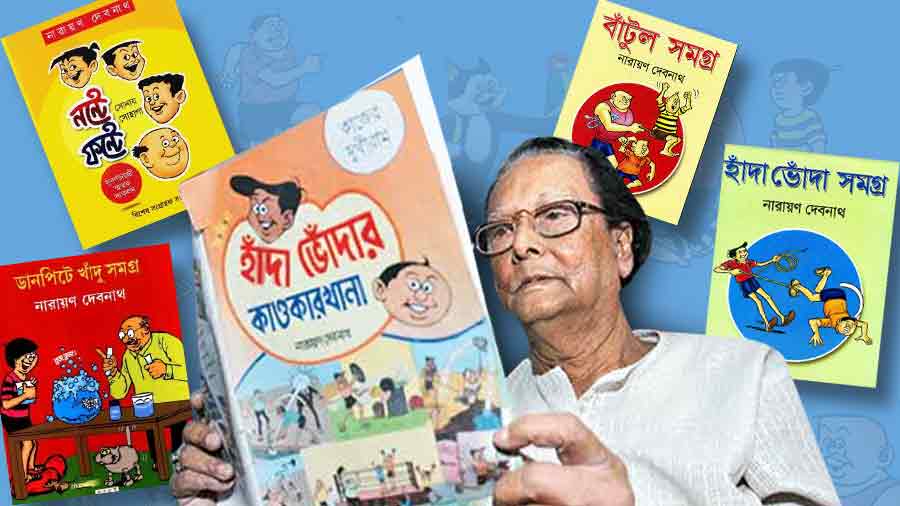

Walk past a streetside magazine vendor in Kolkata and somewhere in the midst of the glitz and glam of celebrity magazines and luxury tourist destinations, you are sure to spot a thin collection of comics, conspicuous by their very simplicity (some of them even being in black and white!). In this, they are not very unlike the modest, quiet, unassuming man who created them, and in so doing, revolutionised the sphere of Bengali comics.

In an effort to understand one of Bengal’s pioneering comic artists a little better, My Kolkata decided to catch up with famous Indian cartoonist Debasish Deb, who took us on a journey into the world of illustrations, comic characters and the man who created them all.

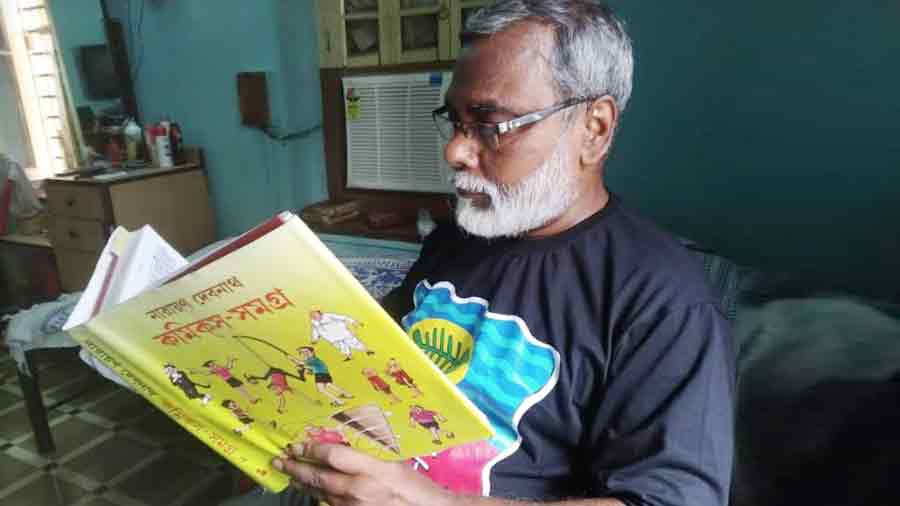

Cartoonist Debasish Deb, immersed in a Narayan Debnath book

Buy Debasish Deb’s Aankay lekhay chaar doshok here.

“In one of the interviews that I conducted with him, he admitted that before he became a comic artist, the only comic book he was familiar with was the Tarzan comics!” recollects Deb, as he tells us how, being a well-known illustrator of the times, Narayan Debnath never had any aspirations of becoming a comic artist. Debnath’s foray into comics was because of an increasing demand for comic strips. Despite not being very well-informed about the genre, the then illustrator decided to take up the challenge. Thus appeared the very first comic strip of Hnada-Bhnoda in the 1962 June-July edition of Shuktara magazine.

The rest, as they say, is history.

“Hnada-Bhnoda was an instant hit. Here was a pair of characters, very much like the infamous Laurel-Hardy duo, who got into all sorts of trouble and very often paid the price for it. It was light-hearted slapstick humour and people loved it,” observed Deb. Featuring two boys, one lanky (Hnada) and the other bulky (Bhnoda), the comic strips were initially sketched and inked by Debnath himself until Shuktara decided to start printing them in grayscale.

