Not much has remained the same in a Bengali household from the 1960s. The radio has given way to Netflix, cha and adda have been supplanted by WhatsApp groups and emojis, and even luchi and kosha mangsho have had to share territory with pasta and momos. But enter the reading room, and just like the ’60s, you are more likely than not to find a Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay novel tucked away in one corner, with its dog-eared pages a sign of enduring familiarity.

At 86, Mukhopadhyay remains a giant of Bengali literature, someone whose indefatigable passion for the written word keeps on giving. My Kolkata had the pleasure of speaking to Mukhopadhyay at the 2022 Kolkata Literature Festival (KLF), which was inaugurated by him, on the grounds of the 45th International Kolkata Book Fair.

Edited excerpts from a wide-ranging conversation on literature, language and life follow.

‘There’s been no change in motivation from my end’

In his younger days, Mukhopadhyay spent a considerable amount of time moulding Bengali prose to suit his writing style TT archives

My Kolkata: You have been writing for so many decades. Your first story “Jal Taranga” was published in the Desh magazine in 1959. In all this time, has your motivation to write undergone any change?

Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay: There’s been no change in motivation from my end. Perhaps because I’ve always wanted to write in my own way, without imitating anyone. I’ve tried my best to do that. In the first phase of my life, I used to work extremely hard to refine my sentences and syntax, to constantly improve my language. I used to search for new words that would’ve the greatest effect on the reader. During my 20s, I tried to keep moulding Bengali prose to suit my style of writing. That was a time of great rigour and practice for me. With time, themes and subjects have evolved, but then again, they all circle back to life. It’s the same life that everyone from Valmiki to Homer to Shakespeare wrote about. I write about the same life, too, and its stories of love and loss. Nobody can tell a new story, for all stories in the world have been told. All we can do is present an old story with fresh meanings, so that fresh insights can be unearthed from it. That’s what all great writers try to do, and that’s also what I’ve been attempting in all these years.

Sometimes, after writing for so long, I think I need some rest. But then, rest is not a luxury I’ve been able to afford.

‘I never chose to write children’s or detective stories on my own’

‘Nirendranath Chakraborty made me write children’s fiction, something I’ve been doing ever since. As for detective stories, the editorial team at Anandabazar Patrika made me write them,’ Mukhopadhyay said TT archives

You have written in so many genres, including children’s stories and detective fiction. Which has been your favourite genre to write in?

I don’t know if there’s a favourite as such. In terms of my novels, I’ve written whatever has stirred me from within. But I’d like to make a clarification. I never chose to write children’s or detective stories on my own. Nirendranath Chakraborty made me write children’s fiction, something I’ve been doing ever since. As for detective stories, the editorial team at Anandabazar Patrika made me write them. This resulted in me authoring two thrillers (Shada Beral, Kalo Beral and Bikeler Mrityu), something I don’t suppose any other Bengali novelist has done.

‘There was never any rivalry between Sunil and me’

Mukhopadhyay says that he enjoyed a close friendship with Sunil Gangopadhyay despite constant speculation about their literary rivalry TT archives

Bengalis have a habit of creating cultural rivalries, be it ilish versus chingri or East Bengal versus Mohun Bagan. Similarly, in the realm of literature, there has always been a sense of competition between yourself and the late Sunil Gangopadhyay. What sort of a relationship did you share with him?

There was never any rivalry between Sunil and me, at least we never saw it that way. We were such great friends, not just the two of us, but the entire community of writers back in the day, from Moti Nandi to Shyamal Gangopadhyay to Shakti Chattopadhyay, among others. We all wrote differently, but enjoyed great camaraderie with each other. Sunil and I used to work together, and Shakti would often visit, and we’d have endless chats. But we seldom spoke about each other’s writings. Yes, we’d always compliment someone when we read a work of theirs, but our conversations were mostly about cinema, politics or football.

‘I tell filmmakers that they’re at liberty to change my story if they wish to’

A scene from 'Goynar Baksho' (2013), directed by Aparna Sen, one of the umpteen films based on books by Mukhopadhyay

So many of your books have been made into films. How do you feel when your written word is given a cinematic adaptation? Do you feel that you lose some of your creative ownership over a story or that you lose control over your characters?

