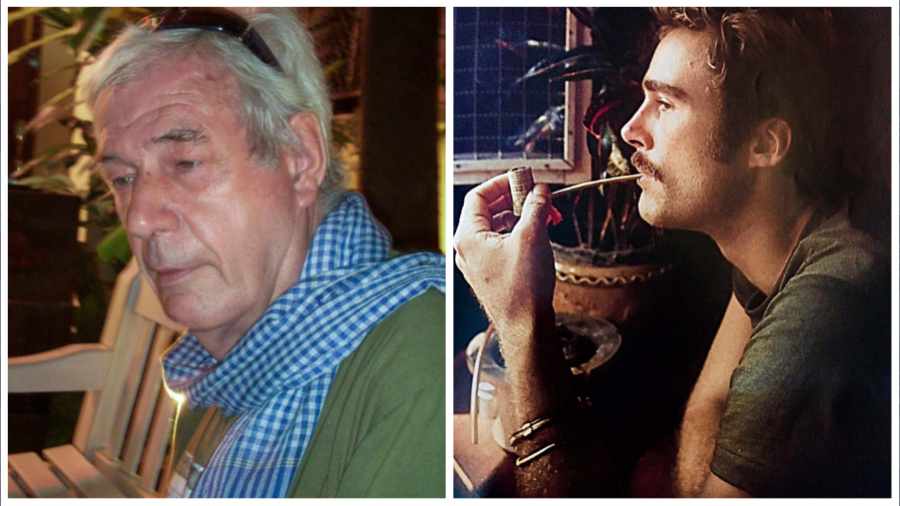

Friend and mentor, the legendary combat photographer and bestselling author, Tim Page, 78, died battling cancer on August 24, at his home in Bellingen, Australia. Page catapulted to fame with his visceral images of the Vietnam War (1954–1975), and literally came back to life after being declared dead on arrival at a hospital in 1969 during the war.

Feisty with a whacky sense of humour that helped him through some life threatening moments and his long and illustrious career, Tim Page’s passing has dampened spirits of his younger colleagues, followers and champions worldwide. Born in Tunbridge Wells in Kent, Page was an orphan with a guardian angel looking after him. He lived in his early years in Orpington, UK, but the wanderlust hit him early. In 1962, he made it overland through Europe, as a cook, then Pakistan, India, Burma, Thailand and Laos, empty of pocket but hugely inventive. In Laos, he got himself employment at USAID. He was not even 20 yet. He had married at 17 and got divorced at 18. Believing in the triumph of hope over experience, Page would marry thrice in his life. And is survived by one son, Kit.

Many of us, who were correspondents or writers, were revisiting the history of Vietnam and Cambodia and reformulating the idea of Indochina — Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos — in the 1990s. The new crop of our generation of scribes and the old guard idols like British combat photographer Tim Page and American Al Rockoff were in a memorable confluence in Phnom Penh in 1993 even as Khmer Rouge stalwarts who had been the killing machines of the Pol Pot genocidal regime were on the run, hiding in the remotest places like Battambang on the Thai-Cambodian border to escape trial for war crimes.

Long after the Vietnam War was done and dusted, I made my first foray into Phnom Penh to begin my research for the book Dance of Life: The Mythology, History and Politics of Cambodian Culture that would be published in 2000 — about the handful of survivors of Cambodian classical dance from the murderous Khmer Rouge regime. In Phnom Penh, in the midst of literally thousands of blue uniformed UN peacekeeping forces, journalists and some interested Vietnam War veterans and hippies who had arrived from lonely and far-flung places from across the planet to participate in the circus, I was introduced to a devastatingly handsome face that I knew from celluloid and print.

“This is Tim Page,” someone introduced me.

“ So la-di-da. You look like you don’t belong here,” said the devilishly handsome face with a wicked smile.

That was the beginning of a friendship that was abiding, and as adventurous as it was strong. Tim was acutely well informed, unstoppable and had a whacky sense of humour — all great qualities for a good teacher. I was seeing in the flesh the resurrected man who had suffered a terrible head wound and innumerable blast injuries and had scared the wits out of a mortuary attendant at Long Binh Army hospital in Vietnam in 1969, when he had suddenly declared “Am I dead yet?” Every time we met over the next many years, he would remind me that he had plastic in his skull, so he was well repaired, and that I was to respect the walking technological marvel that he was.

Generally acknowledged the guru among photojournalists who covered the Vietnam War, Tim Page has six books to his credit — including his bestselling autobiography Page after Page (1988) as well as majestic photospreads in Life, Time, Paris Match, Rolling Stone and other leading magazines. His other books — Tim Page’s Nam, Sri Lanka, Ten Years After, and Midterm Report — are all powerful, meticulously documented and innovatively narrated works that have arrested readers with their touching accounts of momentous events in Asia. War, peace, humans and the planet in turmoil are all subjects that Page has captured in unique and unexpected ways, looking through the lens as only he could.

