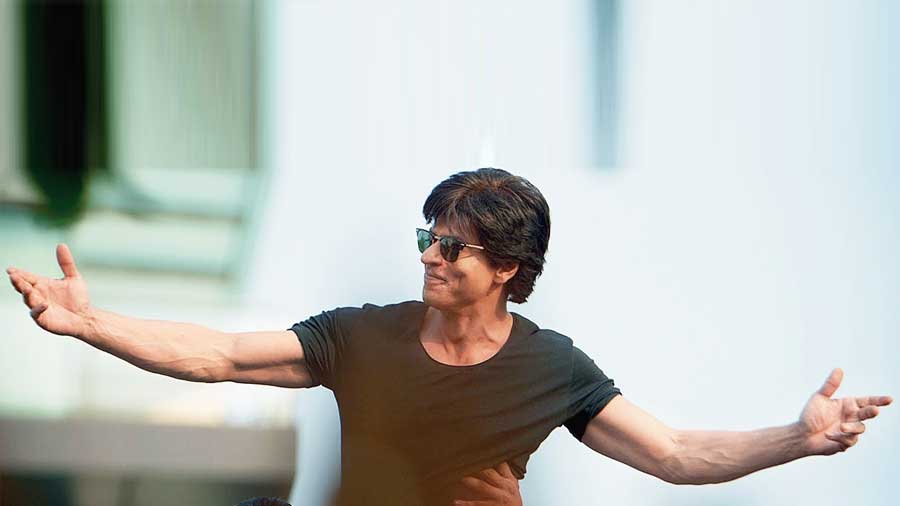

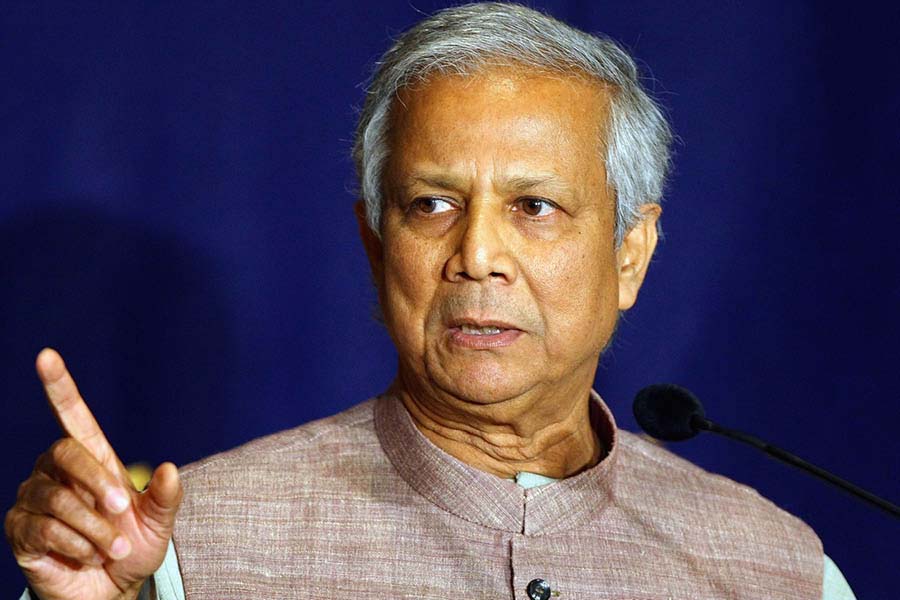

“We are committed to creating a world of three zeroes — zero net carbon emissions, zero wealth concentration and zero unemployment.” So reads the quote on the office wall of Muhammad Yunus, 83, a Bangladeshi social entrepreneur and economist who received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006. When My Kolkata met Yunus at his Dhaka office, Cyclone Remal was gathering momentum outside. But Yunus was his usual self indoors — unassuming and unflappable. One of seven people in the world to have been awarded a Nobel Peace Prize, the US Presidential Medal of Freedom and the US Congressional Gold Medal, Yunus is known as the pioneer of microfinance for his work with Grameen Bank, a microfinance specialised community development bank founded in 1983.

In January, Yunus was sentenced to six months in prison on the charges of violating labour laws at Grameen Telecom. He has also been charged with corruption, tax evasion and money laundering. For his part, Yunus denies all the accusations. He believes they are politically motivated. Last August, more than 100 Nobel laureates had signed an open letter asking for the labour law charges to be suspended.

