Gavaskar at 75. Almost sounds like one of those WhatsApp University fakes.

Because he doesn’t look 75. He doesn’t have a paunch. He doesn’t carry a walking stick. He doesn’t have to be helped up from chairs. He doesn’t need anyone to hold his hands when negotiating stairs. He isn’t arthritic.

He speaks with the same intensity. He dissects. He walks 7500 steps a day. He writes with more courage than most. He looks 34. He dyes his hair. He should be awarded a mimicry PhD for his verbal impersonation of Javed Miandad and body swagger articulation of Navjot Sidhu. He carries more than 53 years of Indian cricket in his head.

What is the Gavaskar that I know?

He saved the lives of Muslims during the 1993 riots by running down his Sportsfield high-rise on Worli Sea Face and interceding on their behalf with rioters (turned out that the car belonged to Fakhruddin Khorakiwala, sheriff of Mumbai). A few years ago, he spoke out on the growing communalisation of India. Few did; he was one of them.

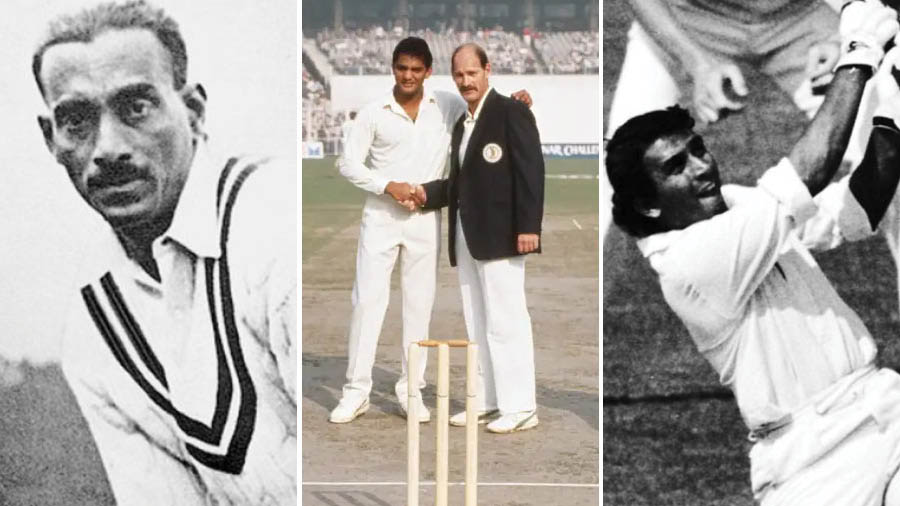

He was the first modern Indian to inspire a world-beating feeling in his individual capacity; he scored possibly more runs than any other batter in a debut series; in a world where virtually every record has been progressively demolished in the last 50 years, this one still stands.

He was the spirit of a nation in the Seventies; each time I stepped off a third-class train compartment in Bombay, my first recall would be ‘This is Gavaskar’s city’. I would think ‘What would Gavaskar be doing now? Where would he be batting? Would he be in a five-star hotel sipping Darjeeling tea? Would he be wearing shades to prevent being identified? Would he be surrounded by bodyguards? Would there be 500 outside his mansion gate?’ I could have substituted that name with A. Bachchan, L. Mangeshkar, DH Ambani and JRD Tata but it was Gavaskar who first came to mind. Always.

He created a legacy of numbers that we associate with a culture of excellence — ‘220’ will always evoke the memory of a Port of Spain and Lord Relator’s calypso (‘But it was Gavaskaah the real Mastah’); ‘221’ will always be a mellow September Oval 1979 afternoon when Gavaskar almost willed India to become the only team in Test history to chase down 400-plus in the fourth innings twice (our second time in three years if we had done it) before Brearley deliberately wasted the minutes and we had to be content with a draw; his ‘96’ in the Bangalore Test match against Pakistan — this TV recording should be put into a bottle for future man to take a correspondence course from — was an exercise in how to bat on a corrugated roof. These are not just numbers; when someone needs me to remember 221 for a business reason, I smile and say ‘Can‘t forget’ and he wonders why.

