24th August, 1690 - The iconic date when Job Charnock’s party landed at a ghat in Sutanutee, heralding the growth of British settlement around these parts, a date that has been celebrated often as Calcutta’s unofficial birthday, the Calcutta High Court order prohibition notwithstanding. But sifting through the pages of history we arrive at another date, and a personality – both forgotten – whose contribution to flourishing and permanency of the English settlement was unarguably more profound than Charnock’s. Today, I narrate his tale.

Charnock’s final return to Calcutta did not last long, he passed away in 1692. The early years of the East India Company settlement in the area were one of struggle. Mughal badshah Aurangzeb and his dewan in Bengal, Murshid Quli Khan, both had little love for the foreign arrivals. Earlier bitter experiences with the Portuguese had left the Mughals jittery. In lieu of allowing the English East India Company to trade, the rulers of the land continued to extract a hefty pound of flesh in the form of tributary payments.

Aurangzeb’s death in 1707 plunged the country into uncertainty as a bloody civil war broke out in Delhi. Eventually, Shah Alam I ascended the Delhi throne and the Company promptly sent a payment of forty-five thousand rupees to continue to enjoy the trade privileges bestowed upon earlier. But even as Delhi throne was placated, trouble was brewing locally.

Murshid Quli Jafar Khan

Murshid Quli Khan, taking advantage of slew of weak rulers in Delhi, had consolidated his powers. His old animosity for the English also remained strong. Troubled by his continued exertions, in 1715, it was determined that a plea needed to be sent to a higher authority – being badshah Farrukhsiyar in Delhi. The 10th Mughal sovereign had earlier intervened to issue an order instructing his dewan to stop interferences in matters of the Company. So it was with much hope and optimism that a messenger party set out on for Delhi in April of 1715. Leading the contingent were John Surman and Edward Stephenson – widely acknowledged as two of the best men in the Company’s service in Calcutta.

Khoja Serhaud, a rich Armenian merchant, went with them as the official interpreter. William Hamilton, a Scottish surgeon on the rolls of Fort William, rounded off the party. To appease the emperor, they carried present estimated to be worth thirty thousand rupees.

On the 8th of July, after a three-month journey, the Company representatives arrived at the Mughal capital. But the optimism with which they set out soon started to evaporate. Months passed but an audience with the emperor remained elusive. It would be January, 1716, before the Company envoys were able to place their petition with the emperor. What followed was another round of waiting which was interrupted by a happy piece of serendipity.

News came in that Farrukhsiyar was suffering from terrible pain due to a swelling in his groin area that had rendered him near invalid and worse, had delayed the emperor’s daughter’s marriage functions. Hamilton was called in take a look at the ailing ruler. His treatment worked and for some time, Farrukhsiyar got better. A few months later, the pain returned. Once again, Hamilton was called in and once again, he was able to restore the emperor to good health. Most importantly, Farrukhsiyar was finally able to perform the wedding of his beloved daughter with the daughter of the Rajah of Jodhpur.

An overjoyed emperor held Hamilton in much gratitude and presented the Scotsman with a robe of honour, an elephant, a horse, two diamond rings and five thousand rupees. But not deeming these sufficient, Farrukhsiyar asked Hamilton to name any reward “he wished for”. The good surgeon, however, proved to be an extremely unselfish man. He immediately asked the emperor to grant the Company mission the objective with which they had arrived from distant Calcutta.

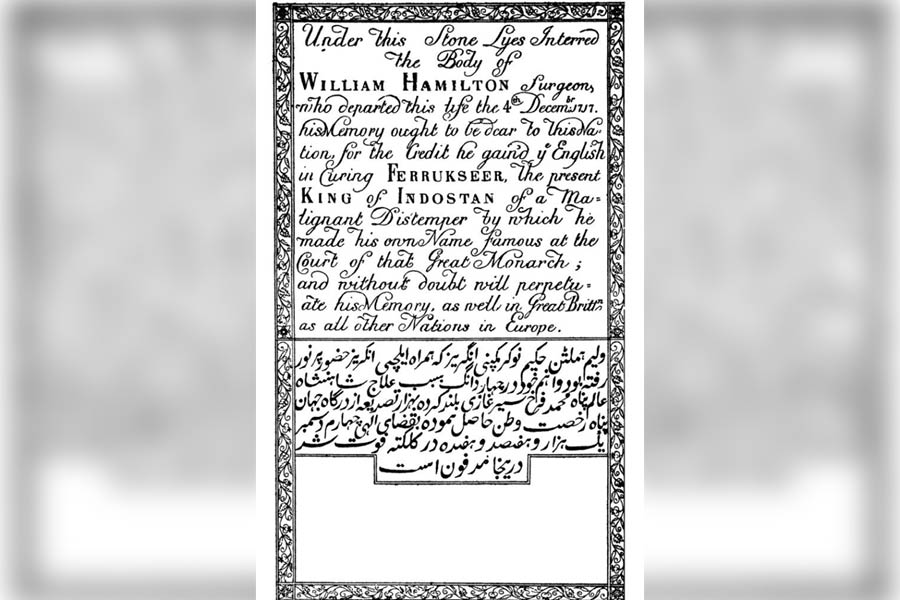

The engraving on the headstone of Dr William Hamilton’s grave at St John’s Church compound, next to Charnock’s mausoleum, in Kolkata’s Dalhousie area

After another round of waiting, eventually, in the April of 1717, a royal firman* was issued to Surman, granting the (East India) Company the privilege of free trade (without payment of taxes) and also permission to purchase 37 villages adjacent to the original three (Calcutta, Sutanutee and Gobindapur) acquired in 1698. Additionally, the Company was allowed to extend their domain of operation 10 miles south of Calcutta along the bank on either side of the river Hooghly.

Despite the interminable wait they had to endure, Surman and Stephenson’s mission was an unqualified success and returned after more than two years to rapturous welcome to Calcutta in November, 1717. Sadly, Hamilton, who possibly deserves most credit for the success did not live to savour the moment. He died on December 4, 1717, and is buried at St John’s Church compound, next to Charnock’s mausoleum, in Calcutta.

Murshid Quli Khan, the old bête noire of the Company, had in 1717 broken free of Mughal rule and declared himself independent nawab of Bengal, shifting his capital from Dacca to Murshidabad. His bitter resistance meant the Company was unable to acquire the 37 villages granted in Farrukhsiyar’s firman. However, the right of duty-free trade and other privileges that were delivered by the royal order went a long way in firmly entrenching the Company’s stronghold in Calcutta. With safety more assured than ever before, the fledgling metropolis was soon flooded by private merchants and fortune seekers – not just British but also Portuguese, Armenian, Jewish and Indians as well. The activities at the Calcutta port grew manifold as did the Company’s business. It was truly acchhe din and the future was never brighter.

*firman – royal order

Acknowledgements: Calcutta – Old and New: A Historical & Descriptive Handbook to the City, H.E.A Cotton (W. Newman & Co.)