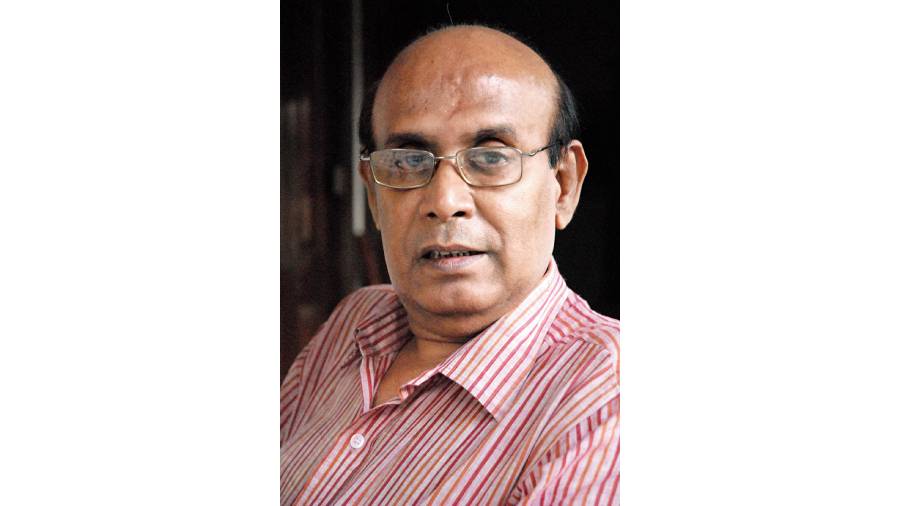

Film-maker Buddhadeb Dasgupta passed away on June 10. Recipient of many international and national awards, Dasgupta’s films were a regular feature on the foreign festival circuit. In his films, characters rooted in reality found strength in memories; they found solace and happiness in the small things in life. The memories provided hope to people otherwise burdened by responsibilities. Childhood memories informed his films too. For example, the origin of Anwar Ka Ajab Kissa lay in his childhood fantasy of becoming a detective.

“In my schooldays I was a big fan of Swapan Kumar. His books were banned in my house but that couldn’t stop me from reading them and dreaming to be a smart detective when I grow up. Anwar is my detective. He is, like most of my other protagonists, a common man, no ambition, no shrewdness but with some innocence and humanity. My heroes are common men who are often failures in other’s eyes. Anwar too is a common man, simple and lousy at times but with basic human goodness,” Dasgupta had told The Telegraph last year.

The process of detection, or discovering something, led his characters on a journey of introspection and exploration.

“Buddhadeb was one of the finest film-makers of our generation. One of his biggest achievements was the way he captured the human condition in a changing world through his films. He had started by making realistic films. Then his cinematic language evolved and took a different turn, with a combination of real, unreal and surreal. Through it all he also depicted socio-economic changes. He used space very interestingly, through a combination of montage and mise-en-scene. He was a poet and he went on to define his cinema in a poetic way. The subject of many of his films were from Bengali literature and those stories, like the stories of Prafulla Ray, found interesting interpretation. Only recently we were talking about the preservation of our films. We were friends for almost 50 years. Some of my fave Buddhadeb films are Bagh Bahadur, Lal Darja and Grihojudhdho,” said veteran film-maker Goutam Ghose, who had acted in Grihojudhdho.

Dasgupta’s film Tope — starring Paoli Dam — was based on a Narayan Gangopadhyay story which he had first read in school. He went back to the story later and decided to make a film, combining magic realism and reality. Folklore played an important element in the film. “This is an end of an era. It was an experience of a lifetime working with him. The way he approached cinema was very unique. One got so much involved in the emotions of the character. Slowly we developed a bonding. And it stayed beyond Tope. I had worked with him in 2008 for a TV series, that was my first experience of working with the stalwart. He had a unique way of telling stories with so many layers, sub-layers, and the subtlety of emotions. He had a signature style with long takes. He shot in natural light and found beauty in a barren landscape,” says Paoli Dam.

