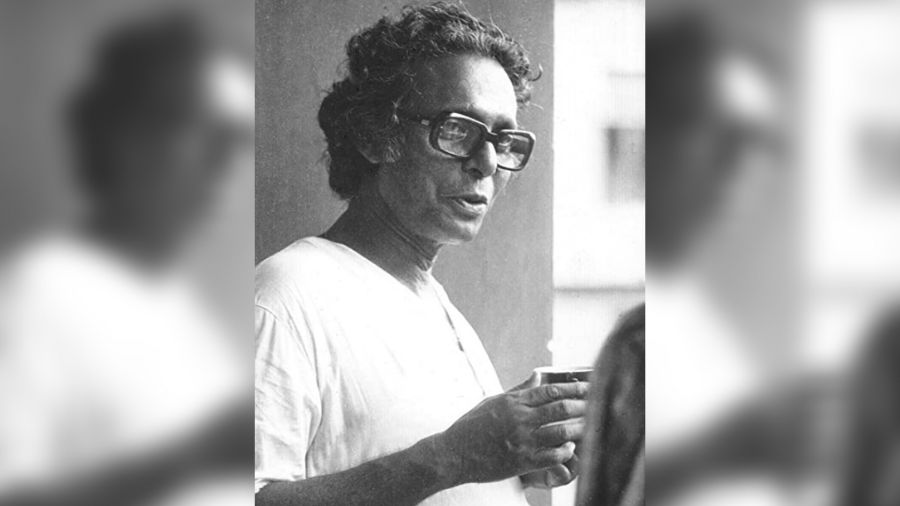

Growing up in a house that served as the production office for his father’s films, Kunal Sen — son of filmmaker Mrinal Sen — often shared his study and adda space with film meetings. In Kolkata recently for the release of his debut book Bondhu, which is a memoir of the celebrated filmmaker, Kunal Sen made time for a candid chat with My Kolkata about his visits to the sets and the editing room, regular dose of morning-show Hollywood fare and more.

Edited excerpts from the conversation follow.

My Kolkata: Was cinema a large part of your growing up?

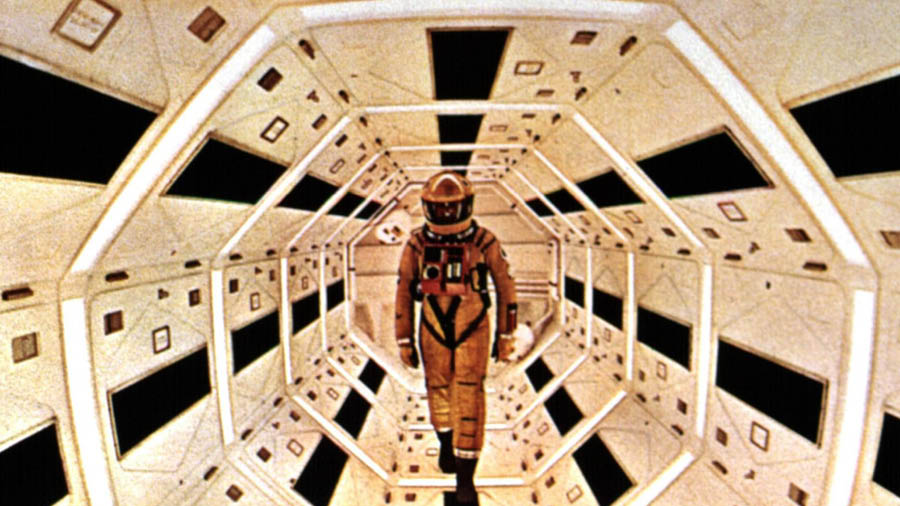

Kunal Sen: Yes, I loved watching films. However, until I was 15 or 16, my interest revolved around Hollywood films. Every Sunday, most theatres would have a morning show. I would carefully scan the newspaper in the morning to pick an English film that caught my attention and go and watch it. One of my favourites from when I was a little older (15 or 16 years) was Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. It still remains a favourite. However, starting around the age of 15, I started to develop a taste for better cinema. We used to get invitations from many local film clubs, and I started going. I was never particularly attracted to commercial Bengali or Hindi cinema, though I used to watch them from time to time.

Stanley Kubrick’s ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ remains one of Kunal Sen’s favourite films IMDB

Growing up in that household, I was also getting exposed to the process of filmmaking. Unlike my school friend Sandip Ray, I never had any planned desire to be a filmmaker. Therefore, unlike him, I was not part of my father’s film crew. I would attend a few shoots and sometimes be in the editing room, but never regularly. My father’s film productions were also very lean, and he discouraged too many visitors as that would have affected their mobility. Even though I was not a regular, since our house was also their production office — which was also the room where I studied or met my friends — I became intimately familiar with the process. If I’d decided to take up that profession, I think that intimate familiarity would have helped.

