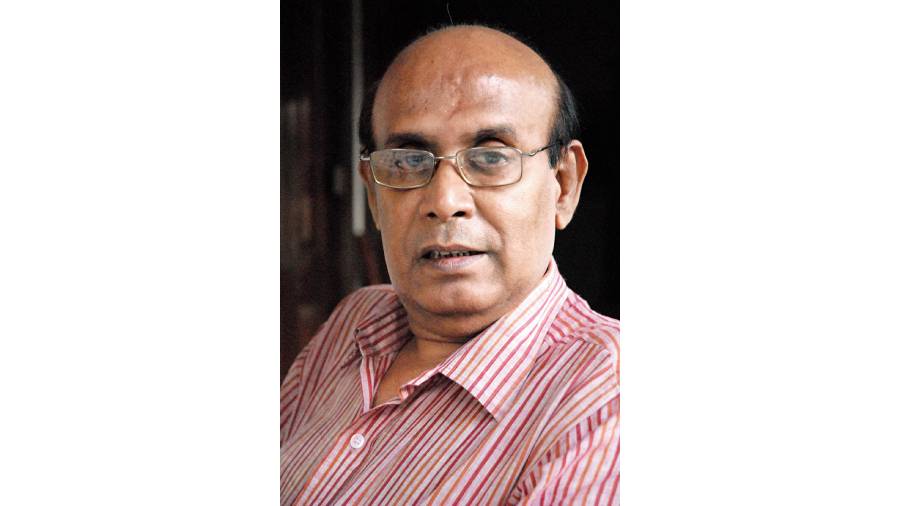

Eminent filmmaker and poet Buddhadeb Dasgupta, who had been battling kidney ailments for quite some time, died at his home in Calcutta early on Thursday, family members said. He was 77.

After watching my Bengali version of Peter Weiss’s Marat/Sade on stage, he came backstage to ask whether I would be interested in acting in his film. That was in 1980. The film Grihojudhdho happened much later because of funding crises. By that time Mrinal Sen had contacted me and I had shot for his Chalchitra.

My journey with Buddhadeb Dasgupta, like with most of my directors, have been very personal. In these four decades, I actually worked with him in three projects and dubbed for one. My output with most directors is equally limited. Yet, the connection was not that of just an actor.

We met up frequently to drink some of the best vodka he bought and discussed his films, his poems, my theatre or songs. When I made The Bong Connection, he was my only director who stood in a queue, bought a ticket, watched it and called me up to say that he loved it.

Now, there was a huge difference of opinion regarding cinema between us. I, being essentially populist, never imbibed anything from his works, neither from the makers he admired. Yet, to my mind, Buddhadeb Dasgupta was perhaps one of those very few Indian filmmakers who found a certain self style which was very different from the legacy we have all inherited in the 1980s.

He won awards, sizeable international acclaim, but never found box office at home. This lack, never for once distracted him from his course. Being a highly accomplished Bengali poet, his cinema became an extension of his languid, almost surreal poetry.

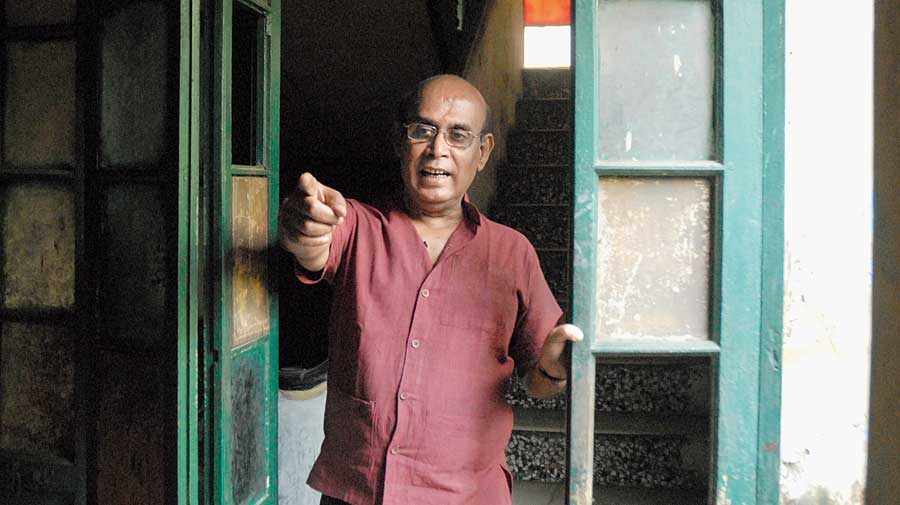

Anjan Dutt is an actor, filmmaker and musician File picture

When I called up one of his highly accomplished contemporaries, Goutam Ghose, this morning, he reiterated this more clearly.

