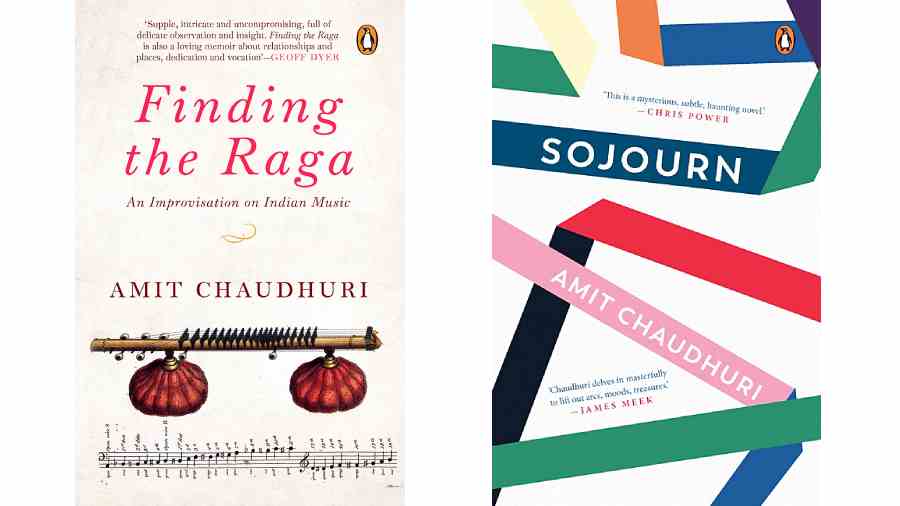

There are very few who can pursue two things at the same time, with the same passion and commitment. Author Amit Chaudhuri is one of them. While he became eight novels old with Sojourn, which was released last year, his musical trajectory is also moving in a new direction as he dropped a new single, In A Silent Way/Indian National Anthem, early this month. The track commemorates the 75th anniversary of India’s Independence and has an ‘East meets West’ flavour with the composition of Australian keyboardist Joe Zawinuland Rabindranath Tagore melding organically like one entity. We caught up with the novelist and trainedHindustani Classical music artiste,who recently won the James TaitBlack Memorial Prize for his book Finding The Raga: An Improvisationon Indian Music, and spoke at length about his process of bridging the gap between raag and blues, why Tagorewas the most remarkable songwriter and why he feels watching OTT is hard work.

The national anthem for the population at large is a nationalist entity, when did the anthem acquire a different meaning to you?

I cannot pinpoint exactly when but I must have begun to think of it as a musical composition and not just the national anthem early in my life. I think the first time it happened was in 1980 after India won gold at the Olympics (in hockey). It was a rare occasion and the way the band played made me realise it’s a very beautiful piece of music. I think it was played without too much emphasis or too much speed; there was a kind of mellowness about it I realised how lucky we are to have an anthem which sounds so beautiful. And that’s not really surprising because when you think about it Tagore was a great and innovative songwriter, probably the most remarkable songwriter of the 20th century. In response to this particular recording, Wendy Doniger, the historian, said to me that, this is her favourite anthem. I think it’s mine too. There are very few anthems which sound expressive in that way.

And when did Joe Zawinul and his composition come into the picture?

It was just accidental. I was listening to In a Silent Way by Miles Davis; the composition is Joe Zawinul’s and the notes of the national anthem came to me and I began to sing it as one would sing a composition. There are things about the composition which are peculiarly Tagorean. Tagore often slipped in certain notes from the raga Kedar into his songs – I mean tivra ma pa dha ma. It seems to be a phrase that haunted him. He brings it in here, the word Maratha in the lines… Punjab Sindh Gujarat Maratha. And for me, it’s a very moving phrase, and I’m interested in how Tagore also finds it moving and brings it into his songs repeatedly. So, there were various things that were going on in my head when I was rethinking this song.

So you started to view the national anthem differently in the 80s and the track has been released now in 2023. What happened in between and why did it take so long?

