Marketing communications personnel, academic and author, Bhaswati Ghosh has been a probashi Bangali for long but that has only strengthened her ties with her motherland as is more than evident in her works.

A resident of Ontario, Canada, and a Charles Wallace Trust Fellow for Translation, Ghosh channels her inner dichotomy of being an immigrant with experiences from her childhood and present life into fiction, non-fiction and poetry.

My Kolkata caught up with the writer to find out more about the person and her literary work. Excerpts from the chat follow...

My Kolkata: Tell us about your childhood. Did you always want to become an author?

Bhaswati Ghosh: Not as a child. I think, as a child, you want to pursue the kind of vocations or professions you see around yourself. Like many children, especially girls in India, growing up I wanted to be a teacher. That was the first role model that I saw in front of me. So, there were no aspirations to become a writer even up to my teenage years. That sort of came gradually as I moved out of school. Again, it was not about becoming a published writer but just to write. I wanted to write, to express myself.

In my family, when I was growing up, my brother and I lived with my maternal grandparents. My maternal grandmother was a published author in Bangla. There was this constant example — she was always writing. And, we had that atmosphere of books, because my mother worked in Delhi University’s library and she handled the Bengali books section. She used to bring a lot of books, mainly for my grandmother, but also for me because the school we studied in had Bengali as a subject. So, she would bring children’s books for me. There was an atmosphere of reading and writing within the family. I think it was probably more subconscious.

When I was in Class IX, I wrote my first short story in Bangla. It was clearly inspired by my grandmother’s activity of writing that I saw so closely. It was all around us all the time. I showed it to her and her approval meant the world to me. It must have been an affectionate nod of approval from her side. I don’t know if it was based on the merit of the story, but that kind of gave me some encouragement. So I kept on writing informally. But it gradually takes shape within you — that seed which is already there grows as it gets more nourishment. I joined some online writing communities. When you see other people working towards a book or a manuscript you also get encouraged. I also felt like telling a story in the form of a book at some point.

Meeting legendary singer Kanika Bandyopadhyay in Santiniketan for the first time at the age of 18 — how would you define the experience?

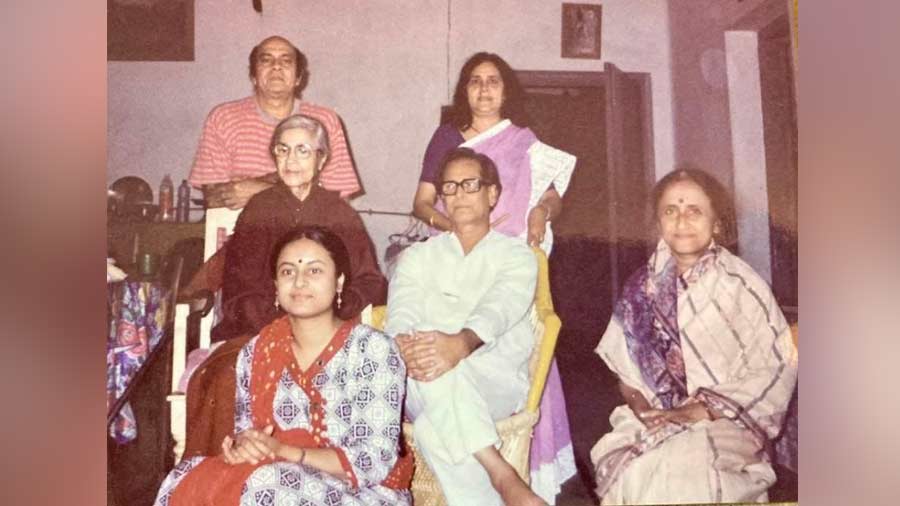

My mother studied in Santiniketan for two years. She did her master’s in Bangla there. That is our connection to the place. So whenever we visited Kolkata, my mother would always want to go to Santiniketan and whenever she visited Santiniketan, she always met Somendranath Bandyopadhyay, one of her professors (I have also translated one of his books). He was a first cousin of Kanika Bandyopadhyay and they lived just a few houses from each other. On one particular visit, he asked us whether we would like to meet her and who would say no to such an opportunity! I cannot even describe what that moment, that experience was like. To be in the presence of such a luminary person, to see the kind of humility and modesty that person had is indescribable. She met us as if she had always known us and because my mother had a connection, they instantly formed a rapport and exchanged stories. Mohordi (Kanika Bandyopadhyay) was very much a part of the ashram when my mother studied there. My mother recalled some anecdotes. They had never met before but those stories and reminiscence kind of brought that time alive for them.

