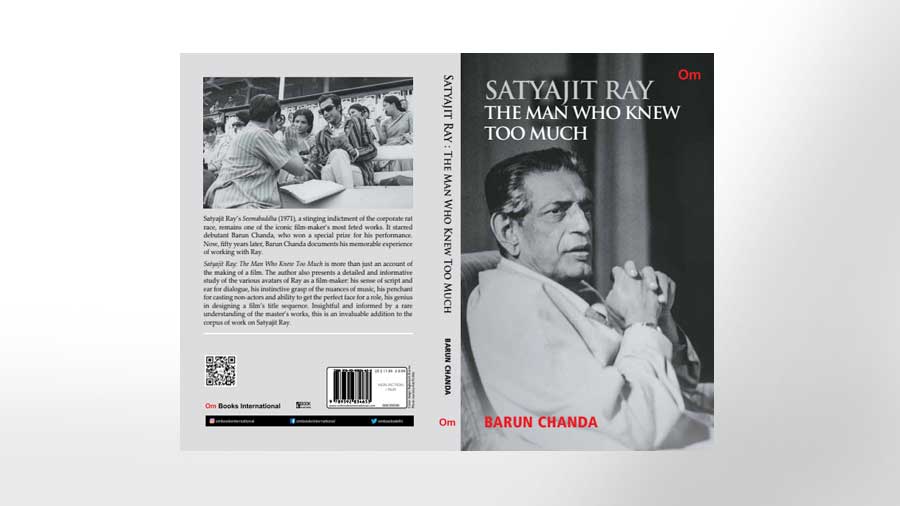

As the world celebrates Satyajit Ray’s hundredth anniversary, Barun Chanda, who starred in Seemabaddha, documents his experiences of working with the master. In breezy anecdotal style, the author provides an up-close and intimate account of the making of an Indian classic – from its casting to its release – and the relationship between one of the world’s greatest directors and an actor making his debut. But Satyajit Ray: The Man Who Knew Too Much is more than just an account of the making of a film. The author also presents a detailed and informative study of the various avatars of Ray as a film-maker.

In this excerpt from Satyajit Ray: The Man Who Knew Too Much, published by Om Books International, Barun Chanda writes about how Ray handled his actors.

***

One of the most distinguishing features of Ray’s direction was the way he handled his actors. I’ve talked to a number of them. And all of them have stated the same thing. He made acting easy for them.

Deep inside his mind did he harbour any theory of acting? We don’t know. At least he never said so publicly. But he did believe in certain dos and don’ts as far as acting was concerned. He wanted acting to be, as far as possible, a spontaneous act. He didn’t believe in overpreparation for any scene before the shooting. He wasn’t in favour of workshops, never used them anyway, even when working with non-actors. He didn’t like his actors to commit their lines to memory. According to him, “Once he’s (the actor) memorized the lines, it’s the hardest thing for an actor to make it sound as if he’s thinking and talking, rather than just mouthing the lines. So, it’s (my dialogues) written like that, with a very plastic quality which has its own filmic character, which is not stage dialogue, not literary dialogue. But, it’s as lifelike as possible, with all the hems and haws and stuttering and stammering.”

He did rehearsals, “but not very much”. “There’s a first rehearsal when I’m not behind the camera, when I’m just watching the whole thing for all the details of acting. And just before the take, if it’s complicated, I have at least two rehearsals when I’m on the camera to see whether I can actually do it … I wait for everything to be ready. I rehearse (only) after the lighting is finished. And immediately after the rehearsals I have the take. Immediately. While it’s fresh in their hearts.”