Yeah, so at that time I used to play Western music with a guitar and I had been learning Hindustani classical music for two or three years; I was learning the khayal. By the time I went to England in 1983, I only listened to and practised and sang Hindustani classical music. I had stopped playing the guitar and I stopped listening to Western pop music until I came back in 1999. So 16 years as a student, and then you know, as a published writer I did not listen to Western contemporary music. And then in 1999, or around the end of the 90s, I began to listen to my old records again. And it was at that time that I began to listen to Jimi Hendrix playing the blues and I began to hum certain pentatonic raags like Jog, Dhani and Malkosh, because the blues is a pentatonic scale. It was the way he was playing the blues that reminded me that there are common roots to the raag and the blues. Again while I was practising raag Todi, some of the notes I was singing reminded me of the riff to a song called Layla by Eric Clapton. So I thought, should I explore this in terms of composition and improvisation so that I can improvise in a way that I would move from Todi to Layla and Layla to Todi; from raag to the blues, and back. At first, it seemed like a strange idea but I followed through and that’s how the project began.

So, it’s a particular kind of journey; things happen when they happen; I wait for them to happen. They happen organically and I try to be true to what happens. And then, of course, the pandemic held things up — otherwise, I maybe would have recorded the album three years earlier, four years earlier. People who played with me moved elsewhere plus the music scene has changed.

What kind of change are you referring to? Can you elaborate, please?

There is very little space for new music anymore or encouragement for new thoughts to do with music in Calcutta and in India. So anybody who wants to be a composer has to go to Mumbai and try their luck in Bollywood. Why is there no independent compositional space for new music? This is a space that was created by people like Tagore and various others in different parts of India, why is there no space now?

Don’t you think the independent music scene in India is on a high now?

These kinds of music have predefined characteristics. But there must be a space to create a new vocabulary. Also, there should be listeners and supporters of the new kind of music. When I started this project, I would say there were more people who were interested in new things but it has dried up and it has dried up all over the world. Many independent venues shut down in the UK after the 2008 crash.

The Hindustani classical scene is also not a place for experimentation although Hindustani classical music emerged as a form of experiment through centuries. The 20th century is a time of great experimentation and khayal itself is a result of the experiment; its development is a form of experiment, a huge radical experiment. But the Hindustani classical music space is now a space for shastriya sangeet — music that’s treated, often superficially, as sacred heritage rather than a form of ongoing thinking.

Let’s get back to the album. Take us through the track.

There’s Adam Moore on guitar, Matt Hodges on piano and then you have the bass guitarist Paul Williams. The tabla player, Nafees Irfan, was unwell that day. He’s played on three of the five tracks on the forthcoming album. They’re all wonderful musicians and human beings. Adam has done a great job of mixing this song. The nice thing about In A Silent Way is that it is ostensibly simple; it is also in free time and that makes it a bit like a tanpura. Whether it was Mile Davis, John Coltrane, Zawinul, The Beatles or Jimi Hendrix, they were all listening to Indian classical music at the time and its expansiveness is there in In A Silent Way as well.

Where was it recorded?

At St. Martin’s Church in Norwich that has been converted into a studio called Fine City Recording Studio.

When are we going to see you perform it live?

I have performed it live in Calcutta but a long time ago. I have performed it in London and it’s there in a film called him Moment of Mishearing. I would like to perform it and some of the songs from this album, maybe once it comes out.

When is the entire album coming out?

I hope in February.

Moving on, you straddle two worlds — one is music and the other is writing — and both are equally strong. Which one do you enjoy more or are more passionate about?

I am passionate about the act of creativity. And it takes up all my time, partly because one has to justify doing it. It’s not an easy thing to do, firstly, in terms of the time it demands from you, and secondly, to justify the act of creation. Also, it involves a sense of trust which is not easy to sustain over decades — you’re trusting that someone out there will respect and respond to the fact that you’re undertaking the creative work on your own terms, not theirs.

Talking about these two different sides to you, these two talents, do they support or aid each other any time in the process of creativity?

Each comes with its own set of possibilities and excitements and problems. So I’m fortunate that I can respond to these various kinds of possibilities. I think more and more of me is involved in things that I do, whether it’s critical writing, fiction or music. There is no direct correlation.

What’s next after Sojourn?

I have the idea of a novel in mind but I am also working on several essays at the moment.

What are you reading at the moment?

I kind of move from one thing to another and often reread things. I am reading three or four novels at the same time, all by European writers. And I’m rereading Virginia Woolf’s extraordinary A Room of One’s Own.

And what are you watching?

I watch to unwind. Sometimes it’s hard work; so much of the stuff on platforms like Netflix is so joyless that it feels like punishment. Right from an early age, I have been into murder mysteries and crime thrillers, which at its minimum can divert you and at its best, it can be wonderful, as with Hitchcock.

Pictures by B. Halder