With 60 translations and counting, Sinha has won the Crossword Award twice, including for Sankar’s iconic Kolkata novel ‘Chowringhee’. My Kolkata caught up with him between the written word.

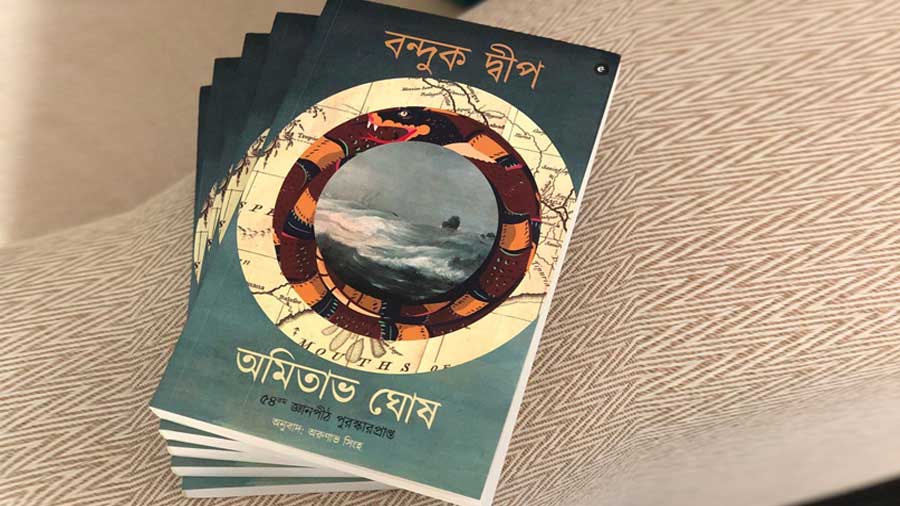

MK: You’ve just finished translating Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island into Bangla. But you don’t usually translate to Bangla from English. What changed?

Arunava Sinha: I just wanted to take it up as a challenge — for two reasons. First, I wanted to challenge my head more, because as you grow older you need to throw higher obstacles in the path of your mind so that you stay more alive. Secondly, translating to Bangla makes you start thinking like a writer in Bangla, as opposed to a reader, and that’s a whole new ballgame.

[‘Bonduk Dweep’, by Eka, Westland, can be preordered here. ]

Do you find translating into English easier because you grew up reading mostly English books?

AS: Translating into English is a little easier because I’ve done it more, so those muscles are well-tuned. The first books I started reading were in Bangla. My father’s elder cousin is the writer and poet, Ranjit Sinha, and he had all these books lying around the house. I started reading them, even though they were mainly for adults. Later, my uncle bought me a whole bunch of children’s books, which were called Kishor Sahitya. Bangla is a very nuanced language when it comes to segmenting your life in terms of age. Kishor Sahitya was actually for slightly older kids and I was reading it at the age of five. When I joined Don Bosco in Class I, I discovered the wealth of English books and I switched from Bangla to English almost overnight. Mostly Enid Blyton, of course. But because I read Bangla very early on, it was hard-coded into my reading habit. In retrospect, I realise that I was not just bilingual but genuinely bi-literate from a very young age. In Gun Island, Ghosh states that he read so much that he was completely removed from his immediate environment and he was living in this other world altogether. That struck a chord.

How did you become interested in the process of translation?

AS: When Gabriel Garcia Marquez won the Nobel Prize in Literature (1982), his books became available in Kolkata and I read One Hundred Years of Solitude for the first time. That’s when I had the epiphany that what I was reading was a translation, that Marquez had not written it in English but somebody else had. Around this time, I was also working for a magazine and was given to translate some articles, from Bengali to English, for publication. Later, we started to run a short story and a translation every month, and that was how I started translating fiction. The first story I translated was Rickshawala by Sankar. So, my first translation has been Sankar in every sense. Four years after that, in 1992, Shankar got in touch to say he needed an English translation of Chowringhee for a French publisher. I was delighted. He also paid me Rs. 6,000 for it, which was a huge amount at the time.

Shall we say, the rest is history?

AS: No, no. I moved to Delhi and I forgot all about translations. Life, work, journalism and everything else in Delhi kept me away from it. Occasionally when something like a quarter-life crisis would strike, I would say ‘I must go back to translations’ and I would pick out a book, translate half a page and that would be it. In 2006, when I was pretty much ready to have my full-blown mid-life crisis, I got a call from an editor at Penguin who said they wanted to publish a translation of Sankar’s Chowringhee, and that the author couldn’t remember the name of the person who’d already done it! Since I’d put my name on that first print out, they traced it back to me.

Okay, at this point the rest is definitely history…

AS: Yes. At the Chowringhee book launch, the editor announced that there was going to be a translation of another book by Sankar, so that was going to be Book Two. But in the meantime, in 2008, when Chowringhee won the Crossword translation award, I met Chiki Sarkar in Bombay, who said she was looking for a translation for Valentine’s Day. I told her I was reading a sweet novella by Buddhadeva Bose, where four cynical middle-aged men, triggered by a newly-married, much-in-love couple, recount the tales of thwarted love from their youth. We agreed it might not be suitable for Valentine’s Day. Then a week later, she read Bernice Bobs Her Hair, which is a story by [F. Scott] Fitzgerald and decided she did want that Bose novella. And so My Kind of Girl became book two and The Middleman by Sankar became book three. In journalism, three is a trend; if you’ve done three, then you’re set on a path. I then thought that I’d be quite happy if I could publish 10 translations.

And now you have more than 60?

AS: Not all of them are published yet, but by the time they are, it will be over 70. I’m in my 14th year of translating. Translators have to work very fast because it is not your own voice, so it is like a garment that you put on and you want to accomplish as much as you can before you have to let go. When you’re translating, you absolutely have to steep yourself into the work for weeks at a time. Sometimes you’re quite distracted, and your family will say, ‘Are you on drugs, why are you behaving like this?’

Have you ever tried your hand at writing your own novel?

AS: In fact, the more you read as a translator, the more you realise the magnificence of the literature already out there. You’re very aware of what is good writing and what is not and if you yourself are not capable of it, then you don’t want to add to the noise with some mediocre rubbish.

Which is the most difficult book you’ve translated?

AS: Khwabnama (by Akhteruzzaman Elias) was hard in terms of the language and the sheer grandness of it. I was constantly scared that I would not be able to capture its magnificence because as you read it, you always get a sense that much more is happening in every sentence than just the words would suggest. That is something you can only be sure about by obsessively re-reading your own translated lines to see if it is ringing the same way.

What do you feel about the oft-quoted phrase ‘lost in translation’?

AS: I am completely not a fan; it somehow implies that there is only one version of a story, frozen in stone. Even if you’re reading the text in Bangla, the way you read is not the way I will read it and each of us will produce our own book out of it. All reading is translation and all translation is reading. What does a translator do except read a book very closely and then try to write the same book again in another language? This parameter of lost and gained is irrelevant; it’s not about losing anything, it is diversity.

It’s only recently that translators are getting as much of their due as writers are….

AS: What has happened is, English translations have put Indian literature in the front and centre, so much so that books that are originally written in English are now having to compete for space with these books. Translations are no longer on the periphery.