, Edmund Wilson, Gore Vidal. Mailer, he stresses, was a gentleman in his dealings with the publishing world, unlike many authors he describes as opportunists. “Norman began with a bang in 1948. He wrote the first novel, The Naked and the Dead to huge critical and commercial success. He became very famous. And he remained very loyal to his first publisher. It wasn’t until his first publisher died that I began to publish him, about 15 years ago.”

What was it that impressed Epstein most about Mailer? “The energy, the intelligence, the seriousness. He took everything seriously. Everything mattered to him. He had to understand what was happening all the time. He has a brilliant mind. Some of his best work is his political commentary.”

“Underneath it all, he is a very sweet Jewish boy. He has good genes, and still looks good. He’s very playful with his children. If he hadn’t respected marriage and family, he wouldn’t have got married so often. He didn’t believe in contraception. He believed in having babies. And now he has to pay for it. They were expensive,” said Epstein with a laugh.

A bad cook, according to his friend Epstein, Mailer learnt his culinary skills in the army. Mailer, who hung out with a lot of different kinds of people in the ’60s — some of his favourites being prize fighters, and jazz musicians and writers — is wary of befriending other writers. Epstein explains: “Authors at the top are very competitive, really, and they don’t have much to say to each other. “Their books are in their heads and they can’t discuss their work. If he spent his time with other writers, he wouldn’t do any work at all.”

Genuine in his praise of Bangkok, Mailer added: “I would like to come back here. Bangkok is a feast for the eyes. Living in America, your eyes go dim after a while. There is nothing new to look at. Every city looks like every other city. I am looking greatly forward to Vietnam, too. You see, the war meant so much to me. I am so opposed to the Vietnam War. I’m just so curious to go there.”

Mailer, in his Southeast Asian Write (SEAWrite) address, won many fans with his vibrant and witty speech, his voice sincere as he commented on how much he was charmed by the wonders of Bangkok, and that he was keen to come back to Asia. He was drinking only the occasional glass of wine, leading what would be termed a quiet and charmed life with his sixth wife Norris, and avoiding the temptations of big city bright lights. Married for the sixth time, to stunning Norris Church, who accompanied him on the trip to Asia, Mailer was, perhaps surprisingly, quite a devoted father. He met his nine children by the various wives often, throughout his life, when he was not writing furiously from his seaside haven in picturesque Cape Cod.

Mailer seemed to me to have come a long way from the wild years of a long and indomitable youth. But the fire was still burning, and under those clear blue eyes was a vision that would make him write more real stories that were stranger than fiction. One hundred years on, and he is still considered the original phenomenon in 20th century publishing.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance of Life and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Kolkata and teaches Masters English at Loreto College