Bhaswati Ghosh with legendary singer Kanika Bandyopadhay and professor Somendranath Bandyopadhyay in Santiniketan Bhaswati Ghosh/Facebook

As a Bengali in Ontario, how would you define parobash (living away from your homeland), the idea of home, and the relationship with India?

It takes a while to settle down in a new place, especially one which is so remarkably different. It is culturally different, the weather, the climate, the languages spoken — everything is entirely different. It took me quite a while to think of Ontario as home. I still don’t know if I feel rooted enough. But it is my home for all practical reasons. I believe that the way you stay connected is by keeping in touch with what’s going on in your home country and at the same time finding new connections in your new environment.

The idea of home is not a place. I think it’s more of a sensibility. We visited Mexico City in 2017 and I felt like I was back home suddenly. Because the trees, the birds, the entire landscape, the profusion of colours of houses, all reminded me of India. Since it's a tropical country, the flora, the fruits and the vegetables are similar. Just the profusion of colours was so different from the very uniform greys and monotones that you see in the West that it immediately took me back home in spite of the fact that I was so far away. I realised that a home is not essentially a place but a bunch of memories stuck in your head and associations that you make with different things — music, colour, food. So, whenever you find some traces of that, you feel like a part of your home is at that spot. I would say, it’s probably a mix of nostalgia, memory, sensory delights and experiences. That’s what home is.

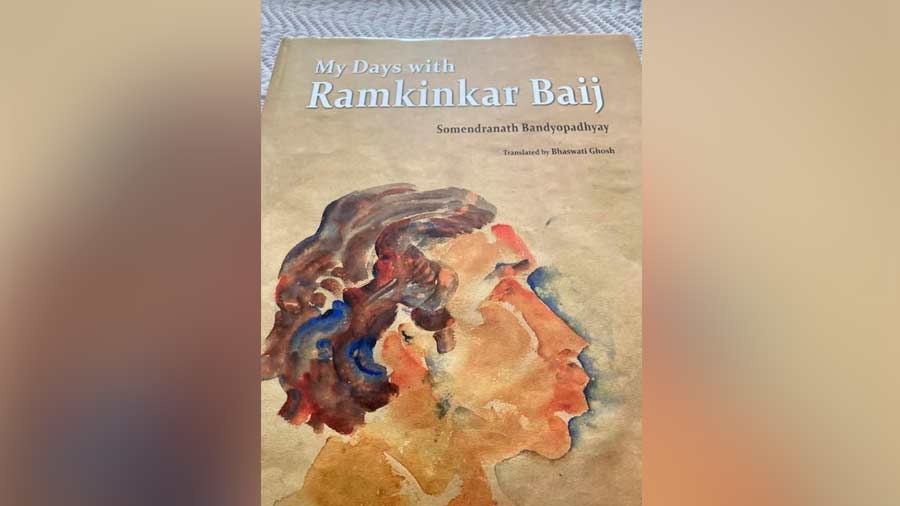

You received the Charles Wallace Trust Fellowship for Translation for My Days with Ramkinkar Baij. How was the journey while translating the book and spending time at the British Centre for Literary Translation at the University of East Anglia? Why did you choose this book for translation?

I spent about a couple of months at the British Centre for Literary Translation and it was an amazing experience. It was my first journey outside India. I was quite intimidated at first because I had no experience of travelling alone and staying alone in a place. I had always stayed with my family before that. In India, as you know, we are very sheltered and protected. It was sort of challenging in the beginning, just mentally, not the actual aspect of travelling. It was an extremely liberating experience, as it turned out, because you had to learn a lot of life lessons besides the actual translation part which was the project that I went for. The solitary experience brought in a lot of individual growth. And the perfect atmosphere was just. Norwich had a very beautiful landscape and I think it was just the right atmosphere to focus on work. I had already done some parts of it, but I could take it through to completion while I was there.