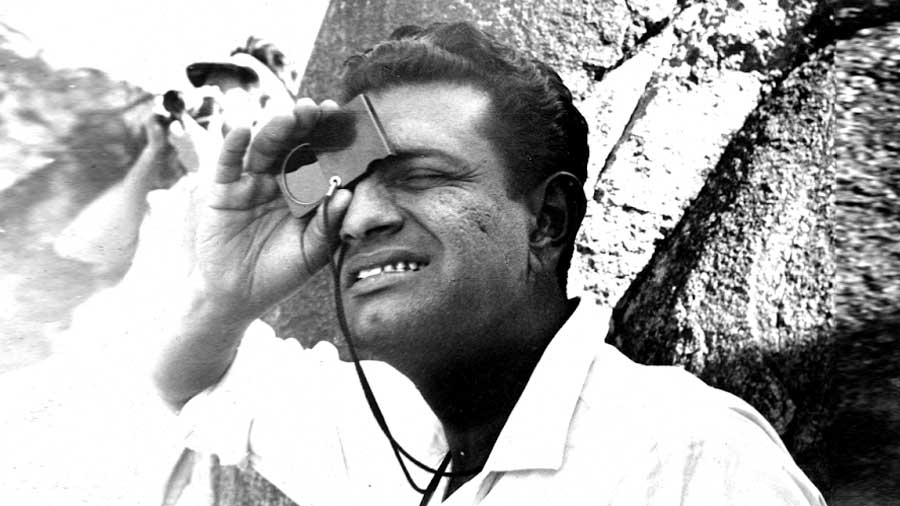

'Nayak '

Uttam Kumar in a scene from 'Nayak'

… the closest [Ray] has come to expounding his own notion of what constitutes good acting, comes from one of his own characters, Arindam Mukherjee, in the film, Nayak. Since the story, script and screenplay of Nayak are all credited to Ray himself one would be tempted to think that the protagonist’s thoughts and beliefs, expressed in the film, largely reflect his own opinion.

There is Shankar-da, a committed theatre person who hates films. According to him films have nothing to do with art. And a film actor is nothing but a puppet, a puppet in the hands of the director, in the hands of the audience and in the hands of the editor. Arindam doesn’t agree, but lacks the courage to say so. …

Arindam’s confrontation with the older, more famous actor of the day, Mukunda Lahiri, brings out Ray’s theory of cinematic acting into sharper focus. Deep inside, Arindam can sense that actors who go on delivering the same things over and over again – same voice, same delivery, same mannerisms – are doomed to failure. “You can’t overact in front of the camera. Just a little exaggeration would get magnified ten times.”

There is little doubt that, in these words, Ray was actually voicing his own convictions.

But, while he was against all forms of exaggerations, or ‘staginess’, he was not necessarily against stage actors. Indeed, some of his most well-known movies owe their success to stage actors like Chhabi Biswas, Utpal Dutt, Pahari Sanyal, Rabi Ghosh, Santosh Datta and, of course, the inimitable Tulsi Chakraborty.