Tope Sourced by the correspondent

Urojahaj Sourced by the correspondent

While dreams gave hope, they also overwhelmed someone’s existence. In Urojahaj, a village mechanic dreams of flying. After discovering the crash site of a World War II Japanese plane, he decides to rebuild it... he dreams of flying it one day, and that leads to a series of life-threatening incidents. Ghosts of broken dreams appear too.

“Buddhada was a maestro, one of the finest film-makers in world cinema. I had the opportunity of working with him in two films (Swapner Din and Ami, Yasin Ar Amar Madhubala). It is a blessing for me. I’ll forever remember that experience. I had toured a few international film fests with him and saw how people there would respond to his name, his films, and embrace them. He has given us many classic Bengali films. He was a very kind human being,” said Prosenjit.

Swapner Din Sourced by the correspondent

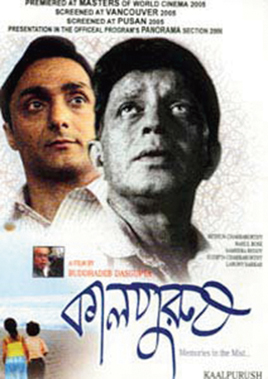

Kalpurush Sourced by the correspondent

“Grihojudhdho and Bagh Bahadur are an indispensable part of my Memory of Cinema. Even his last film Urojahaj bore the stamp of his class and poetry in every frame. Goodbye, Memory-maker,” tweeted Srijit Mukherji.

One of the key themes of Dasgupta’s films was how he framed his scenes. Nature was as much a character in his films and it mercilessly probed the anguish and pain or captured the joys of his characters.

In his films, the vast dusty landscapes, abandoned mansions, the quietness, the rivers and the wind told their stories.

The images vividly captured the breathtaking beauty of a place, evoking feelings of romanticism and melancholy. “I was too much in love with his ability to create pure sketches of art and find a story to fit his vision. He was a true auteur, a poet on and off screen. The last of my heroes whose work inspired me to run to the cinema before cinema was overtaken by movies. I’ll never forget being awestruck by the handheld chaos that he brought to represent a politically distraught Calcutta, the 360-degree undoable shot in Grihojudhdho to the top shots of our city way before the drone was a household transition staple. But it was with Bagh Bahadur, Lal Darja and Uttora at the Lincoln Centre Retrospective that I had fallen in love with this magician in 1996 who showed us the genius of lyricism and a series of frames that could come out of an art history catalogue. I met him briefly over the years many times always tongue tied and in awe and barely could ask him all the questions a fanboy would want to. That opportunity is a lost cause. But is it? Perhaps I didn’t need those answers. His filmography will leave all these questions unanswered and have us asking forever. After all, great cinema speaks for itself,” said film-maker Mainak Bhaumik.

Dasgupta was a warm-hearted, kind and affectionate person. “He had a very unique sense of humour, which was also subtle. He would give actors a free hand. And he would like what we brought to the scene as performers. His eye for detail was fantastic,” said Paoli.

He would talk about the works of the new generation of film-makers and actors. “He was very friendly and sweet to me (during the shoot of Urojahaj), and would always have a word of encouragement every day. I have never seen anybody so passionate. The experience was fabulous, I will always remember it. He did not shoot like everybody else. His style of shooting was very different. He came up with ideas during a shoot. Everything had to be co-ordinated (for sequences). There was massive co-ordination required. The shots were beautiful… a lot of hard work had gone into making them. He was a perfectionist and put in so much effort. I was in awe of him,” said Parno Mittra.

Film-maker Anindya Chatterjee had assisted Dasgupta in his feature film Janala. “To be around such a veteran film-maker during his creation period is itself no less than (sometimes much more than) attending a top-class film school. That experience carves out your artistic journey, and exactly the same had happened to me. Later, whenever I requested him to watch my films (be it my first feature film Jhumura or the short Labourers) he watched those passionately and thoroughly. Never hesitated to criticise or praise with an open heart, or give important opinions. We have lost a world-class artiste. Our generation is not lucky enough to witness (Satyajit) Ray or (Ritwik) Ghatak in their creative time. So we looked up to Buddhada always. Now his demise creates a huge void. I still remember that very important advice that I got from Dada — Paglami ta darkar, bujhechho? (A certain madness is required, understand?),” said Anindya.