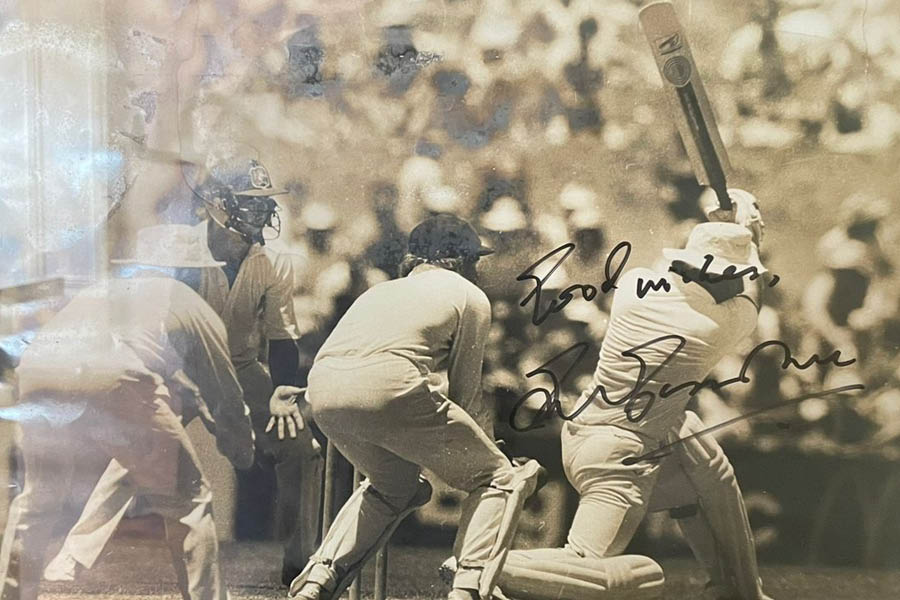

We will never know how good Gavaskar truly was because they never measured the speed of the West Indian fast bowlers those days. He made them look relatively easy. He straight drove Malcolm Marshall (described by Wes Hall as the greatest of all time). A snorter from Marshall knocked the bat out of Gavaskar’s hands in the Kanpur Test in 1983-84 (he hooked Marshall for a six in the following Test) and reached where short silly mid-on might have stood; this would have been an Instagram reel with ten million views today. Like if Mohammed Ali had slumped to the canvas to Foreman in Zaire.