Did you grow up around the sets or visit the sets a lot? What is your fondest memory from those visits?

Sometimes. I was not a constant companion and most of his shootings were done outdoors where too many people created problems. So, he always wanted to go in small groups that could fit in a car. If it was something around my home during my college days, I’d often visit. I was not directly involved except in the editing, maybe to some extent. But it wasn’t like with Sandip, who was one year senior to me in school (Patha Bhavan). We were among the first 18 students at Patha Bhavan, which was a school created by some of my father’s friends. When it came to Sandip, we always knew and the school accepted that whenever his father (Satyajit Ray) was making a film, whether shooting or post-production, Sandip would hundred per cent be there with him. So, every year he would be off for two, three or four months because he was involved. I never had that desire to become a filmmaker.

A post by Kunal Sen remembering his father on what would have been the filmmaker's 98th birthday Courtesy Kunal Sen

Any memories of Mrinal Sen, the director, on set?

He was a very different person while shooting. In a private setting, he was a jovial person with a significant sense of humour. However, during his shooting, he became very tense and would snap very easily. That was in part because of the fact that in most of his films post Bhuvan Some, he was innovating a lot. He was deviating from the script a lot. And when you are trying to think on your feet and innovating, you become more tense about everything. So he was always very tense during shooting, his crew knew that. He screamed at everyone, but I have not seen that having any lasting impact on them because they knew that this is shooting time.

Mrinal Sen in front of the family radio at home Courtesy Kunal Sen

There is one incident that I remember. I was on set during the shoot of this film Mrigaya near Massanjore and one of his assistant directors Soumendranath was asked to play a small role where he was supposed to read the king’s decree. He had a piece of paper that he had to read from and since he had the piece of paper with the dialogues written, no one gave him a chance to practise it or memorise it. The problem was, the costume included a pair of glasses with incredibly thick lenses. So, he could barely see the paper, forget about what’s written on it. He was making mistakes, my father was screaming, but he could never tell him that ‘Mrinal-da I can’t read what is there’. I mean, he just gulped it down.

For me, the most tense event in his shooting days was during the time I was not married to Nisha but we were going out. He asked Nisha to play a tiny role in Ekdin Pratidin. She was to play a nurse and would be walking towards the camera. There was a line on the floor and she had to stop at the line because that’s where the focus point was, and say her one line. She agreed but did not know how he behaved on set. So for once, on a rare occasion, my mother said she would go to the studio because she did not want to lose a potential daughter-in-law. She was there to mediate, and I was very tense.

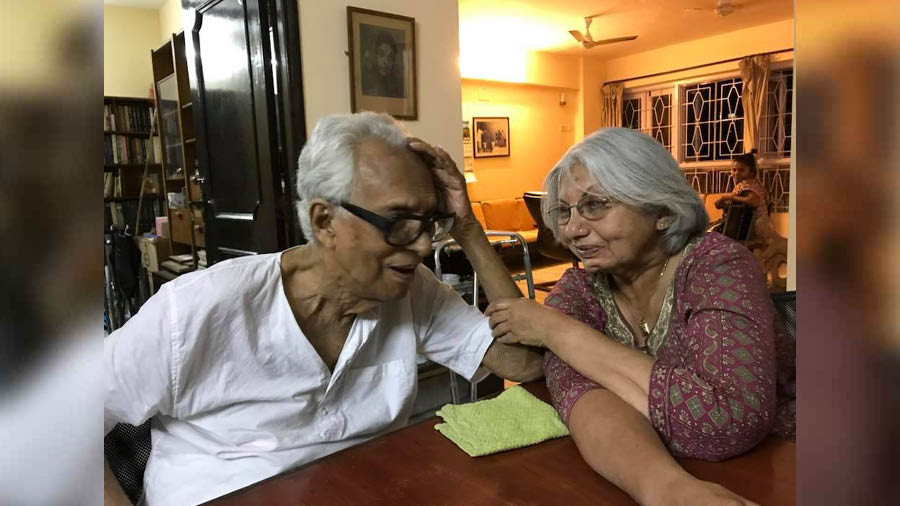

Mrinal Sen with his daughter-in-law, Kunal Sen's wife Nisha Courtesy Kunal Sen

During the shot, Nisha looked at the line below and started to say her line. He said, “No no no, you can’t look down!” To which she responded, “How will I know where the line is if I don’t look down,” and she started laughing. I thought, “This is dangerous! You are making a mistake!” They put a few chappals out there so she did not have to look down and could feel it instead and they moved and tilted the camera up so that the chappals were not visible. She kicked the chappals all over the place and again was one step forward. My father did not say anything. Next, one of the assistants was lying on the ground so he could tackle her legs and the camera was further tilted up so his head did not come in the shot. That finally worked, and was still cool. The next shot was with this an older person who was playing an extra role and he was supposed to sort of faint on hearing the news of the death of a patient. Nisha was supposed to grab him and he was supposed to rest. This man was too careful and could not lean on another woman, so he would come close and freeze. And he was at the receiving end of my father’s pent-up frustration that had been building up all this time. That’s probably one of my most memorable moments.