But the conversation with Yunus begins on a lighter note, with him looking back at his childhood. Despite not being from a well-to-do family, Yunus says that he felt loved: “We were seven brothers and two sisters. We had a lot of fun, sometimes playfully fighting among ourselves. I grew fascinated with newspapers and magazines. At that time, magazines for kids would come from Kolkata. All the printing facilities were in Kolkata and I saw the city as the home for everything intellectual.”

‘We took the ship and there were a lot of passengers. We were entertaining them and singing non-stop for 15 days’

At 15, Yunus went to Canada for an international jamboree. Getty Images

Perhaps Yunus’s most interesting journey growing up was one he has narrated in his book, Boy Traveller. His association with the boy scouts introduced him to jamborees and rallies. One such jamboree took Yunus to erstwhile West Pakistan, including Karachi: “The tour was organised to introduce us to West Pakistan. We loved it! We lived on the train for two and a half weeks. We explored numerous places such as Mohenjodaro and the Khyber Pass. I had read about these places in books, but I was finally able to see them in person.”

At 15, Yunus was selected for the eighth World Jamboree in Canada. This involved him going to New York from Plymouth by ship: “We took the ship and there were a lot of passengers. We were entertaining them and singing non-stop for 15 days. For the return journey, the organisers decided to take us across Europe in three microbuses. We went to Germany and were given a guided tour of the newly restarted Volkswagen factory. We spent six months across Europe in three microbuses we bought from Volkswagen. On our way back, we also went to India and explored Agra and other places,” reflects Yunus. He wrote a book on this experience, originally in Bengali, which lay forgotten at his house, only to be published as Boy Traveller in 2020, translated into English by Muhammad Ibrahim, his brother.

When Yunus got the Fulbright Fellowship to study PhD at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, the US was going through a unique moment in history, with youngsters at the forefront of political and social change during an exciting but turbulent decade of the 1960s. For a 25-year-old, this was mind-boggling.

Watching campuses protesting against the Vietnam War from up-close filled Yunus with revolutionary zeal. As “Hell no, we won’t go” chants filled the air (regarding the opposition of sending more US troops to Vietnam), Yunus understood the currents of social change. He participated in a demonstration for integrating a small coffee shop outside the Vanderbilt campus, as one headline moment after the other engulfed the US, including the assassinations of John F Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr.

“Go find the world, discover yourself. Don’t stay all your life where you are. Challenge everything because you have the capacity to change the world. It’s young people who can change the world. Old people have old thinking, their minds contaminated with old thoughts,” believes Yunus. He adds: “Today’s youth are the most powerful generation in history because you’re born with smartphones and instant connectivity around the world.”

‘I was angry because I didn’t know how I could be useful to people’

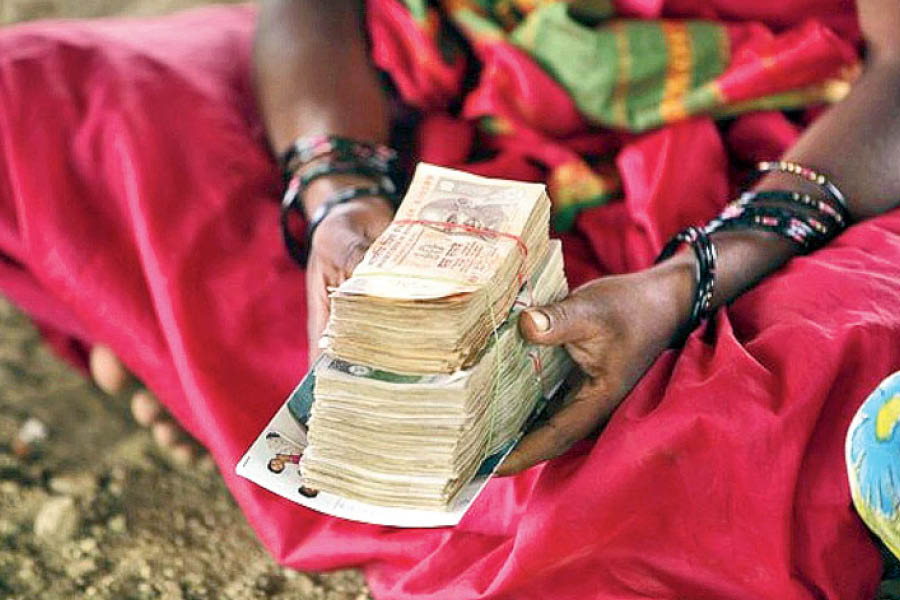

Microfinance was Yunus’s way of trying to contribute to the development of Bangladesh. TT Archives

