Residents of Jodhpur Park will be familiar with the sight of Gour Das selling peyanji on his elevated kerbstone. For three decades, until lockdown 2020, the man has been a fixture at the corner, diagonally opposite Ashok Hospital, faithfully setting up his kerosene stand every afternoon. He used to be sold out in hours, before retiring to his dwelling inside one of the Jodhpur Park mini buses. He’s lived there for years, agreeing on a quid pro quo with the proprietor.

Gour Das and his ilk form the demographic who have possibly suffered the most since the onset of Covid-19. For Das, his wares went from being sought-after to being shunned, almost overnight. The 70-year-old sat for months on the kerb, surviving on alms from older Jodhpur Park residents who have partaken of his fries since they were children. A dependable young man, Ram, who was then posted at the Pay & Use Toilet next to the park, took it upon himself to share some of his own food with Das. “I’m a beggar these days,” said the peyanji-seller, in April 2021, the pride in his hollow eyes unmistakable through the hunger and desperation.

It was the lockdown induced by the second wave which was Das’s undoing. By then, narrowed veins and swollen feet had already made movement difficult, but an accidentally broken nail rendered him immobile with pain.

It is at this point that this bleak story of wretchedness takes a turn for hope.

Enter, Calcutta Rescue

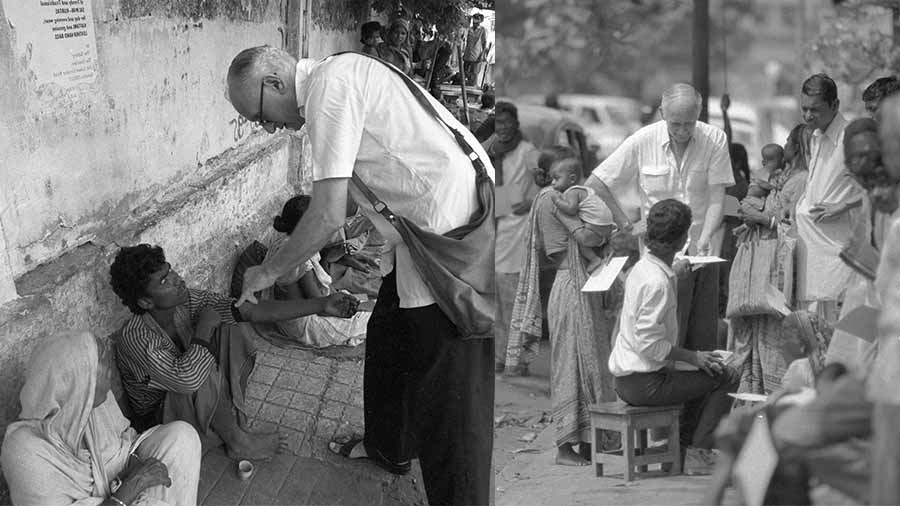

Founded by Dr Jack Preger, a travelling medicine man in the 1980s, Calcutta Rescue is a charity which describes itself as "working to improve the lives of the poorest people in and around Kolkata".

Dr Jack was known for administering medicines on the streets, and his first clinic was set up in Middleton Row. Courtesy: https://calcuttarescue.org/calcutta-rescue/

In fact, medical intervention for people like Gour Das was the original intention of Calcutta Rescue. When they were contacted to come to Das’s aid, they were quick on the uptake, whisking him away to a clinic to run tests. Counselling services were also set up in order to stem the depression and the pervading sense of fatalism which had begun to set in, triggered by poverty and pain. His wounds were dressed thrice a week for four months until it has now petered down to once a week, keeping surgery at bay. Raw food is still supplied to him regularly.

Talapark Clinic is Calcutta Rescue’s largest clinic. It saw 80 patients every day before the pandemic, but footfall has now dropped to half, in keeping with the norms of social distancing. The clinic has delivered medicines from Murshidabad to the Sundarbans and tele-consultation has replaced physical visits

Looking out for destitutes like Gour Das is what Calcutta Rescue does best. "That was the original Calcutta Rescue, we’ve always done that kind of work,” explained Jaydeep Chakraborty, CEO, Calcutta Rescue. “But we’ve evolved since then. We also have medical and education programmes."

The Rescue System

Calcutta Rescue prides itself on its research and Jaydeep believes that the key to change lies in systems and processes. They have data for 25 slums which illustrate, across 16 indicators, where the deprivations lie. There are no blanket rules; some score high on some factors but not others. For instance, nutrition is a major concern for a slum near Nimtala, while 70 per cent of the people in a Bagbazar slum are lacking in sanitation. “We used to treat each slum in the same way but now we know that the circumstances are different and we need a strategy for each of them. Improving sanitation is easier than improving nutrition. We’ll build toilets but we’ll also have to teach them how to maintain them,” said Jaydeep.

There is also a Poverty Score for each slum, which ranges between 0 and 1. A score of 1 indicates that 100 per cent of households are 100 per cent deprived on all the indicators. The closer to 1 the score is, the more deprived the slum is. “We are determined to reduce the scores,” said Jaydeep.