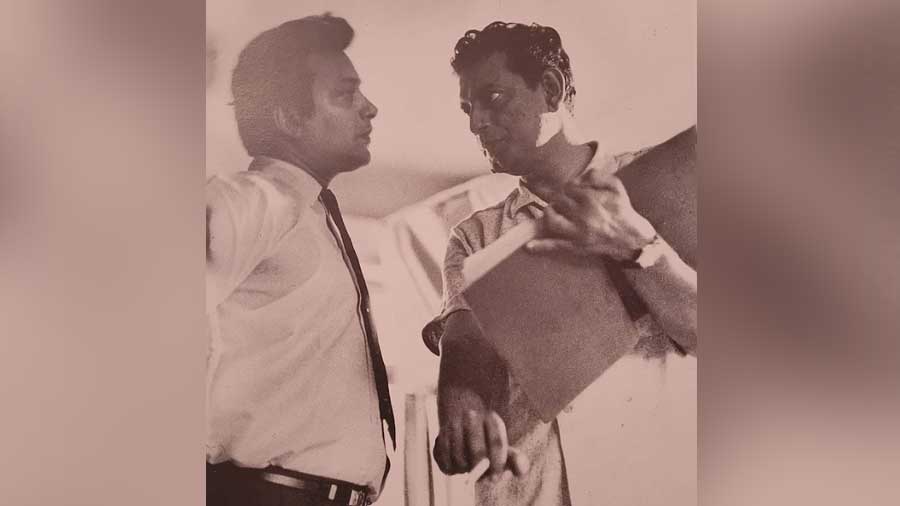

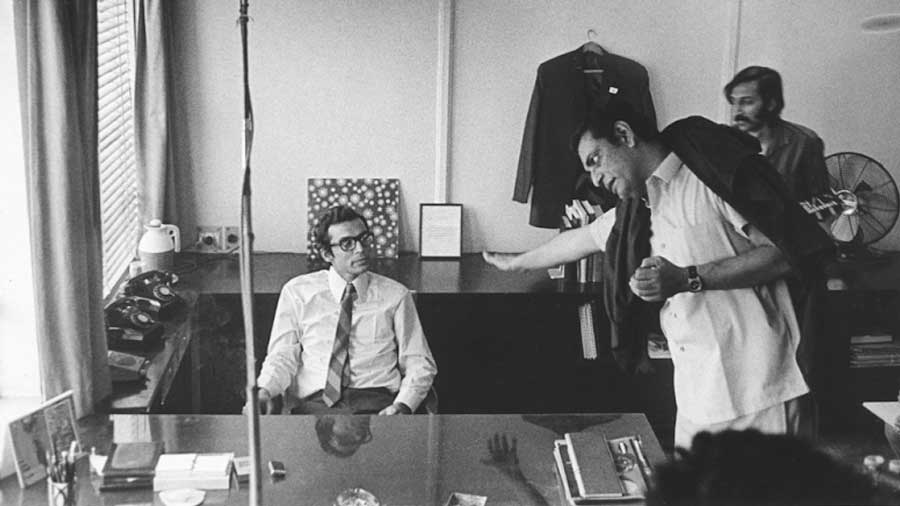

'Seemabaddha'

Ray directs Barun Chanda in ‘Seemabaddha’

… I, for one, can speak about my role in Seemabaddha in some detail. Before the shooting started, Ray had called me over one day. He said that since I had been selected as Shyamalendu, he took it for granted that I knew what I had to do as an actor. But, should my acting ever run contrary to his idea of the role I would have to follow his dictate. That had seemed to me a ‘given’. There couldn’t be any debate on that.

But, to come back to the question of why he never gave me the script of Seemabaddha, while the shoot was on. Perhaps, it had stemmed from a fear that I would remember or ‘memorise’ my lines in advance and that would mar the naturalness of my acting. And this is how he explained it to me.

“Listen Barun,” he told me, “if I ask you a question you would take a little time before answering, won’t you? Because you don’t know the answer in advance. Now, if you memorize the lines, that answer would tend to come too pat, too quickly perhaps. I don’t want that to happen.” He took a pause, then carried on. “I want you to give that little bit of time to think, before you answer.”

“But, what if I forget the line?”

“No problem.” He smiled back. “Of course we will rehearse the scene before taking the shot. After that there will be a ‘monitor’. (A monitor is a precursor to the actual take, with all lights and camera movements.) And, if after all that a mistake occurs we will take that shot again. So, what’s your worry?”

This is how Ray would put me at ease.

'Jana Aranya' and 'Kanchenjungha'

… I have talked to two other Ray actors on this issue of memorizing. One of them is Alokananda. The other, Pradip Mukherjee, the hero of Jana Aranya. Both of them averred they had been told by Ray not to memorize their lines. As for Alokananda, I was glad to hear that she, too, hadn’t been given a written script. Ray had apparently come over to their place one day to read out the script to her and had left with these words, “I’m not leaving any script behind. Your lines are sparse. And I don’t want you to memorize them. All I want you to do at present is try to understand the girl, Manisha, try and get under her skin.” Alokananda tells me that the only guideline Ray ever gave her during the shooting of Kanchenjungha was, “Take your time. Don’t hurry through your lines.”

