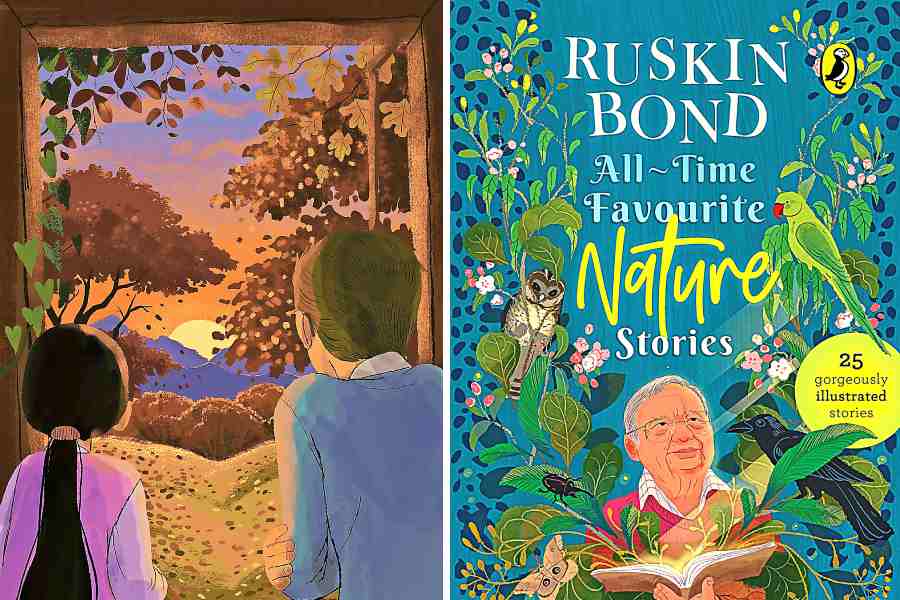

On the occasion of the 89th birthday of author Ruskin Bond, a favourite of readers of all ages, especially children, has come the release of All-Time Favourite Nature Stories from publisher Puffin India.

The book is a celebration of Bond’s love for nature. It has 25 short stories curated by Bond himself and illustrations to go with them. The publisher describes it thus: “Part fiction and part real, and a continuation of the All-Time Favourite series by him.... The book is also a homage to his childhood spent in the hills of Kasauli, Shimla, Dehra, and Landour.”

Bond writes: “The trees of my boyhood in the valley gave me many stories. The mango groves, the guava orchard, the lichees of Dehra. The peepal, with its slender-waisted leaves, fluttering in the slightest breeze, and the mischievous Pret who lived in its branches, coming out at night to frighten unwary travellers.... So I am lucky to be up here on this mountain, where the wind still hums in the deodars, the horse-chestnuts fall in the autumn and the flycatchers flit among the ancient oaks.”

Each story is replete with a different sensorial experience: rustling leaves, still forests, burbling streams, chirping birds, picturesque landscapes and so on. It is, in essence, about Bond’s love for nature. Here is an extract from All-Time Favourite Nature Stories.

EXCERPT The Window

I came in the spring and took the room on the roof. It was a long, low building which housed several families; the roof was flat, except for my room and a chimney. I don’t know whose room owned the chimney, but my room owned the roof. And from the window of my room, I owned the world.

But only from the window.

The banyan tree, just opposite, was mine, and its inhabitants were my subjects. They were two squirrels, a few mynah, a crow and at night, a pair of flying foxes. The squirrels were busy in the afternoons, the birds in the mornings and evenings, and the foxes at night. I wasn’t very busy that year — not as busy as the inhabitants of the banyan tree.

There was also a mango tree, but that came later, in the summer, when I met Koki and the mangoes were ripe.

At first, I was lonely in my room. But then I discovered the power of my window. I looked out on the banyan tree, on the garden, on the broad path that ran beside the building, and out over the roofs of other houses, over roads and fields, as far as the horizon. The path was not particularly busy, but it was full of variety — an ayah pushing a baby in a pram; the postman, an event in himself; the fruit and toy sellers, calling their wares in high-pitched familiar cries; the rent collector; a posse of cyclists; a long chain of schoolgirls; a lame beggar... all passed my way, the way of my window.

In the early summer, a tonga came rattling and jingling down the path and stopped in front of the house. A girl and an elderly lady climbed down, and a servant unloaded their baggage. They went into the house and the tonga moved off, the horse snorting a little.

The next morning, the girl looked up from the garden and saw me at my window.

She had long, black hair that fell to her waist, tied with a single red ribbon. Her eyes were black like her hair and just as shiny. She must have been about ten or eleven years old.

‘Hello,’ I said with a friendly smile.

She looked suspiciously at me. ‘Who are you?’ she said.

‘I’m a ghost.’

She laughed, and her laugh had a gay, mocking quality. ‘You look like one!’

I didn’t think her remark was particularly flattering, but I had asked for it. I stopped smiling anyway. Most children don’t like adults smiling at them all the time.

‘What have you got up there?’ she asked. ‘Magic,’ I said.

She laughed again, but this time without mockery.

‘I don’t believe you,’ she said.

‘Why don’t you come up and see for yourself?’ She hesitated a little but came around to the steps and began climbing them, slowly and cautiously. And when she entered the room, she brought a magic of her own.

‘Where’s your magic?’ she asked, looking me in the eye.

‘Come here,’ I said, and I took her to the window and showed her the world.

She said nothing but stared out of the window, first uncomprehendingly and then with increasing interest. And after some time, she turned around and smiled at me, and we became friends.

I only knew her name was Koki and that she had come to the hills with her aunt for the summer; I didn’t need to know anything else about her, and she didn’t need to know anything about me except that I wasn’t really a ghost — at least not the frightening kind. She came up my steps nearly every day and joined me at the window. There was a lot of excitement to be had in our world, especially when the rains broke.

At the first rumblings, women would rush outside to retrieve the washing from the clothes line and if there was a breeze, to chase a few garments across the compound. When the rains came, they came with a vengeance, making a bog of the garden and a river of the path. A cyclist would come riding furiously down the path, an elderly gentleman would be having difficulty with an umbrella and naked children would be frisking about in the rain. Sometimes Koki would run out to the roof and shout and dance in the rain.

And the rain would come through the open door and window of the room, flooding the floor and making an island of the bed.

But the window was more fun than anything else. It gave us the power of detachment: we were deeply interested in the life around us, but not involved in it.

‘It is like a cinema,’ said Koki. ‘The window is the screen and the world is the picture.’

Ruskin Bond’s picture: B. Halder

Illustration and book cover:Courtesy Puffin India