There is likely to be open defecation in any slum along a canal. Sanitation was a problem in this Dakshineswar slum, which is sandwiched between the Metro line near the Dakshineswar station and Belghoria Expressway. With toilets and pipes installed, ‘the Dakshineswar bustee has gone from 100 per cent open defecation to zero,’ according to Jaydeep Chakraborty, CEO, Calcutta Rescue

CALCUTTA RESCUE IN PICTURES

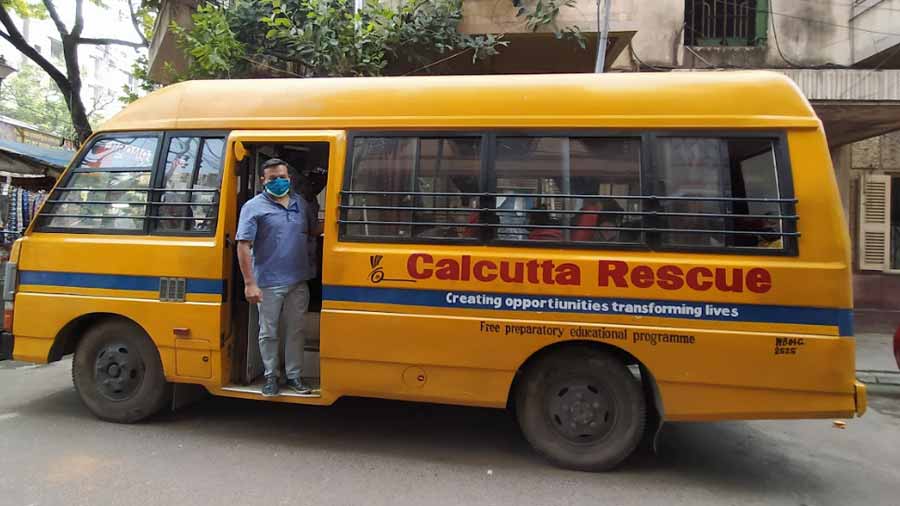

Mobile Clinics

The mobile clinics are not just a one-time health camp. They arrive week after week, month after month, offering medical assistance to ensure that health statistics actually change over time. This van is stationed near the Bagbazar canal area, where most of the patients are women and young children.

Education

When children visit one of the clinics, Calcutta Rescue tries to incorporate them into the education system. During the pandemic, the Education on Wheels programme took classes to the young students; 650 children (more girls than boys) are currently enrolled at the education centre, for tuition.

Employment

There is also a focus on handicrafts to aid employment. This is Jiauddin with his painted kettle. He is particularly skilled with his hands. Although there are 10 people working out of the centre, there are at least 20 women working from their homes.

The handicrafts are available from the e-catalogue on their website.

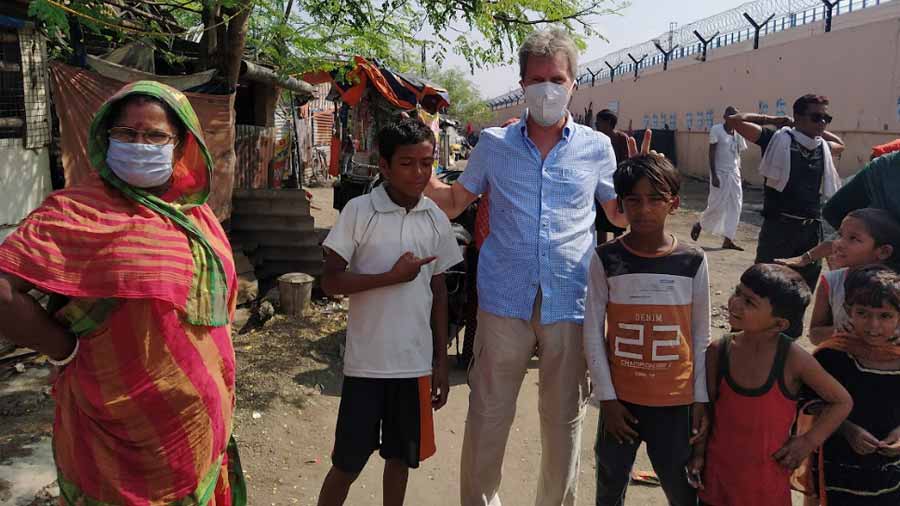

Help from around the world

Ed Thompson, one of the benefactors of Calcutta Rescue who lives in the UK, took a tour of how things are done by this charitable organisation when he was visiting the city. Here he is with the kids of the Dakshineswar slum, who are frustrated at not being able to go to school and play during the pandemic. The boys are especially fond of playing cricket and are following the matches as keenly as they can, on cell phones. Most of the slums boast a 40 per cent ownership of smartphones. Many of these were given out during the pandemic to aid online teaching.

Jaydeep Chakraborty, CEO, Calcutta Rescue

Jaydeep Chakraborty gave up a career in engineering to work in the social sector. As the only Indian kid in his school in London, he’s no stranger to what it’s like to be a bit of an outcast. On his trips to Kolkata, during holidays, he was struck by the poverty and segregation he witnessed, certain images seared into his young brain. When he grew up and started to become disillusioned with his engineering job, it was these memories of destitution and injustice that made him turn to the social sector and move to India. “My journey has brought me here, this is my zone, this is where I want to be. In fact, I was lucky enough to work with Dr Jack for almost three years,” said Jaydeep.

Meanwhile, in Jodhpur Park…

Gour Das’s wound is well on its way to healing and he is seen hobbling around the neighbourhood, where for months he could barely stir. He is provided rice and pulses so as to not be dependent on his meagre earnings. It is now the pandemic which is proving to be an impediment to his life. “Not as many people want to eat peyanji and aloor chop these days, so I don’t know if it’s worth my time to set up the stall again,” he said, ruefully.

But he is, at any rate, back on his feet. Rescued.

Read more about the work Calcutta Rescue has done on www.calcuttarescue.org.