We called him (John Mason) “Mousey” affectionately. It was like using a ridiculous nickname for an elder brother. If there was a dose of “public school” humour, the joke was on us. Mr Mason stood upright, strode rather than walked. His eyes twinkled with intelligence and his face hosted a symphony of expressions: it could range from kindly attentiveness, to forbidding power — and everything in-between. Mr Mason always commanded immense respect. But he never let that respect create a China Wall between the students and himself.

Mr Mason embodied the intimacy of a teacher. This was not the intimacy of a confessor figure to who you could confess your deepest desires and secrets. It was more the intimacy of a comrade, a co-learner: one who understood the vicissitudes of adolescence and grew with you as the young mind expanded.

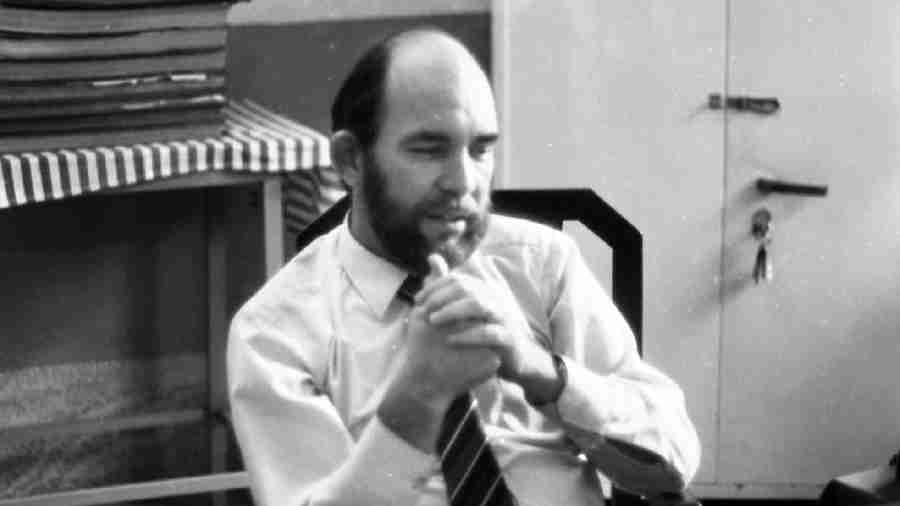

Mr Mason left us on February 17 after a lifetime of teaching in diverse schools. Raised by a single mother, he studied and then taught in La Martiniere, Calcutta; then went on to become principal of St James’ School, which he made into one of the finest in the city.

Always restless, he served as principal of Doon School and Modern School in Dubai; he went on to manage several schools in the UAE. His attainments were many-sided. Not just encouraging sports, he was also active in dramatics, elocution and many other activities (including the NCC) — and of course the arts of administration. He wrote a number of books and engaged in socially active teaching. What I personally recall is the pedagogy he developed in his initial years at La Martiniere.

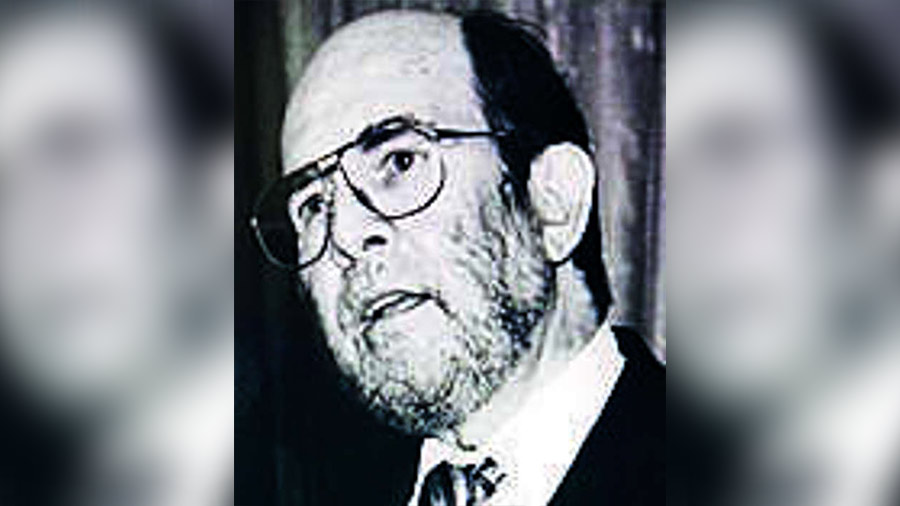

When I first saw Mr Mason in Class VI, I felt that I had already seen him many years ago on the rugby field as a revered senior: he had simply transformed himself into a teacher! The after-glow of a student remained with him — and me — as he became my class teacher in the next few classes till I passed the school. Indeed, even a couple of months ago when I last saw him at the age of near 78, he walked with difficulty. But he dismissed any attempt to help him as if it was an impertinence to even offer a compromise with his sense of independence. He never lost the bravura of a proud, senior student.