Cinema and literature are completely different media. The former is objective while the latter is subjective. No cinema can rely entirely on the text, not even Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (based on the novel of the same name by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay). A good director or visual storyteller is someone who’s able to borrow from the book as well as adapt the story to the needs of the screen. This is precisely what I tell anyone who approaches me to make a film out of my book. My stories have probably been converted into cinema more than anybody else’s work in Bengal, and I tell filmmakers that they’re at liberty to change my story if they wish to. So, there’s no obstinacy regarding creative ownership on my part. I have no hesitation doing this because I know nobody will read my book based on what they’ve seen in the film. The book has its own appeal, and it should stay that way.

‘If you stop speaking in Bengali, you start losing your identity’

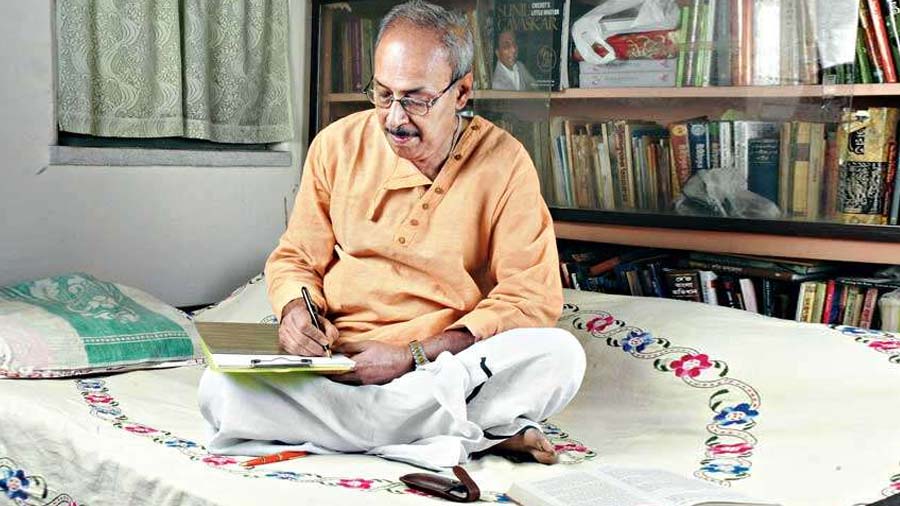

More than youngsters, Mukhopadhyay believes that their parents should realise the importance of learning one’s mother tongue TT archives

We are increasingly seeing youngsters gravitate towards English literature at the expense of their mother tongue, including Bengali. Even though English is the world’s lingua franca, it does not follow that one has to compromise on their mother tongue in a quest to perfect English. What would your message be to young readers who are swayed by English at the expense of Bengali?

Bengalis have always been bilingual. Under British rule, Bengalis had to learn English in order to get employed. For generations, Bengalis have had little problem maintaining proficiency in English without losing their grasp over their mother tongue. But, of late, there seems to be a fashion of not speaking in Bengali and exclusively focusing on English. I admit that it’s important to learn English, for without it one can’t navigate the job market or even explore foreign literature in translation. But it doesn’t mean that one has to sacrifice Bengali because of it. No matter how much English you learn, it doesn’t mean that you lose your Bengali identity. As a Bengali, if you go to America and start speaking in English, you don’t automatically become an American. But if you stop speaking in Bengali, you start losing your identity, and with it the respect that comes from being who you are and belonging to a certain community, a certain heritage.

I remember meeting a young boy recently in America, who had come dressed in a dhuti panjabi to get his copies of my books signed. When interacting with him, I was impressed by his command over Bengali. I asked him if he was from Kolkata. He replied that he wasn’t, and that he had grown up in America. Seeing the surprise on my face, he explained that it was perfectly normal for him to know Bengali even though he was raised in America. He went on to add that a majority of youngsters who speak mostly in English are very much aware of their mother tongue. They simply choose not to use it.

This is where more than youngsters, their parents should realise what’s happening. Of course, it’s wonderful that their children can speak in English, but don’t make them forget Bengali. The two have never been mutually exclusive and there’s no reason for them to be so today.