When I was in the sixth standard in 2012, I discovered Narayan Debnath on a quiet autumn afternoon. It was the designated “library period” in school and all my classmates had crowded in front of the English fiction bookshelf, punching each other over the last copy of Famous Five and Goosebumps. Disinterested in the squabble, I walked over to the Bengali section, which, sadly, in my English-medium school used to remain unfrequented. After a few seconds of visual skimming, my eyes landed on a big hard-bound book carrying two cartoon faces on its cover. I squatted, pulled it out of the shelf and read the title — Nante-Fante Samagra by Narayan Debnath.

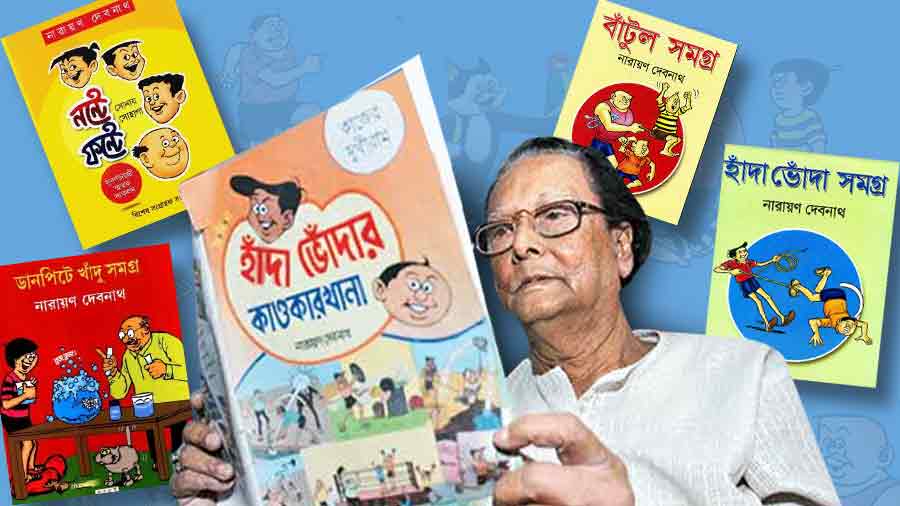

Debnath’s entertaining innocence

My tryst with Debnath and his art started that day, at that very hour which I spent in the library devouring the first 30 pages of the compilation. After looking at plain English texts for hours, the colourful illustrations and the hand-written Bengali served as a much-needed break to my eyes. In between interminable classes, the humour and entertaining innocence of his comics was welcome refreshment. When the library period ended, I issued the book and waited impatiently for the day to get over. I wanted to rush home and finish reading it.

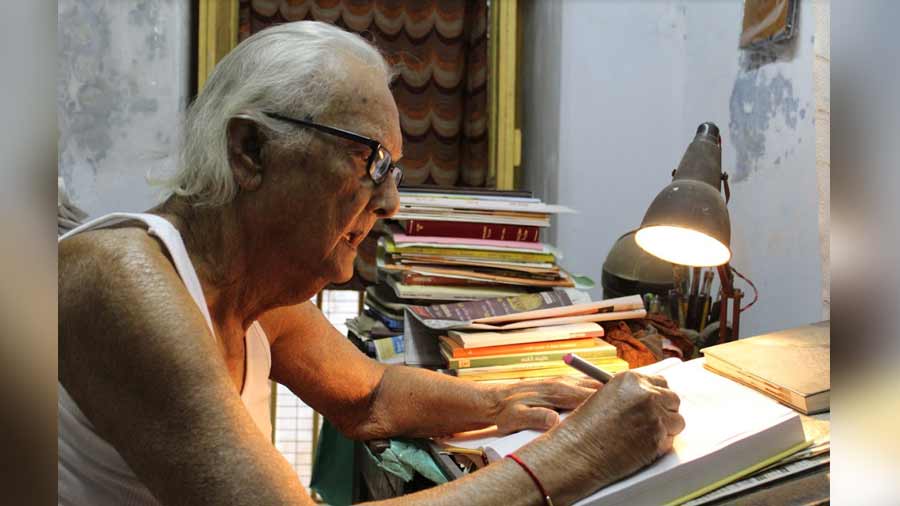

Debnath at his study table, the place where most of his memorable characters were born Courtesy: Hritam Mukherjee

