Paul Walsh landed in Kolkata on an early November morning in 2002. He remembers that journey vividly – he was booked on the Dutch airline KLM, aboard the old reliable Boeing 747, which was to travel from London to Amsterdam, and then stop at Delhi before Kolkata. He recalls that almost everyone disembarked at Delhi with only about ten people remaining behind to go to Kolkata. As the plane dipped through Bengal’s skies, he was struck by the view from his window seat – coconut trees, paddy fields, little ponds and acres of green. “It looked exotic… the way the tropics should look…”

From dusty Wales to dusty Kolkata

Growing up in Northwest England, on the Welsh-English border, prepared Paul (yes, he is Paul to us all, even Paul-da to a few!) in some ways for a life in Kolkata. If the wind happened to blow in a certain direction, the village would be cloaked in a layer of dust from the cement works and the women would complain about having to clean the windows. “It was nice but wasn’t exactly singing-from-the-hills kind of beautiful,” he says, wryly.

Paul was not entirely unfamiliar with Kolkata; he’d had occasion to visit the city once, before moving to India. And he’d also read Dominique Lapierre's City of Joy (which, he admits, wasn’t a great idea!). It was with curiosity that he slid into the car sent for him by the British Deputy High Commission, his liveried chauffeur assuring him that the large stadium they were gliding past in Salt Lake was not in fact Eden Gardens, that it was "the largest football stadium in the world". Paul, caught off guard by the epiphany that he had landed in a city crazy about football, wasn’t quite prepared for the sight of a bus bursting into flames before his eyes. “Somebody had been hit and the bus driver was being chased. Then, a brick landed on the road about 20 yards in front of us and people were streaming out onto the road…What the heck is happening here?!” he chortles.

The man at the wheel, quick on the uptake, put the car into reverse and went screaming back down the road. Paul thought about all the people who had been circumspect about him moving to Kolkata and couldn’t help but think, okay, where have I landed? But the car transported him swiftly to the gleaming haven of Taj Bengal, where he stayed for two weeks while his apartment was being painted, swimming in the pool every morning, settling into the easy life that so many associate with the city.

Paul Walsh on the Maidan with the Khelo Rugby team

The good life

Paul spent three-and-a-half-years at the British Deputy High Commission on Ho Chi Minh Sarani as deputy head of mission. He looks back now, almost amused, at the easy, pleasant life he left behind – a life which came with all the trappings of the people belonging to the top echelons of society. “You have your driver every morning to take you to an air-conditioned office, where you fiddle about with your emails. Every night you could go to a party or be invited to dinner. There are these club memberships as well… it’s an almost colonial lifestyle. That’s not the case everywhere you go but in Kolkata for sure…”

Paul remembers with particular fondness, the cook-cum-housekeeper attached to his luxurious Alipore apartment – a man called Anu who could organise absolutely anything, unflappable in the face of an impromptu party. Besides, Anu’s culinary repertoire was impressive. He had been discovered as a ball boy on the tennis courts of The Saturday Club in the 1950s. A Briton offered him a job in his house and there was no looking back. Over the years he worked in a series of expatriate homes, learning to make everything from Japanese tempura to a classic Christmas dinner.

But the good life is not why Paul Walsh chose Kolkata from the list of overseas postings he was handed in London. He wanted to avoid a large office populated by a hundred diplomats, and simply sink into the life there. “What I liked about the posting was that it was a very small office, which meant that you had quite a lot of responsibilities. You didn't have to do just one job. But the team I walked into when I went into the British Deputy High Commission in Kolkata, was very bright, very young. They didn’t need me; they could do the work, with one hand and blindfolded, because they were just so bright and smart. And I just kind of sat in the middle of all this talent and pulled a few strings.”

Paul Walsh with some of his team members in the British Deputy High Commission in Kolkata

Drop kick

But he did more than pull a few strings. He put together a team with his colleagues, John Hamilton and Gary Stilgoe, spontaneously coming up with the name Jungle Crows. He roped in a few other expats, some drivers and guards and they would all troop to the Maidan and throw a rugby ball around. He discovered that it was a city that loved sport. On his way to his first Mohun Bagan vs East Bengal match, someone tossed an East Bengal flag into his car. He picked a side then and stuck to it.

Paul Walsh (far right, front row) along with Gary Stilgoe (second from right, back row) and John Hamilton (third from right, back row) after a match

Paul began to leave office in time for practice and found himself grappling with the ropes of the game again, even though he’d played a bit of rugby growing up. Then he started to dig around for tournaments, arranged for jerseys and even managed a bit of sponsorship. They started playing 7-a-side tournaments at Calcutta Cricket and Football Club (CC&FC), which is when he discovered that rugby was being played here with teams like Kolkata Police, CC&FC and the NGO, Future Hope. Tim Grandage, the founder of Future Hope, had already been in the city for more than 15 years by then and would arrange for coaches to come in from the UK to train his kids. No wonder that the Future Hope team was almost unbeatable. Paul recounts a vague memory of these kids flying across a flooded field and wondering how they weren’t sinking into the mud. What struck him was how seriously they took the sport, playing with absolute conviction. “They came from the toughest backgrounds and they were really incredible. It was brilliant to watch them.”

