One has turned his lens on akharas and the dying art of kushti; the other focuses on the lost beauties of nature. French multidisciplinary artist Helene Guetary and Indian photographer Jayesh Sharma collaborated to create a photography exhibition, Endangered Spaces (exhibited at the Indian Museum recently), which examines how globalisation is leading to the decay of the modern world. My Kolkata spoke to the duo about working across borders and languages.

My Kolkata: Can you take us through your respective projects?

Helene: During the pandemic, I had an urge to visually depict how vulnerable we are as a society. People take the beauty of places like Venice, the Sunderbans and the Caribbean for granted. But, in reality, those environments are crumbling. I wanted to ensure that people cherish these gifts that we have received. Thus, I started photographing a ‘Red Phantom’ in places that need attention. This character represents resistance and passion for these vulnerable spots. I started looking for things that inspired me, and began staging the Phantom there.

Jayesh: I am from Varanasi, where kushti is one of the oldest practices. Its connection with the land, through mud, is what attracts me. Since the last seven years, I have been exploring places that practise kushti, and why it is considered to be among the purest forms of art. It isn’t just a sport, but a way of life. It benefits both physical and mental health, and pehelwans see it as meditative and medicinal. A pehelwan isn’t a quintessential fighter or gym-lover, but they represent the peak of the Indian body. An akhara is like a gurukul, but unfortunately, very few are left in India now, with COVID making the situation even worse. Akharas were mostly patronised by royalty and zamindars, but the government never took over from them. Moreover, these akharas aren’t easily accessible, and are very reserved about showing themselves. My project is about understanding these cultural practices, which are dying in a world regulated by the Graeco Romans. I started out taking pictures at Swaminath Akhara, which is one of the oldest in Varanasi, and then started sitting on the mud with the wrestlers and learning their ways. Over the years, I have found akharas in Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Varanasi that are over 500 years old. Their rituals and soil are both considered holy, and I have tried to explore what has allowed these akharas to sustain till date.

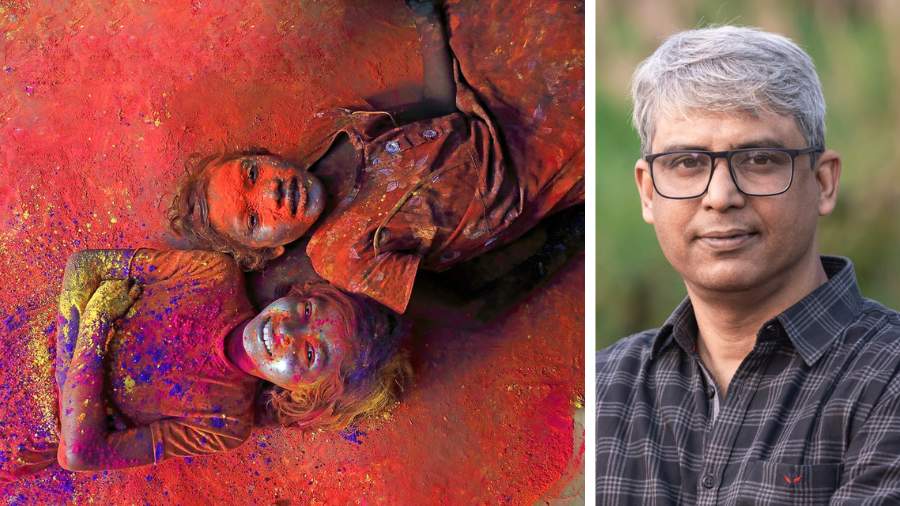

Frames from Jayesh’s adventures in akharas

How did you decide to blend your projects into this exhibition?

Helene: I had come to India last year, looking for inspiration for my Zeitgeist project. That’s how we met — at the India Art Fair in Delhi. There was a parity in our vision, as both our projects were a call to attention. While mine was for a dying environment, his was for a dying culture. Moreover, neither of us wanted to show things as wasted, but things that are still very beautiful. We wanted to show life, and warn people of losing it if they weren’t careful. There was an instant connection, because we both spoke about our work in the same way.

Images from Helene’s Zeitgeist project

Jayesh: I was immediately attracted to how Helene saw environmental degeneration through the Phantom.

Helene: Something clicked when we met. This is even more interesting because we are both very different. This collaboration is between a French woman and an Indian man, who have different subject matters and different ways of expression, but are interested in the same thing: the precious resources that humanity is losing.