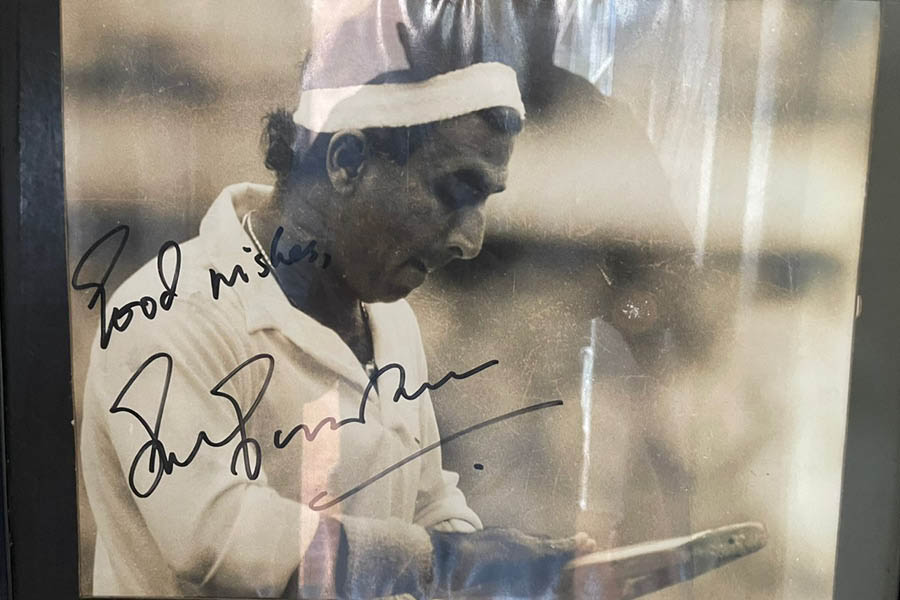

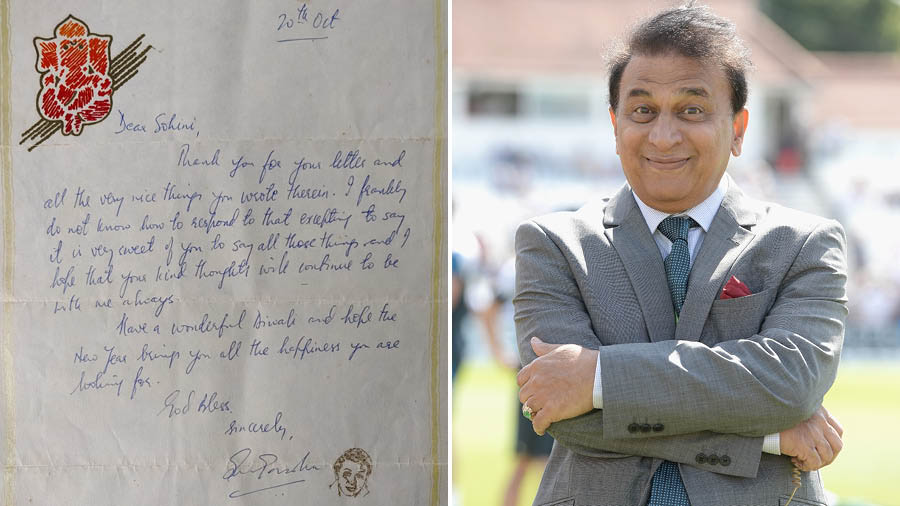

When you wrote to him, he replied in long hand; he wrote a two-page letter when I sent him my co-authored copy of Penguin Book of Cricket Lists. He could have said ‘Thank you’ on a chit and have had it passed to me; he wrote two full pages of fused gratitude, wit, memories and sarcasm (with reference to a Bengal left-arm spinner who felt he had been deliberately under-bowled by SMG).

He retained that maverickness around him; when I asked him to sing a calypso in the shaan of Sanjay Manjrekar after he had scored a double century on the 1989 tour of Pakistan (lyrics written by me), all he said was ‘Take it from me tomorrow’. That evening, SMG converted his hotel bathroom at the Pearl Continental in Lahore into a recording studio. Next morning, he walked into the press box with a cassette (‘Here you are’). I lost that damn cassette. Could have hawked it on eBay for thousands of dollars.

His was the first stirring of the anti-colonial in the modern post-Independence generation; he refused the MCC membership when it was first offered because he had once been barred from entering Lord’s even though he had a pass on him. In later years, his columns dripped with this refreshing anti-colonial ink when the rest of the country sought to toe the line.

He had a mind of his own; he gave his retirement scoop to a vernacular Calcutta paper (Aajkal) when he could have convened a press conference attended by worthies extending from The Times to The Guardian to The Hindu to The Times of India. He was cocking a snook at the world; SMG made it public a good 24 hours after Debashis Dutta run panting to a public telephone in London to get word through to his paper in Calcutta.

He refused to play in Calcutta after his wife and he were pelted with orange peel after he was dismissed for none in a Test match, the general version being that he had thrown his wicket away (the irony was that his son played for Bengal in the Ranji Trophy).

He once dropped himself in the batting order — cosmic aberration — in an unsuccessful series against the West Indies. Before that the word was that he wasn’t trying hard enough because Kapil was captain. Between one of those Test matches, Kapil and he were ‘summoned’ for an audience with the BCCI president. I will never know what transpired in-camera but in the following Test he scored his highest ever (236 not out). At number four. Dujon asked for that bat. And Gavaskar gave it away. Just like that.