Yunus came back home from the US in 1972, a year after Bangladesh was born. Having joined as the head of the department of economics at Chittagong University, Yunus thought to himself: “What am I supposed to teach in economics? Poverty is increasing, children are malnourished, people are dying of hunger.” Yunus pauses for a few seconds before he says: “I was angry because I didn’t know how I could be useful to people. I had a PhD and had spent so much time learning. But all my learning seemed useless.”

But a domestic crisis did not lead to personal disillusionment. Yunus decided that he was going to start by being useful to one person. He began by visiting the village near his university campus: “I became a part of the village. I realised loan-sharking (the practice of lending money at unreasonably high rates) was a big problem and saw loan sharks going after every last drop of blood, sometimes for only a couple of dollars. I tried to do something to fix this. Instead of people going to the loan sharks, I could give money to them. Gradually, I became very popular to borrow money from,” smiles Yunus.

Yunus had effectively created the roots of microfinance in Bangladesh. He then began talking to banks to lend structure and scale to his idea. However, banks, insistent on the credit worthiness of villagers, were not willing to change their ways. Yunus advised banks to begin focussing on “people worthiness” rather than “credit worthiness”. When that did not work out as planned, he proceeded to create his own system for microfinance. “I got into a battle with the banks. And I thought I should create a bank for the village and call it Grameen Bank (which translates into “Village Bank”),” says Yunus. Today, Grameen Bank has over nine million borrowers, mostly women, and has disbursed $38 billion in loans since its inception.

Reflecting on his journey in microfinance, Yunus says: “It’s the women I met in the villages who have inspired me. Because of the empowerment of women, all of Bangladesh has been transformed. Earlier, women weren’t allowed to come from the back of the house to the front. Now women are running businesses and owning their homes.”

Yunus continues, explaining the second-order effects of microfinancing, produced through Yunus Social Business, a non-profit, impact-first organisation: “It’s not just about empowering women, but also about empowering society. For example, we started selling high quality seeds to create high quality produce. Night blindness disappeared due to children eating vegetables with high content of vitamin A. Loans started being used to make toilets and homes. We put conditions based on which there were incentives to transfer the title of the land to the women in the house. The divorce rates also dropped.” So far, Yunus Social Business has provided employment, education, clean water and healthcare to nine million people across India, East Africa and Latin America.

‘Something terrible is going on in Bangladesh, and I’m under serious attack’

Yunus’s nightmare is to ‘end up in a world without problems’. Getty Images

Yunus is a strong advocate against the exclusive objective of profit maximisation in business. According to him, “Businesses should be of two types, one geared towards profits and another for solving human problems (even if it means having no intention of making profits). Ultimately every business, I hope, can become a social business by choice. I don’t recommend people that go for jobs. Jobs are slavery.” He goes on: “Everyone is born with entrepreneurial capacity. The journey of life is meant to unleash their entrepreneurial capacity they bring with them. Each person should start their own venture and make the world a better place. If you take a job, you’ll never discover yourself.”

In his ninth decade of life, Yunus still remains fervently optimistic. To him, “every problem is a world of opportunities”. His nightmare is to “end up in a world without problems”. “I’m privileged to be born in Bangladesh, in a country with a lot of problems to solve. When I wake up in the morning, I still think about what’s new and what I can do for my country and for the world.”

Reflecting on his Nobel Prize, Yunus says, “When I see my life, I see a continuously expanding seedbed of ideas. I want to make my ideas grow. Awards and prizes are a way of encouragement by friends and well-wishers, but I want to do more… There’s so much more to do.” As for his legacy, Yunus wants it to be a commitment by the youth across the world to the three zeroes — zero wealth concentration, zero unemployment and zero net carbon emissions.

With a spate of legal cases against him, Yunus admits to feeling alone and alienated: “Something terrible is going on in Bangladesh, and I’m under serious attack. The government wants to put me in prison over cooked-up charges. I have to go to court twice every month.”

As for the little leisure time Yunus gets, how does he like to spend it? “By working. When an artist has free time, they draw more. When I’m free, I enjoy working more because that’s what gives me purpose.”