Given your different perspectives, what was it like to work together?

Jayesh: When we started discussing a collaboration, I couldn’t stop thinking about how the Phantom is a spirit. Every akhara has the invisible presence of Lord Hanuman, and Helene’s Phantom felt like a similar energy — driving the wrestler to continue fighting for the existence of this 2,500-year-old practice. I believe that there is a spiritual reason that it continues to exist, irrespective of how rare it has become. I wanted to create an abstract metaphor of these wrestlers through Helene’s Phantom.

Helene: Honestly, I was surprised that we worked so well together visually. Even if you explore our exhibition, the audience will have a very interesting experience while going from my work onto his, and vice versa. During this collaboration, both of us maintained our own identity and taste, and hoped to get the message across as intended. It is quite incredible that two different artists have the desire to say the same thing. Our distinct strengths add to the exhibition, since Jayesh has a localised view, while I bring a globalised view.

Jayesh: We had a common dream of preservation. The culmination of our vision was a video installation, where we shot an akhara in Varanasi, and connected the Phantom with kushti. Helene has worked in cinema for a long time, but for me, this was a new learning experience. It really worked, because we maintained our respective visions from our countries and cultures, while trying to say the same thing.

Helene: When I looked at his depictions of kushti, it felt like the photos came alive. They were so full of strength and life, without any decay. Both of us aspired to show endangered things by highlighting their beauty, not their vulnerability.

Jayesh: Our vision was to not just emphasise on one single picture. We wanted the exhibition to feel like a film.

Helene: When you pile single images one after the other, it becomes a story. This exhibition has a narrative, where you can find the common while moving through the photos. While conceptualising it, I felt things would be difficult to arrange, but the dots connected organically.

How has this collaboration changed you as photographers?

Helene: I started filmmaking during the pandemic, but went back to photography because I could blend narration, storytelling, images and painting together. It gave me the freedom to do this crazy project all by myself, with barely any resources. I love directing a crew, but for many years, I felt like I was just fighting for finances. I love this autonomy. When I went to rural India, I collaborated with whoever was around. I would tell people about the things I wanted to call attention to, and everyone would take me to their favourite places. The Phantom created a link between me and people. During the pandemic, all the cultural spaces in France had shut to the public, but they invited me into their empty museums and theatres. In fact, a fisherman who drove us In Caribbean, asked if he could volunteer as our Phantom!

Jayesh: Freedom is very important when you work on a serious project like this. I can’t go to an akhara with 2-3 people. Even for our video installation, we had started with still images of the wrestlers, and midway got the idea to shoot a video to better capture the exercises. When the stills of the Phantom connected with the movement of wrestlers, it created a unique aesthetic. The energy of the surroundings, poured into the Phantom.

Helene: I now see myself less as a photographer, and more as an artist who is using photography. For me, photography is all about magical realism, where I show something that isn’t there, as if it was there. It helps me make metaphors a reality.

Jayesh: Photography has various categories, and it takes a long time to understand where you belong. Your perception changes as you collect more data. Projects like these also empower you with more knowledge about cultures and nature. I started out doing street photography, but now, because of kushti, I want to take pictures through the lens of a researcher.

Helene, you mentioned that this project took you around India. What was that like?

Helene:I had always wanted to travel through India to explore its diversity. The same country has deserts, islands, and grand architecture, all worth preserving! I enjoyed photographing the backwaters of Kerala and the forts of Rajasthan. I arrived in Kolkata for the first time last January 2023, hoping to capture its lost palaces, and explore the mangroves of the Sunderbans. I immediately fell in love with this city, and it strangely made me feel at home. Maybe because of its artistic similarity to Paris (chuckles). I feel that we Westerners don’t have the right idea about Kolkata — and only picture its poverty. But it also has so much vibrance and culture, especially in its architecture. I got to visit Basu Bati in Bagbazar, and it was so magical, given how the structure was crumbling but still full of life. I also got to visit the Sunderbans, where it felt like the water was so expansive it would envelop me.

Helene gushed over the structure of Bagbazar’s Basu Bati, which she captured in her project

Is there another joint project on the cards?

Helene: For now, we are focussed on bringing this exhibition to Mumbai next month. We had a great time working together in Varanasi and would love to collaborate on more projects, but geographically it isn’t easy to coordinate. This exhibition is the result of many years of work, with a lot of travel, research and networking. Then again, who knows, we might pick a project in another country.