He attested the Australia emigration forms of a Sportsworld colleague by writing out a nice reference even though the magazine had taken a consistent anti-SMG stance through the Eighties.

He nonchalantly shunned the helmet (‘The skull is harder than the ball,’ he dismissively answered) and there is a legendary story of how in the middle of a Georgetown Test he took Malcom Marshall in the middle of the head, stood erect, did not ask for pavilion ice and saw the ball ricochet 15 feet towards the bowler (presume Marchall walked down, and tipped the ball up with the toe of his boots and caught it mid-air and walked to his run up hissing ‘Funny maan.’). No West Indian stirred from slip or silly mid off to condole; they waited to see if Gavaskar would ‘break’. Next ball Gavaskar straight drove before Marshall could stoop to stop; he moved from 49 to 53 when he should have lying under the X-ray screen in the hospital.

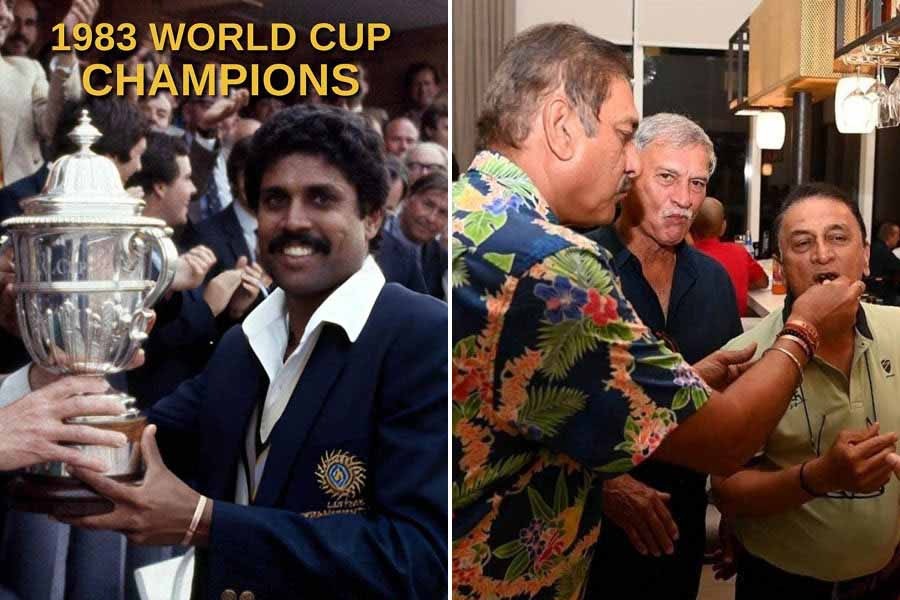

He raised Kapil Dev’s hand on the Lord’s balcony after India won the World Cup in 1983 (like they do with boxers when the other guy is lying on the floor seeing stars) and suddenly the gossip writers lost a story.

He scored a century in a one-day international during the World Cup 1987, including a reverse sweep that went to the boundary (triggering a national pre-social media debate on whether someone of his calibre should have stooped to this level).

He was — and is — a law unto himself: batted left in a Ranji Trophy final, walked off the ground with his non-striker after being given out LBW in Australia, helped create a pressure group that asked the BCCI for a higher remuneration, petitioned the Indian government that all retired Indian sportsmen be paid better, created an NGO that sends out monthly cheques to them 37 years after he played his last Test, requested veteran Indian cricketers for autographs during the Jubilee Test of 1980; requested Dhoni to autograph his shirt in public a couple of years ago.

The man still has lots to offer. If I was feeling low and had his mobile number, I would have sent him this message: ‘Please talk like Viv Richards for me.’

If I could only convince him to do a series of conversations of his playing days — where he does not need to write and only needs to speak — the output could be a seminal archive on the ‘Brazil of cricket’.

In five years, when he is 80 and still white hair-less, and just as busy spinning around the world with his hat on and talking cricket live with maidens his daughter’s age, they could still put pads and gloves on him and get him to star as lead actor in a film on the life and times of Sunil Gavaskar.