After that first encounter, when we returned to Singapore where we were based at the time, Tim came to visit many times — and later in Bangkok too. We remained in touch for a long time, and he wrote the introduction to Cambodia Silenced: The Press Under Six Regimes, the book my partner and Indochina specialist Harish Mehta published in 1997. Once, Tim turned down an offer at a meal at the opulent Ruen Thai restaurant at the Hyatt Erawan in Bangkok where we had invited him for dinner insisting that we go with him to a Laotian restaurant in one of the sois at the derelict backstreets of old Bangkok. There he taught me the way to mould sticky rice cylinders, dip them in Issan-style chilli dip and pop them in the mouth without getting my fingers wet.

At first, I was irate at a White man telling a Bengali girl how to mould a rice ball. But his charm and disarming humour quickly got me appreciating the warmth and cultural knowledge he had acquired over decades in Southeast Asia. And he was wildly possessive, in a caring sort of way. At lunch once at the Wheelhouse café at The Tanglin Club in Singapore, as I was about to dig into my favourite creamed spinach, he whispered in my ear, “Oh, how can you eat that parrot vomit? It’s so much more fat than spinach, with all that cream. It really isn’t good for you.” That image stuck with me and I must confess I have not been able to look at creamed spinach ever since.

Another time, before the mobile phone had intervened so assertively in our lives, as a bunch of friends sat chatting one afternoon when Page was visiting Singapore, I was told by the restaurant that the author Ben Okri was calling for me long-distance from London. On my return to the table, Tim had a big beam on his face. “So who is this okra who is calling you?” he asked, hoping to get me all worked up. That’s the kind of informality and affection you were lucky to receive from Tim.

He was never pretentious, never barbed in his engagement. If he cared for you he would treat you with familiarity and collegiality, and you would do the same. Later, I discovered that Michael Herr, a close friend and admirer, in the incomparable book Dispatches had written way back in 1968 that when you were friends, Page did everything for you if you needed his help. And you did the same for him. That was the unsaid bond. Once when he was 23 and Herr met him for the first time, he says in Dispatches: “He was broke, so friends got him a place to sleep, friends gave him piastres, cigarettes, liquor, grass. Then he made a couple of thousand dollars on some fine pictures of the Offensive (Tet Offensive battle) and all of those things came back on us, twice over. That was the way the world was for Page; when he was broke, you took care of him, when he was not, he took care of you. It was above economics.”

When Page wrote Derailed in Uncle Ho’s Victory Garden (1995) an account of his return to Vietnam and Cambodia after many years to look for the mortal remains of his soul brother Sean Flynn, it was perfect time to invite him to a ‘meet the author’ event at the historic Tanglin Club in Singapore. The theatrette was packed to the gills with historians, readers, scholars, Vietnam War veterans from all around the globe, who wanted to hear about the war from one of the most outrageously brave and incredible living legends who knew every aspect of that war.

“I had to go back to find Sean,” said Page in his opening line. Charming and exceptionally talented, Sean Flynn was Hollywood actor Errol Flynn’s son who was captured by the Viet Cong, the North Vietnamese resistance forces, and handed to the Khmer Rouge, the genocidal forces of Pol Pot that massacred over two million Cambodians and a number of foreign journalists, diplomats and travellers. The Khmer Rouge then executed Sean Flynn and Dana Stone, a fellow photojournalist.

“After Sean disappeared, I have never been at peace. This book had to be written if only to put at rest the spirits of those whom I knew as family. Sean Flynn was the closest I had to a brother and I don’t think I ever recovered from his death, especially because there was no evidence. It was only after his mortal remains were found when I returned 10 years later (and it took me a long time to write the account) that there was some sort of closure, ” he said to me many times, whenever we spoke of how intimately the Vietnam War had left its scars on Page. And he wasn’t talking about the plastic in his brain.

Page returned to the scene of the crime many times to solve the mystery in the ’80s and ’90s, tracking down places where Sean Flynn and Dana Stone had been, interviewing farmers and peasants in the provinces. Like a murder mystery, in Derailed in Uncle Ho’s Victory Garden, Page systematically tracks and records his single-minded forays into unchartered territory and finally finds the spot where Sean Flynn and Dana Stone were killed.

Page has also been deeply committed to and invested in the Indochina Photo Requiem Project — a commemorative book and exhibition project that showcases the photographic works of the greats like Sean Flynn, Dana Stone and Singaporean Terry Khoo and others who died in the Indochina conflict.

The last time we met was to say goodbye as he was catching the flight from Bangkok to London. His bags were packed, and he was waiting for us at the porch at his hotel to say goodbye before he left. “Time to lock and load. Lock and load, guys,” he said, in his inimitable style, a smile playing at the corner of his mouth. It’s going to be strange not to hear you speak in code to us, a code you taught us and kept us laughing with — “that’s a failed lego building”, “she was hit by the ugly stick”, “oh, that’s Pacific limbless”. As you unlock and unload at your new destination, Tim, we will be turning Page after Page, savouring the memories.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is the author of Dance of Life and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught world literature and postcolonial literature. She now lives in Calcutta and teaches English at Loreto College