Debnath gifted youngsters with the first Bengali superhero: Bantul the Great, modelled after the acclaimed bodybuilder, Manohar Aich. In the initial years of the cartoonist’s life, Debnath used to sketch his comics in monochrome. His black-and-white sketches of Nante Fante and Handa Bhonda were serialised in the pages of popular childrens’ magazines, Kishore Bharati and Shuktara. Much later, after his comics started gaining prominence, he was requested to use colour. From shading to multi-hue, his works grew more and more vibrant, but the slapstick humour that was a defining characteristic of his comics remained as constant as a pole star.

Debnath’s unique style of drawing thin or bulked-up bodies with slender limbs and a disproportionately large head became a cherished relic of childhood, one which reeked of warmth and nostalgia.

The world of Debnath’s comics was substantially different from the one that I was enveloped in as a child. But instead of that becoming a reason for dissonance, the contrasting realm provided a fantastic allure, inviting me to enjoy comical suffering without any repercussions of reality around me.

As kids, what most of us wanted to escape was the all-pervasive eye of the teacher at school, of a parent back home and Debnath’s world, where mischief will be noticed but not the mischief-maker, made it an ideal destination for mental immersion. And, of course, accessibility was a major factor. Many of my peers were acquainted with Debnath’s works through the preserved collections of their parents’ or elder relatives’, it was a family heirloom of sorts. This was before international comics became as affordable as they are today.

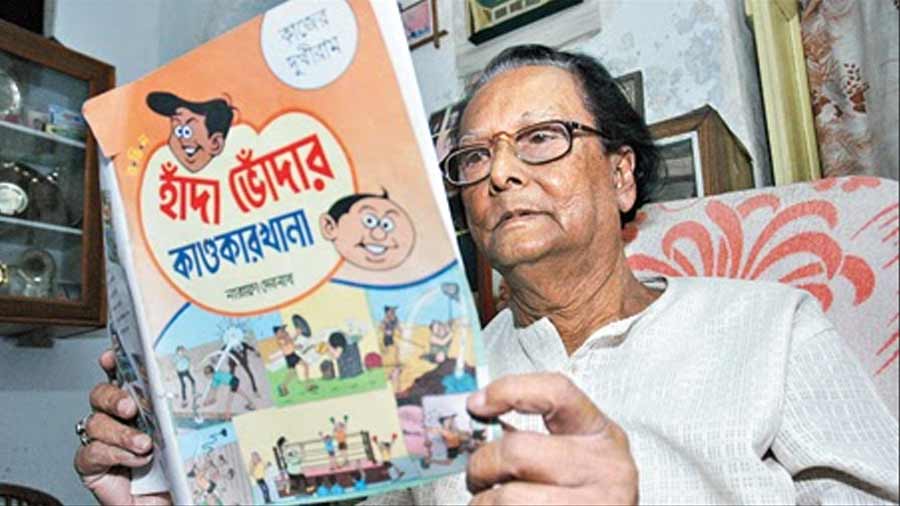

Mukherjee looks on as Debnath signs his book Courtesy: Hritam Mukherjee

A once in a lifetime meeting

In 2018, when I came across an opportunity of interviewing him for a magazine I was then associated with, I hesitated from instantly agreeing. Although I knew it was one of those rare reckonings that comes once a lifetime, I was positively intimidated to visit the visionary whose nib had illustrated a considerable part of my boyhood. The day I met him for the interview at his Howrah residence, was coincidentally also an autumn afternoon, a Sunday in October.