Hnada, a tall, thin chap with a penchant for creating mischief, was often seen as constantly devising ways to land others, especially Bhnoda, into trouble. However, by the time most of these stories ended, the former was seen in flight, as a last-ditch effort to escape punishment, unless of course that punishment had already caught up with him, in which case, the reader had the delight of watching him endure (not very gracefully, one might add), the many blows that landed on his back. Complete with a bad-tempered uncle who often ended up being collateral damage for their many mischievous plots, and a few other scattered tertiary characters, the comic strip was a delight for both children and adults.

Owing to the immense success of Hnada-Bhnoda, Narayan Debnath was asked to create another comic character, leading to the inception of another character, Bantul the Great. Multiple accounts state that Bantul was inspired by Debnath’s friend Manohar Aich – famous bodybuilder and the second Indian ever to win a Mr. Universe Title. Bantul, in many ways, also bore resemblance to Desperate Dan, a regular character in the then popular British comic magazine for children called The Dandy. When the comic strip was first started, Bantul lacked the superpowers he later became famous for. He was strong, almost Herculean in his physique, but with his trademark pink vest and black shorts, he was also your average run-of-the-mill next door neighbour – someone you could seek out for help every now and then. Bantul’s growth into the invincible protagonist he eventually became, started with the Indo-Pakistan war of 1965 and continued through the Bangladesh War of Liberation which took place in 1971.

If you flip through a Bantul comic strip, you will often find him single-handedly stopping tanks and diffusing bombs. Bullets bounced off his chest and he was sought out by army generals who required his help to stop an attack. “Bantul got involved in the war. He reflected the people’s sentiments and that was the time when the character really flourished,” notes Debasish Deb as he goes on to talk about the progress of the character from being simply strong to becoming someone akin to superman. Despite all that however, the character retained his simplicity. Perhaps it was because of his enormous appetite or perhaps it was because of his uncomplicated affection for his two companions (brilliant pranksters in their own right), Bantul continued to remain a favourite with audiences both young and old.

And then came Nonte-Phonte.

The prime setting for Nonte-Phonte was in the boarding school of a semi-rural town of Bengal. The only authority figure here was a booming superintendent of the hostel, who, like the uncle in Hnada Bhnoda, often bore the brunt of Nonte and Phonte’s numerous pranks.

While at first glance it may seem like they are twins, Nonte and Phonte, despite their obvious similarities, are simply friends who co-exist in the hostel. Another memorable character from this comic strip is Keltu da – a 20-something-year-old who also happens to be living in the hostel and is a senior to the two boys. This tall, wafer-thin fellow is considerably older than the other teenagers around him, possibly because he has failed in class multiple times. While he might occasionally conspire with Nonte-Phonte, most of the boys’ antics are aimed at this senior as payback for all the times that he devises ways to bully them or get them into trouble with the authorities.

“One thing that unites these characters is food. Almost all of them have a mashi (aunt) or a thakur (cook) who can be trusted to rustle up delicacies that are favourites across Bengali households,” says Deb as he talks about how these characters became a reflection of the society and the life of those times. For example, having characters who are all big foodies, is integral to establishing a connect with the young Bengali reader who perhaps shares these cravings and therefore can sympathise with Nonte-Phonte when Keltu da steals a chop from them or relate to Bantul’s appetite when he stuffs his mouth with freshly made rosogolla or completely understand why Hnada-Bhnoda need to devour that big bowl of payesh all at once.

Apart from these three however, there is a whole other crop of characters that the comic artist is credited with. “He also created the characters of Shutki and Mutki, which revolved around two girls and were very similar to Hnada-Bhnoda. However, it was not as well received by the audiences back in the day who perhaps could not quite envision girls being portrayed as foolish and mischievous,” considers Deb. He goes on to name some of the other characters that Narayan Debnath came up with, key among them being Bahadur Beral (very reminiscent of Disney and its plethora of walking, talking animals), Petukmaster Batuklal and “Daanpite Khadu ar tar Chemical Dadu” – all of them deserving equal praise in their own right, but somehow unable to surpass the fame of those three iconic comic strips.

According to Debasish Deb however, somewhere in the midst of these comic characters, Bengal lost out on a very powerful illustrator, “As the pressure of creating new comics increased, illustrations naturally took a back seat. However, Narayan Babu’s illustrations were striking because of their meticulous detailing and originality. One could see that these were well researched and authentic illustrations which was a feat in those days given the absence of the internet.”

Be it illustrations or comics, it is clear that Narayan Debnath is a stalwart in the world of Bengali literature. To that end, if you browse through the bookshelf at any Bengali household, you are sure to chance upon at least one old, battered copy of a Narayan Debnath comic, as revered and indispensable as Vidyasagar’s Bornoporichoy and Tagore’s Sahaj Path. One might say that together, they form the holy trinity of childhood reading for Bengalis.

Buy the comics here.