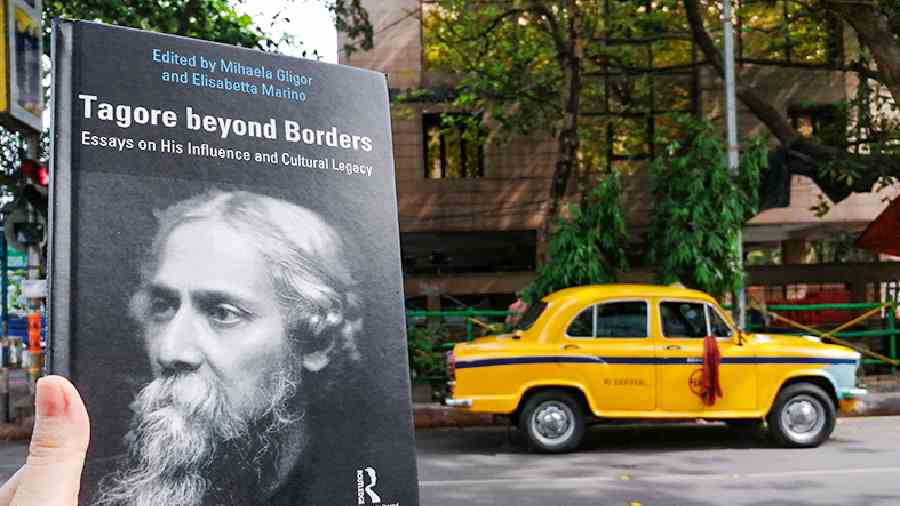

The collection of 11 eclectic essays that constitutes Tagore Beyond Borders will be of interest to readers and researchers in all genres and across disciplines — literature, philosophy, political science, cultural studies, Post-colonialism, religious studies, Asian studies, South Asian studies and Tagore studies. The editors, Gligor and Marino, have collaborated on the project more as a labour of love for Tagore than as their primary areas of specialisation.

Perhaps this is what makes the volume less intimidating for lay readers. However, many of the writers in this volume are experts in their fields of Tagore studies and have mined the archives in Bengali and English. The result is a freewheeling, contemporaneous, enthusiastic exploration of Tagore across boundaries. The fact that Tagore himself has always stood at the smudged boundaries between Universalism and Nationalism, and Cosmopolitanism and Parochialism, makes him a somewhat contested subject for any exploration.

Mihaela Gligor is researcher in Philosophy of Culture at the Romanian Academy “George Baritiu” Institute of History Cluj-Napoca; founder and director of Cluj Center for Indian Studies, Babes-Bolyai University Cluj-Napoca, Romania. Elisabetta Marino is associate professor of English Literature and the head of “Asia and the West”, an international research centre based at the University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy.

Marino has a seminal essay on the letters of Tagore and meetings between W.E.B. Du Bois, the American civil rights activist and one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People and Tagore. Her article invokes Tagore’s call for recognising the universal brotherhood of man by harmonious and equal rights access by all races. Tagore’s cry for love and inclusion of blacks in America is sharply relevant in our times when movements such as Black Lives Matter are making their messages heard every day.

The most powerful and typically rich offering in the volume is Cultural Transfer, Rabindranath Tagore’s Travels and Travel Writing. Gligor was strategic and smart to invite wordsmith and the charming, provocative intellectual Fakrul Alam to this party. The only male scholar to appear in this volume, Alam is probably the most engaging. “Rabindranath was surely prescient if you think of the South-South interactions as well as the North-South ones. By adopting an international perspective and critiquing Nationalism he showed the value of cultural transfer and the importance pf setting up of communicative communities,” says Alam.

“Tagore noted that the dress and ornaments of the Bali women that he met were like Ajanta pictures.” This observation is one of the rare gems that the anthology showcases about Tagore’s influence on and from China and Japan. Alam’s quirky rendition of Where The Mind Is Without Fear, from the Gitanjali, makes for a truly original contribution to this volume.

In Strangeness and the ‘New Woman’: Rereading Rabindranath Tagore’s The Laboratory (1940), Paromita Mukherjee strikes a strong chord and lucidly explores and evinces the idea of the ‘new woman’ in Tagore’s ideation. By unpackaging the story of the Punjabi woman Sohini, married to a Bengali man, Mukherjee brings Bimala into the conversation from Ghare Baire and shows the reader how Tagore persuasively argues the case for gender equality which was taking Bengal by storm in the 1930s and 40s.

In Tagore and Gandhi: Their Deep Thoughts about Their Country, the internationally acclaimed Tagore scholar, perhaps the most renowned repository of Tagore Studies, Uma Das Gupta, focusing on letters between Tagore and Gandhi between 1912 and 1940, points out that their principal goal was India’s freedom: “Their deepest thoughts evolved as they defined their goal.” Das Gupta also presents both Gandhi and Tagore’s letters with C.F. Andrews — all of whom worked for India’s freedom and challenged the empire’s racism that the latter had legitimised. “The difference was that their letters dealt with the political problem not as an allout fight with their opponents but as a conflict of spirit with spirit.”

In an otherwise felicitous volume, some hollows appear. Scholars regard the Index as a map / intellectual road map to the entire book because it provides vital information about people, places, sources and major events. The fact that this book’s index is only three pages long will make it difficult for readers to find what they are looking for in the book. The Index lacks any entry on China and its complete absence in this volume is problematic since the title of the volume claims that this is a book about Tagore beyond borders, and we know how deeply China featured in Tagore’s ideations.

For Japan, too, there are just two entries on pages 14 and 87 in the Index. Considering Japan played a crucial role in the concept of Santiniketan, this is a lacuna that might disappoint.

Readers might find it difficult to navigate through the book because of the lack of abstracts. To locate Tagore Beyond Borders, readers will recall the muchcelebrated compendium of essays Rabindranath Tagore: Reclaiming a Cultural Icon, edited by internationally renowned Tagore scholars and academicians professor Joseph O’Connell and Kathleen O’Connell, and published by Visvabharati (2008).

It is to conceptualiser Mihaela Gligor’s credit that she has bestowed a new testimony to the abiding legacy of one of the greatest writers and philosophers of all time 15 years after the last compendium was published. Arguably a difficult task, and enormously challenging in scope and reach, Gligor’s attempts to give us a bird’s-eye-view of the Nobel laureate’s indomitable presence 80 years after his death is to be commended.