I wasn’t 12 yet. The hallowed home where Nobel Laureate Thomas Stearns Eliot spent some of his life, with his wife Valerie, is a hop, a skip and a short jump from Buckingham Palace. As we turned the corner from Jermyn Street, we were there. I was too young to appreciate the visit. But decades later, as I became a student of his craft and his passion, I recalled the row of books I had seen in Eliot House as a young girl that cold November day at Mason Street.

Now, while I meditate and write about 100 years of what must arguably be the most discussed poem of the last two centuries, inside and outside the global academy — The Waste Land — I am transported to the complex, challenging and fascinating life of an exceptionally gifted poet.

Eliot, the recipient of the Nobel in 1948, had a conflicted life in so many ways. He seemed, like Ezra Pound, Virginia and Leonard Woolf, George Orwell, Graham Greene and so many others who are known as Modernists, to be torn asunder by battles on the battlefield and within, about power, moral decrepitude, religious faith, marriage and relationships — pursued by the spectre of a blasted heath, a wasteland that all of Europe had shrivelled into, since the First World War.

It was in London that Eliot met the movers and shakers of the Modernist movement in literature, music and the performing arts, and came under the watchful gaze of his contemporary, the influential Ezra Pound. Eliot’s relationship with Pound was somewhat like R.K. Narayan’s equation with Graham Greene. Both Pound and Greene had the respect and gravitas to mentor and aid colleagues who had the promise of success as outstanding writers.

The house where Eliot lived in London

Vivienne Haigh-Wood Eliot (exteme left) and T.S. Eliot (extreme right) with friends in December 1931.

Vivienne Haigh-Wood Eliot photographed in 1920. Picture: National Portrait Gallery, London

Pound helped Eliot in the publication of his work in several magazines, such as The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock in Poetry magazine in 1915. Eliot’s first book of poems, Prufrock and Other Observations, was published in London in 1917 by The Egoist, and immediately established him as a leading poet of the out-of-the-box. With the iconic The Waste Land (Boni & Liveright) in 1922, which stands as the most spectacular piece of poetic genius, Eliot transformed himself into a world poet of mythic proportions.

Eliot was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on September 26, 1888, and was a resident there during his early years. He studied at Harvard University and got himself a Bachelor’s degree and wrote poems for the Harvard Advocate. After a year at the Sorbonne, he returned to Harvard to study for a PhD. Then, he moved back to Europe and resided in England since 1914, the first year of the First World War. The following year, he married Vivienne Haigh-Wood and began working in London, first as a teacher, and later as a banker for Lloyd’s Bank.

The painful relationship between the American-born poet and his first wife was the subject of the 1984 play Tom and Viv, and later a film of the same name which I recall being very disturbed by. After I experienced Thomas “abandoning” Vivienne as a “mentally unsound woman”, I battled days of sadness. His leaving Vivienne at such an early phase in their marriage without having given her more patience and attention often found me, as a devotee and a reader of Eliot’s works, confused and saddened.

There is a concluding scene in the film Tom and Viv where Eliot leaves Vivienne in a mental asylum. Alone, she is more devastated than ever. My swaying between wrath and unbidden sympathy for Eliot persisted and still persists as I see him as a dysfunctional man in almost all the relationships he attempted to have with women, or vice-versa.

American poet and composer Ezra Loomis Pound, who edited Eliot’s The Waste Land. Picture: Getty Images

Early in their marriage, Vivienne, who was cherished and befriended by Bertrand Russell, was extended the understanding and attention she missed from Thomas. She had an affair with Russell, which Eliot had not reacted to. It is no secret that Vivienne told their friends that Thomas and she were incompatible and Thomas told friends he felt uncomfortable in her presence.

In 1928 he took a vow of chastity and initially wished for a separation from Vivienne in 1932. He then took up a professorship at Harvard and met Vivienne only once in 1947, before she died.

In the US, the poet with gravitas and charm, Thomas Stearns Eliot, had a line of admirers. And since it was well-highlighted that he was not in a typical marital relationship with Vivienne, many women came into his view. Emily Hale, a drama teacher, befriended him in the ‘30s. Then, for a couple of decades there was a platonic relationship with Mary Trevelyan, but the poet had a bitter taste of marriage, which he explained was a “nightmare”.

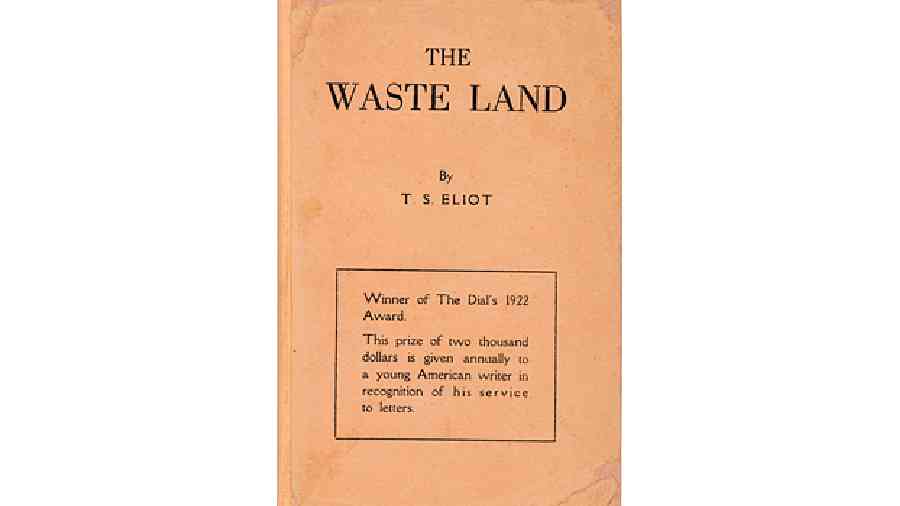

An early edition of The Waste Land

Eliot with his second wife, Valerie on their honeymoon in 1957. Picture: Getty Images

Much to the surprise of most of Eliot’s friends, he married his 30-year-old secretary, Valerie, in 1957, when the poet was 68. Valerie had worked for him for eight years and was meticulous in her archiving of his unpublished letters and manuscripts for decades after his death. Just over a decade ago she initiated and encouraged a publishing project of his letters which she preserved and organised with great care and love.