Unbeknownst to him then, Paul had already launched into the next stage of his life. When it was time for him to leave for his next posting to New Zealand, he toyed with the idea of a career break. “The Foreign Service is encouraging of the concept until you actually ask for it, and then they weren't very cooperative about it. I suppose that's the only time I felt a bit let down by them,” he admits. Not that he wouldn’t recommend a career in foreign service to anybody. He himself intended to try his hand at something different and resume his life as a diplomat. After all, it had been a really good life.

He approached Tim Grandage, wanting to work with Future Hope for a few years, but Grandage didn’t take his proposal seriously, until Paul sent him a letter, emphasising his earnestness. There was no looking back after that.

“I suppose the thing that got me hooked was seeing the impact that our rugby club (as it had sort-of become) was beginning to have; it was a huge motivator for a group of young people, even though it was very disorganised."

Play rugby → teach kids rugby → teach more kids rugby → keep them in school

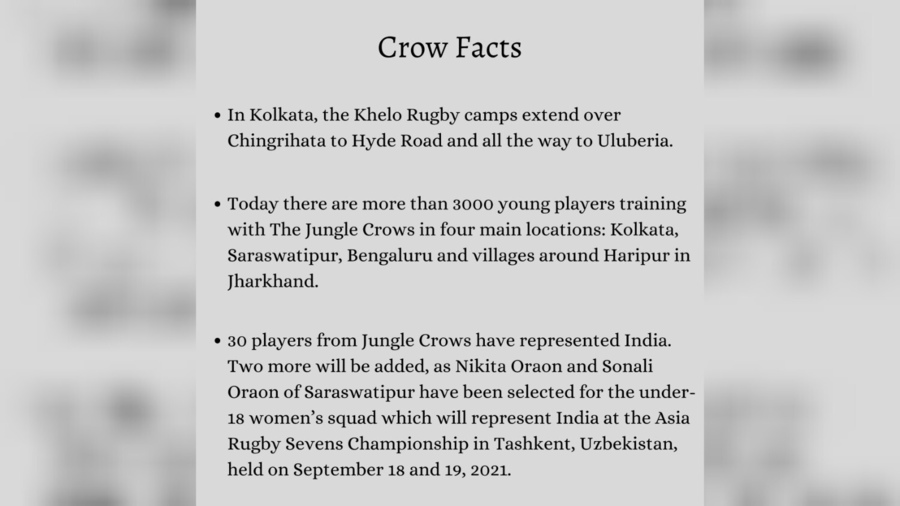

The Jungle Crows used the space on the Maidan allocated to the Rangers Club for seven years, before moving to their current plot which is across the road from the American Center. They started to draw more and more kids to the game. The Khelo Rugby programme, a sports-for-development project run by The Jungle Crows, started after an international NGO wrapped up operations in a Kolkata bustee and left a bunch of children stranded. The Crows swooped in to teach them to play rugby. “I didn’t think of it as social service. We started setting up rugby programmes in different areas, and it really took off,” explained Paul. The older kids would train the younger ones, bellowing “Khelo! Khelo!” to ensure the ball kept moving even after the players were tackled. And that’s what they named it.

Over the years Paul has buckled down to the task of helming not a rugby club but an NGO, one that aids the development of young people. He describes the steps succinctly – play rugby, teach kids rugby, teach even more kids rugby, and then help them go to school and college. In 2015, Paul-da became Sir Paul when he was awarded an MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire) – an award which is presented to someone for making a positive impact in their line of work.

https://junglecrows.net/khelo-rugby

Do they all make it, one wonders. All these hundreds of kids with hope and ambition emblazoned in their hearts in the shape of an egg-shaped ball. Paul is stoically philosophical about the human struggle he wakes up to face every morning. “No, of course they’re not all successful, they don’t even all get through school. They have to find a way of surviving, find a job, find a way of living. Once they work, they go in early and come back late and there’s no time to play a sport. They have struggles like everybody else. It’s life. And you can’t fix it for them, people have to fix themselves, have that ambition.”

Sweet, sour, bitter…

And yet he’s trying to fix whatever he can, even though he insists that what The Jungle Crows does has been done by lots of people around the world, that it’s not unique though many parts of it might be special. “But yeah, I mean it's, it’s amazing, I love it,” he says, his passion to live for something beyond himself evident in a flash. And suddenly it makes sense, that he’s been able to give up the old life for his current, less glamorous life, made even more torturous by the tedious process of having to apply for his annual visa. It’s clearly all worth it. Approaching the 19th winter since he first moved to the city, Paul confesses that his relationship with Kolkata has been “mainly sweet with some hints of sour and the odd, refreshing taste of bitter. But now, Kolkata to me means home.”

Video edited by Madhurai Banerjee.