How would you define your father as a filmmaker?

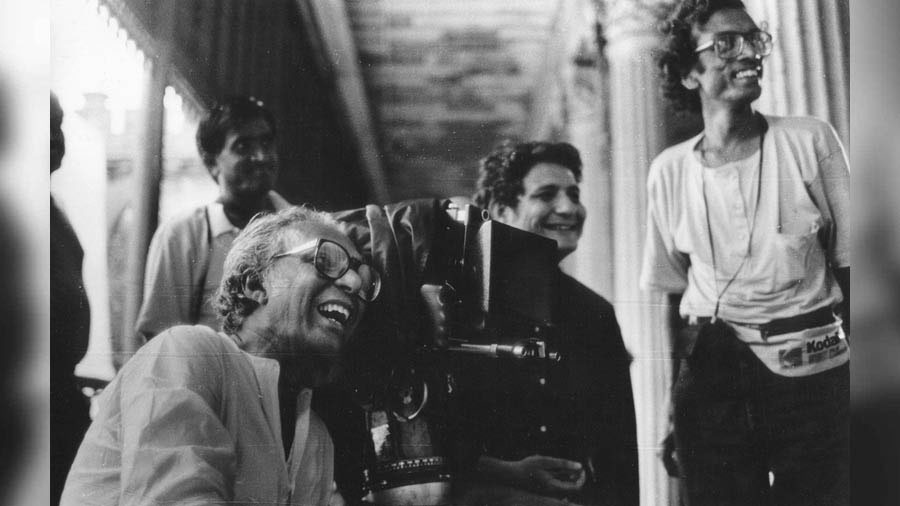

A photo of Mrinal Sen on set, shared by Kunal Sen on the eve of the director's 91st birth nniversary Courtesy Kunal Sen

That is a question I generally try to avoid. It is hard to be objective about someone so close to you. Moreover, people are not going to give me the benefit of doubt. If I have to say something, his distinction lies in his uncompromising desire to experiment, to never settle down into a tested pattern. Most artists, of all kinds, fall into this trap. They try many different things, and one day they discover that their audience likes a certain style. Once that happens, they more or less stick to that. If you watch my father’s trajectory, he never spent more than two or three films before moving in a different direction, both in terms of form and content. This courage is somewhat rare. The other quality he had was his responsiveness to his present time. He was also a restless artist, which made his films more energetic but also imparted some rough edges.

What are your five favourite Mrinal Sen films?

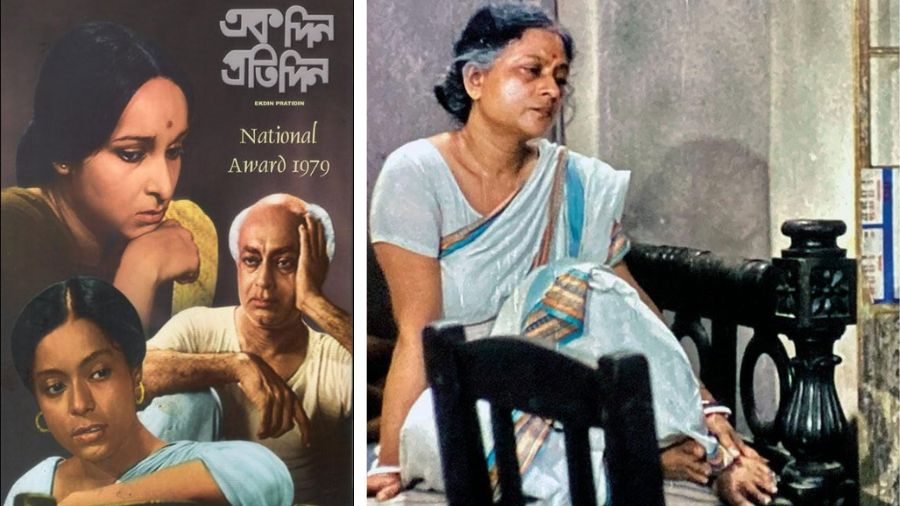

I like different films for entirely different reasons. I still have a very soft corner for Bhuvan Shome for its freshness, for when it was made and how it looked. I saw it when my own awareness was evolving so it felt very close to my taste and my liking. I like Padatik a lot for its content and the tone of critiquing something. It’s a film with a debate that you often don’t find very well done in many films. I like Ekdin Pratidin and Kharij, combining those two for the story and the way it is told. I am very fond of Khandhar because of its depth. There is one more film that no one has seen here — Chalchitra. I find it to be one of his modern films in its structure and style.