Regarding ‘staginess’ in acting, Pradip reminisced, on rare occasions Ray would come close to him after a take and whisper into his ears, “No staginess. Let’s do it again.”

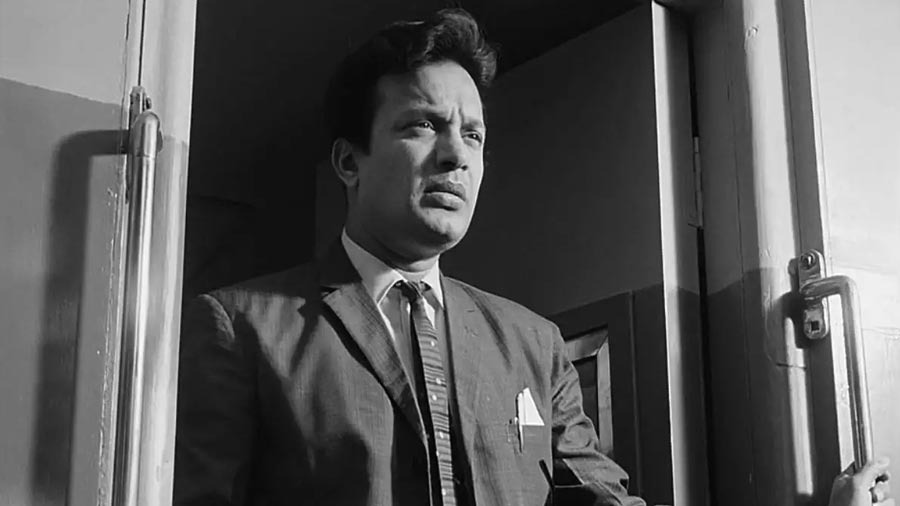

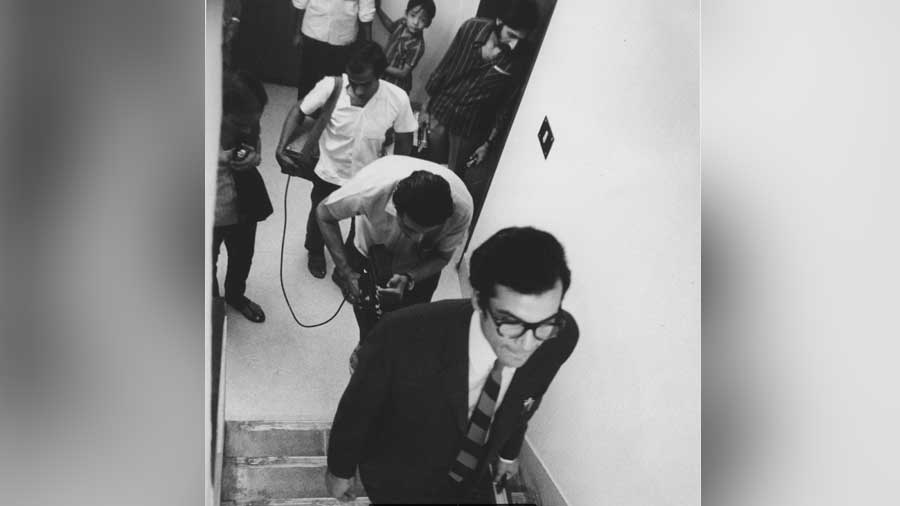

'Seemabaddha'

Another scene from the shoot of ‘Seemabaddha’

…During the shooting of Seemabaddha there are two incidents that clearly stand out in my mind as examples of Ray’s great sensitivity in dealing with his actors, as well as his deep psychological insight.

The first one took place in one of our office sequences. …

The incident that I recount here happened on a Saturday. I had a scene with Harihar Talukdar, our personnel manager, enacted by a guy called Ajay Banerjee, who also happened to be a professional stage actor. I think it was a little past 1 p.m.