His student persona was actually an essential part of his pedagogy. The Calcutta of the late ’60s was a difficult time. The air was thick with rebellion and political opinions. This was constantly manifested in the streets with visible detachments of paramilitary troops, sudden stoppages of traffic as country-made bombs went off somewhere, or when a procession stopped any movement. It was a violent time, a violence that was not calibrated as it is today, but one that could burst out at any moment. Some of us already had strong political convictions and these were lit up by Orwell’s Animal Farm, a prescribed text that encouraged strong opinions. This led to violent exchanges of unreasoned speech amongst ourselves.

Unlike a good Bengali middle-class parent — or a simple teacher — Mr Mason did not shield us from the tumult of the Calcutta streets. In a fairly conservative school, he did something daring. He encouraged us to debate our political opinions in front of the whole classroom and elect those whose opinions carried the most weight. Mr Mason’s pedagogy introduced us to the living heart of democracy. It allowed us to think about issues, rather than trade violent sentiments.

By not offering his own political preferences, Mr Mason created a pedagogic community through discussions. And it extended to political and social values. We discussed the perils and ambiguities of political power through another remarkable prescribed text, Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. Most of all, I recall his classes on Harper Lee’s To kill a Mockingbird. It could have been easily taught as a moral lesson on the evils of racism and that would have been the end of it.

Instead, what he did was something subtle and long-lasting in its effects on me. He wove the race question with issues of parenting and, above all, the ways in which a single father could mother a child in thinking about justice and social conformism, issues that lay at the heart of the novel.

Mr Mason inducted us into the intimacy of sharing a larger world of ideas and values, all of which illuminated our own personal choices.

Another event stays in the mind. Mr Mason had invited a young and famous journalist to our class. Not to pontificate but to discuss two poems, both very modern and difficult. Much to our own surprise, instead of simply turning away in uncomprehending disgust, the class as a whole offered a plethora of interpretations. The famous journalist was besieged by interventions on all sides of the class. By the time the session ended, Mr Mason proudly looked at his friend as if to say, now you know, the value of my vocation!

When I went to college to do my graduation in English literature, one of the issues that dogged us constantly was the question, what is the relevance of English literature in our country? With Mr Mason, we never experienced this as a dilemma. English literature may have been born in different worlds of time and space, but Mr Mason showed us that it was wrapped up in our lives — if we let it. Texts were windows to see into our own lives and values.

Through his literary teaching, I got to love the Englishlanguage as part of my life as an Indian. This was of course the mark of privilege. And Mr Mason did not ignore the question. Indeed, his life was wrapped up in making English accessible not just to the privileged “us” but to extend his love to the ways it could be learnt in different social and cultural locations in our subcontinent.

Among the last things he was working on was to locate folk tales of different regions as entry points into making English more accessible. This was a big-ticket project. In retrospect, it appears to me as a valuable resource. After all, the problems of English learning are common to all learners in an illiterate or semi-literate society. All such learners have to separate out the language they use in their own homes from that deployed for public communication.

Mr Mason’s commitment to his vocation and his society was rich precisely because it avoided the complacency of belonging. Unlike those of us who take our sense of belonging to a culture or a society ora nation for granted, for Mr Mason belonging was an act of working with others. He stayed on in India at a time when many were migrating to foreign lands. Belonging, for him, was always a point of departure into thinking about new areas, extending his expertise, and radiating the vitality of enquiry.

Being privileged to renew contact with him towards the end of his life, I noted a new facet in Mr Mason. This was the quality of asking me ora former student questions about our own expertise, listening intently, and gathering up our knowledge to himself. There was a new element to the peculiar intimacy of a student-teacher relationship. It was as if we have arrived at anew point of departure in now learning from each other.

Death — with its attendant sorrow and regrets — rudely interrupted the freshness— indeed, the ever-renewing freshness — of an intimate relationship. Still, it remains one among the many points of departure in our relationship from school that, as former students, we will, with luck, pass on with our own lives and deaths. The mark of a great teacher is, after all, the ever-renewing pedagogic community he leaves behind him in his students.

Pradip Kumar Datta studied under John Mason from Class VI to Class XI in La Martiniere, Calcutta. A former professor, he taught at the University of Delhi and later JNU.