A scene from ‘Chalchitra’ YouTube

That film (Chalchitra) had a bad start. Right after the film was completed, it had to go to an international film festival. I think it was Venice. They didn’t like the print that was sent so they asked the negative to be sent to them and they would make a print. And normally, when you send out your negative, you make a dupe or a duplicate. Either they didn’t have the money or the time to do so. The film was sent as it is, the negative. When the negative came back, it was lost in the Calcutta Customs. The negative was lost and the film never got released. But that one print survived somewhere in the world and it was shown recently at Berlinale (Berlin International Film Festival).

What about each of these films makes them closer to you or more special than the others?

They are distinctive to me for different reasons. Bhuvan Shome surprised me with its freshness. I first saw it when I was just 15, and its spirit matched the youthful rebellion we all harboured at that time. Padatik is a rare film because it is a debate. It presented an argument, and a very vital one, for that time in history. I have not seen too many films that present an argument so effectively. Ekdin Pratidin and Kharij were both such merciless dissections of our middle-class society. They are also very tightly crafted films. Khandhar is unique in its depth of capturing the cruel loneliness of its characters and the merging of the physical ruins with the two characters that live there. It is probably his most poetic film, where it is hard to define the film in a sentence. Chalchitra is a very modern film structurally. I don’t think it can be a popular film, especially in India, since we like wholesome stories and raw emotions. This film moves away completely from such expectations. I can’t think of too many films in India that risked telling a story, or lack thereof, with such style and detachment.

The poster of ‘Ekdin Pratidin’ and (right) a scene from the movie IMDB

Do you remember watching films with your father? What were some of his favourite films?

The only time we watched films together were either his own films, or other Indian films when we were invited, or at film festivals. We rarely went to film society screenings together. A few times, we attended film festivals together. The first was in 1972 while attending a couple of festivals in Manheim, Germany, and Neon, Switzerland. He was invited there as a jury member, and this was the first time my mother and I accompanied him. During these weeks, we watched hundreds of films together. I was just out of high school, so it was a bit awkward to watch sexually explicit films sitting next to my parents, but we quickly got used to it. Later, in 1981, we attended the International film festival in Delhi, and watched many films together. There were a number of Latin American films, a film by Fassbinder, another by Joris Evans, which left an impression, but the names and details are lost.

Father and son at the Cannes Film Festival, 2010 Courtesy Kunal Sen

I cannot recall if there were any films there that we both loved. There must have been, but I can no longer remember. He had many favourite films he talked about, and I watched them whenever possible. Films did not come by easily when we were growing up. There was no internet, on-demand viewing, or even video libraries. The only way to watch a film was to wait for the film to be shown at a film festival or by a film club. Very often, it was a chance of a lifetime, and if you missed it, you missed it forever. Most of the films he talked about were from Europe, from all the expected filmmakers.

Tell us about Mrinal Sen’s process of preparing for a film.

If the story is something that required background research, he would do a lot of reading for that. If it was a fictional story, he would often read stories or novels by the same writer because he changed the story from the printed text a lot. He took a central line and it evolved around that. So that was one part of the preparation.

Shabana Azmi and Mrinal Sen during the shoot of ‘Khandhar’ TT Archives

The second part was choosing the cast. There was a period when he exclusively used newcomers. He didn’t want known faces. So, from Bhuvan Some onwards, for a while it was mostly new faces. When it comes to new faces, you don’t know their acting capabilities most of the time, so he relied on their attitude and their face, etc, and there is a risk to that. His other unit, his team members, changed less. I mean there was a lot of continuity, and some new people came in every time. Later on, as his stories became more complex, he relied more on established actors. And very often the actors determined other things. For example, for Khandhar, he wanted Naseer (Naseeruddin Shah) and Shabana (Azmi). Therefore, it had to be a Hindi film, even though the milieu was completely Bengali. So, his reliance on more established actors became very clear towards his later films where he went to the same set of actors that he trusted. And the trust was really necessary because he relied on them not just for acting but crafting their dialogue, creating the situations — it was more of a collaborative work than a prescribed work.

Rapid Fire

One Mrinal Sen movie that the younger generation must watch

Interview

Your least favourite Mrinal Sen film

Probably Ek Adhuri Kahani

Mrinal Sen’s favourite author

I can’t name one, but probably is Manik Bandyopadhyay

One thing you remember your father saying often?

Whenever his body temperature crossed even a 100, he would say “Mrityu samasanna!”