Now, as I leaf through the collection that validates Valerie’s single-minded devotion to preserving this titanic poet’s legacy, I seem to have gone a step towards understanding a little of how this great poet himself was broken apart when he put his first wife in an asylum.

As he said in a letter: “I don’t know what to do. I am frightened.” T.S. Eliot was much more than a poet. He was the blind Tiresias, the drowned Phoenician sailor, he was Macavity the mystery cat, that he wrote of. But more than all this, he was a man who was riddled by the same bullets that we all encounter daily. And so we must celebrate.

Finding new messages in The Waste Land after a century

“April is the cruellest month, breeding Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing Memory and desire, stirring Dull roots with spring rain.” — T.S. Eliot in The Waste Land

Arguably the most analysed, deconstructed, celebrated, overwhelmingly influential poem of the last hundred years is Nobel Laureate Thomas Stearns Eliot’s The Waste Land. Americanborn Eliot, who had famously stated, “Our beginnings never know our endings”, was known as a Boston Brahmin, having deep and abiding ties with Harvard University, from where he earned his doctoral degree and later a professorship.

He sank his roots in England in 1915, the year he married his first wife Vivienne. Her mental state which led to her acute suffering and her progressive deterioration after 1925, bordered on bipolar disorder and paranoid schizophrenia. This caused her to be aggressive. Although the poem The Waste Land has often been seen or read for over 90 years as the desert that was created by the First World War and the death of joy and the loss of fertility because of its horrors.

Its inception, however, is now being traced to the blasted heath, the turmoil of Eliot’s marriage to his first wife Vivienne. This is a significant shift and it happened after the publication of the 1932-1933 letters some years ago, thanks, ironically, to T.S. Eliot’s second wife Valerie, who meticulously and professionally archived these unpublished letters.

In February 1933, Eliot wrote to his friend Alida Monro that “the whole history” of life with Vivienne had been “a hideous farce”.

According to the editor of the collection of this volume’s letters, John Haffenden, “It’s a pretty harrowing period for both parties. Eliot biographies have versions of this story, but they certainly didn’t have access to everything.” He pointed out that letters show that “Eliot feels guilty as much as he feels reproachful” and that Vivienne just “doesn’t quite get it”. “She doesn’t understand why Tom won’t come back to her.”

Vivienne’s sense of loss and loneliness, her inability to deal with the horror of not being able to cope, drove her to dire straits, especially after she began to lose her husband’s love and company. Author Virginia Woolf described her in 1932 as a “poor raddled distressing woman, takes drugs”. Vivienne had been committed to an asylum/s for 10 years before she died in 1947. She was 58 at that time.

Eliot married Valerie. She died in 2012, but worked hard to make Eliot’s letters — at a most troubling time in his life —accessible to readers. In the latest volume’s introduction, Haffenden maintains: “Valerie hoped that, while facts relating to her husband’s first relationship were scarce, the public could at least have knowledge of all his thoughts relating to the period. Valerie was also adamant that Vivienne’s point of view should be given air.”

The Waste Land has five parts — The Burial of the Dead, A Game of Chess, The Fire Sermon, Death by Water, and What the Thunder Said. What of the title of the poem itself? As one reviewer and critic points out — “Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal.” Eliot wrote, and, as with Macavity, the master criminal in his Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats (1937), you can’t always tell where the poet’s been.

It could be, in this case, that he stole from Tennyson’s The Passing of Arthur, and its undulating mood — “as it were one voice, an agony / Of lamentation, like a wind that shrills/ All night in a waste land, where no one comes,/ Or hath come, since the making of the world.”

Most of T.S. Eliot’s critics and readers see The Waste Land as a representation of the impotence and infertility of the aftermath of the First World War, whence the poem is chronologically situated, and the splintering of an entire global civilisation.

In a recent discussion in a Master’s classroom, when I asked the scholars what was the most powerful image that accosted them, almost all five students who responded said that the poem The Waste Land was vividly expressing the urgency of an ecological disaster. “The entire poem is a cry for water”, said one scholar who quoted: “I will show you fear in a handful of dust.”

As she explained very wisely for a 22-yearold: “We can read the word dust as a warning — of our death: ‘from dust were ye made and dust will ye be’; or we could interpret dust as a barren landscape which we have raped and plundered, and nothing will grow, literally, as with botanical erasure; we can read dust as the dust we have to taste during war, military battle where we taste the metal when machine guns are firing and dirt as the dust pervades our tongues. But mostly our generation might wonder whether Eliot was speaking of the dryness and barrenness between human beings and the lack of nurture in our ability to love and be loved.”

For those of us who return to our most favourite poems to receive peace and succour in times of grief or frenzy, The Waste Land is a song for the soul.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance ofLife and co-author of the bestselling biographyStrongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen.She has a PhD in English and South AsianStudies from the University of Toronto, where shetaught World Literature and PostcolonialLiterature for many years. She currently lives inCalcutta and teaches Masters English atLoreto College