As we started rehearsing the shot at my office, Ajay started fumbling with his lines. This was unusual, because Ajay was a dependable actor. What made matters worse was, with each passing rehearsal his nervousness kept increasing. He was not only fumbling now, but stammering as well. And the shot involved Talukdar borrowing a cigarette from my packet on the table and lighting one, while speaking his lines. In no time at all the ashtray on my table was choked with the butt ends of his cigarettes. And still the ‘take’ didn’t come through. This was supposed to be the last shot before lunchbreak. Ray kept looking at his watch. Normally, he announced lunchbreak at 1 p.m.

Suddenly, Ray stopped the shooting.

“Arey, Ajay! Don’t you have a show at Rang Mahal today in the afternoon?”

Ajay lowered his head and muttered, “Yes, sir.”

“What time does it start?”

“At 3 o’clock, sir. But, I’m required to be there latest by 2.30 p.m.”

Rang Mahal, a theatre house, where Ajay regularly appeared as an actor, was some distance away. It was also his bread and butter.

“And when is the show over?”

“At 5.30 p.m., sir. But my part should be over by quarter to four.”

“Oh great! Do you think you could come back here by 4.30 p.m., then?”

“Yes, sir.” Suddenly Ajay was beaming ear to ear. “I can certainly manage that.”

“Okay … lunchbreak,” Ray announced. As Ajay was hurrying away, Ray called him back.

“Don’t go without having lunch.”

Ray knew that they didn’t serve lunch to the actors at Rang Mahal. If Ajay left now he would have to go without lunch for the day.

When Ajay returned after completing his assignment at the theatre, it was just a little after 4 o’clock. And, miracle of miracles, the very first ‘take’ was an okay shot. He was on fire that evening. Every shot, first ‘take’ okay.

Now what would you call Ray for that? A very perceptive director, a great humanist or, a very good psychologist?

Right faces for his characters

… Ray had an unerring eye for selecting the right faces for his characters. Which is why his films seem to be inhabited by real people, not actors. Take the character of Ramalingam in Seemabaddha, for instance, the guy who spouts Joseph Conrad at the drop of a hat. In real life, his name was G.V.R. Murthi, if I am not mistaken, and he happened to be the advertising representative for the newspaper, The Hindu, of Madras. He was a true Tamilian and looked genuinely so. After the commercial release of the film, G.V.R. Murthi became a sort of an instant celebrity. Everybody singled him out as a fantastic find, a natural actor.

Ray’s films seem to be inhabited by real people, not actors

Unfortunately, acting wasn’t his forte in real life. Ray learnt the bitter truth once he started the scenes with him. Murthi was comfortable only doing the lines in Tamil, nothing else. But the Tamil portion in the dialogue had to be explained to the audience. Preferably in Bengali. That’s when the problem surfaced. Murthi, in spite of spending years in Calcutta, couldn’t speak Bengali to save his own life. I thought Ray would be forced to change his cast and get someone who acted better. Or, at least whose Bengali was.

That’s when I saw a totally new side of Ray; his determination not to give up and his dogged perseverance to carry on till he had got things right. It was as if he would be letting himself down by changing the cast, tantamount to accepting defeat. As a director he couldn’t do that.

All this while, I was watching him fascinated. How was he going to surmount the problem now? And this is what Ray did.

“Mr Murthi, forget the lines. Can you speak just these three words?”

Fortunately, Murthi was able to do that. So, Ray broke up Murthi’s lines into separate components, each component not more than three words, at times just two words. Somehow Murthi managed that.

I was wondering how on earth Ray was going to manage it on the editing table. I needn’t have. He took my silent reaction shots for the entire part of Murthi’s dialogues. On the editing table he had a silent reaction shot of mine after every few words of Murthi. That’s how he managed the scene. In the film it looked fine and Murthi came out as a brilliant actor.