His personality was a cumulative reflection of decades of delight and joy that readers have absorbed from his art. During the three hours that I spent interviewing him, he was warm, convivial and charmingly witty. A stellar storyteller, he narrated incidents from his own life as evocatively as he sketched his characters, his words painting equally bright pictures as his brush has. My initial apprehension ebbed away, and the interview transformed into a candid conversation between a young boy and a man of his grandfather’s age.

Debnath at work Courtesy: Hritam Mukherjee

As a child, I was averse to many mainstream comics of the day due to their tendency of displaying violence in the garb of valour. Upon asking, he opined that comics should primarily be about laughs and humour. He added that comics is a genre that easily captures the fancy of kids, and excessive bloodshed and violence in it can have an adverse impact on their psychological development. I felt my own thoughts echoing in his answers.

As enjoyable as it was, talking to him provided me with an insider’s perspective to the-then-prevalent Bengali comics industry. He recalled incidents of his early days very poignantly, when comics as an artform was denied the appreciation that it enjoys today. He reminisced about his struggles, and reiterated incidents of favouritism and politics that had demotivated him in his formative years.

Shelves of Debnath’s study filled with his awards and trophies Courtesy: Hritam Mukherjee

After 65 years of a glorious art career, the walls of his study room were lined with trophies and mementos. But for him, the shiniest award and the most bejewelled achievement remained his readers’ appreciation towards his body of work.

The end of a chapter

In 2021, Debnath was awarded the Padma Shri, the fourth-highest civilian award in India. He was hospitalised when the award reached him this year, he accepted it in his hospital cabin four days before he breathed his last.

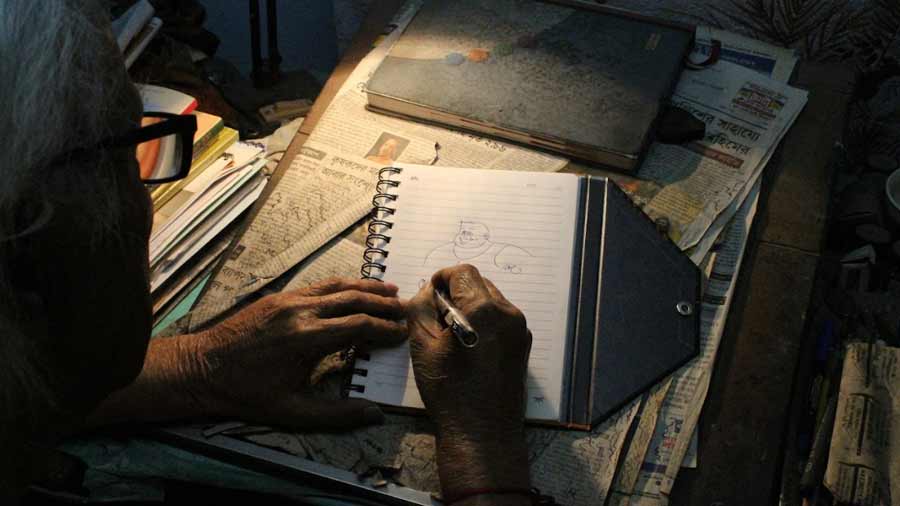

Debnath drawing a bust of his famous creation, Bantul the Great Courtesy: Hritam Mukherjee

Many of his fans took to Facebook to draw a poetic analogy, about how his life waited for this apex recognition before it silently flitted away.

But while this analogy is going viral on various social media platforms, I am reminded of his words from the interview, somehow very counterintuitive today: “Even when I’m not there, all the characters I’ve created will stay. And I’ll live on through them.”

If Bengali comics is a book in progress, then Debnath’s demise is definitely the end of a significant chapter. In his life, and after his death, he leaves behind a rich artistic legacy. But if we do not introduce our later generations to his comics, we will be gutting it with our own bare hands. If Debnath’s memory is to be truly honoured, it is imperative that interest towards his comics be cultivated among more and more kids.

On any given autumn afternoon, that book on the shelf of my school library will welcome its new readers with wide open arms.