“Buddha’s films are marked by his gradual evolution from realism to the surreal,” he said. “Duratwa, Neem Annapurna, Grihojudhdho… to Tahader Kotha, Uttora, Swapner Din right up to his last Urojahaj… as he kept making films, he moved from the very gritty real to a complete unreal space where he told us fascinating stories which were defined by a certain magic realism so rare in our cinema.”

During his TV project, Sheet Grishmer Smriti, way back in the 1980s, I had great difficulty acting because of his extremely long, complicated trolley shots which had to be done without retakes because of limited celluloid.

I, with whatever limited understanding of method acting, felt like a puppet trying to keep pace with the camera during every rehearsal. Buddhadeb would pamper me before the shot and this rather gawky, almost erratic 27-year-old actor ended up without mistakes.

Born in 1944, Buddhadeb Dasgupta grew up in the 1960s, being influenced by auteur filmmakers of Europe through the film society movement. I had to move away from my favourite British and American method and watch a lot of Hungarian and Russian actors to be assured of what he implied. In the process, Buddhadeb Dasgupta opened up the whole world of East European cinema to me.

After almost 10 years, he cast me as one of my most favourite literary characters, Satyacharan, in his Hindi TV adaptation of Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s Aranyak. I knew fully well that all my preparations would lose out to his focus or attraction for nature itself. It did.

By then, I had grown older and matured enough to hang on to my motivations irrespective of the fact what the camera was doing. The drift is basically that my acting school was the art house directors of the 1980s, Buddhadeb Dasgupta being one of them.

When I called up one of his other highly powerful contemporaries, Aparna Sen, she said: “I love Buddhadeb’s films because of their inherent poetry and visual lyricism.”

Though I have read some of his poems and do like them very much, my songs have very little connection to modern Bengali poetry. Yet, from day one, Buddhadeb was an ardent admirer of my songs and was a regular at my early concerts.

My last, rather long interaction with him was before the release of my last album Unoshaat. He loved it but kept insisting that I put in different sound effects to enhance the poems. “The music itself is not enough.”

I did not do any such thing. Pink Floyd and numerous other bands have exploited that use to the hilt. Yet, looking back today, I feel he did give some serious thought to whatever poetry I had to offer.

So, when I look back today at his work and the crazy interactions we shared for whatever time, I see someone offering us a whole different world of experience.

I see an array of vagabond, marginalised, social outsiders, drifters and their inability to fit into the system. It is in creating these crazy misfits that Buddhadeb Dasgupta scored.

To me, it is this courage to gradually move out of the stereotype middle class and push the boundaries and look at failed people is what is the most significant aspect of Dasgupta.

His lyricism, poetic imagery, whatever real, unreal, surreal shots he took, becomes far less important to me today compared to the people he showed us. To me, that is the most exciting aspect of Dasgupta’s works.

Grihojudhdho, Phera, Bag Bahadur, Anwar Ka Ajab Kissa, Uttora, Charachar, Urojahaj, Ami, Yasin Ar Amar Madhubala… are all films about misunderstood souls. Though I will never want to walk that non-populist path, being steeped in my own legacy of pop culture, I definitely owe much of my immense love for misfits to my early interactions with Buddhadeb.

During the shoot of Phera, I accompanied my wife Chanda Dutt who was acting in the film to the outdoor location. Most of the time myself and actor Sunil Mukherjee were breaking whatever rules concerned, regarding smoking or drinking. We were frequently admonished severely by Dasgupta.

Yet, almost every punishment ended up with Dasgupta and myself chatting away on cinema over his bottle of whiskey. I will always remember him with a certain fondness that goes beyond the realms of a world-class filmmaker or an accomplished poet. I will remember him as a friend who was there to agree to disagree.

Towards mid-2000, I was commissioned to do a travel-cum-chat show for Kolkata TV. I only chose distinguished people I admire and among them was invariably Dasgupta. Two days in Mirik.

He had severe reservations about shooting while drinking. We had to cut several times during the interview to have our respective sips. The chat got so intense and personal that I had to severely edit. The internationally acclaimed Dasgupta became as much an outsider or a misfit as the characters of his movies. A vagabond hidden behind the look of a professor he once was.

Many will miss him as a highly alternative, poetic filmmaker. Many as an artiste or poet who continuously fought the overwhelming mediocrity. I won’t miss him. Given the severe prolonged ailment he was suffering from. Given the fact that he will live forever through all those misfits he created on the screen. Like in his movies. I am certain he walked out of his door in Calcutta and swam into the sea.