We got to interact with students who were studying translation. There was a cross-pollination of ideas. They were translating from various different languages. When we had our discussions with them, my fellow translator and I, we got to hear from them the kind of challenges they encountered, for instance. That was quite educational, I would say, for me in many ways. We had access to the libraries which again gave us a lot of room to grow and learn. The professors there were also very helpful.

To answer why I chose this particular work, this particular work sort of came to me unannounced and unexpectedly. The book is written by professor Somendranath Bandyopadhyay. On the same visit that we met Mohordi, he gave a copy to my mother and on returning to Delhi my mother read the book and was quite fascinated. She had seen Ramkinkar Baij at work when she was at the university. So, she had very vivid memories of him doing his work. He had a very lively presence on the campus. She could relate to a lot of what was written in the book. She kind of kept impressing upon me that I should also read the book. I began reading the book and from the first sentence I was mesmerised. It began with a description of Ramkimkar’s living quarters, what kind of person he was. The book is written with so much affection and deep respect, too. It is also very literary and the style completely intrigued me. I just wanted to share a bit of it, not the book but probably the parts that drew me the most. I translated excerpts from a couple of chapters and shared them on my blog and that’s how it began. Then when there was a call for the fellowship, my brother who had read those parts encouraged me to apply for this particular book. By the time the translation was completed and it took the form of a book, the author had also come to know that someone had posted excerpts of his book on a blog. He did not know it was me because he knew me by my pet name. So that’s why I said it all kind of happened accidentally.

A copy of ‘Silipi Ramkinkar : Alapchari’ by Somendranath Bandyopadhyay translated by Bhaswati Ghosh

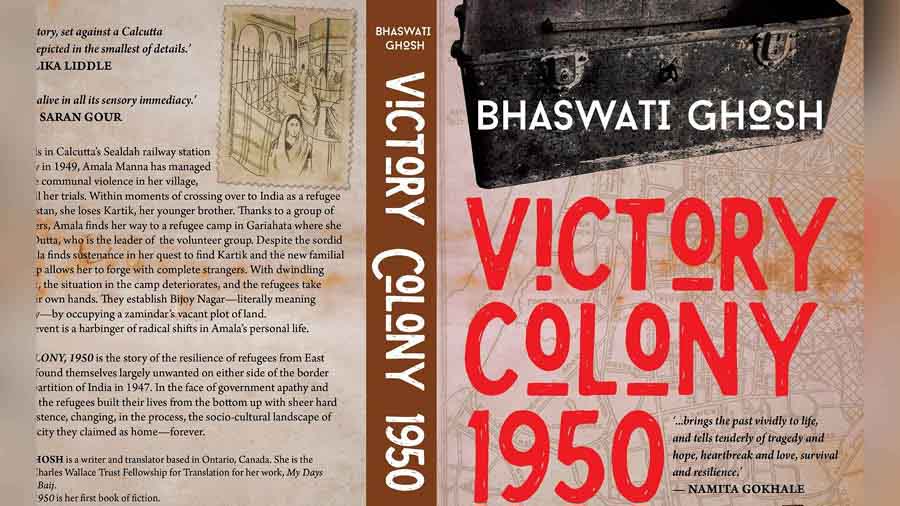

Could you walk us through your journey while conceptualising and writing Victory Colony, 1950 in 2020.

The concept came through family narratives because my grandparents were from Barishal in East Pakistan (now in Bangladesh) at the time of the Partition. Since my grandmother was a writer, a lot of her stories after Independence were based on that aspect. She wrote a lot of short stories and many of them dealt with the theme of Partition because it was very raw for them and they had lost all their property. Fortunately enough, at least I don’t know of any life lost in our family due to Partition. But I know the loss of property was a lasting scar that stayed with my grandmother. My grandfather did not speak much about any of this, he was a quieter person. But my grandmother told us stories of her childhood and they were very happy stories.

Later, when I started reading her stories, I saw that they bore a very different kind of reality. They were not really about that nostalgic past but about the horrors of Partition. My grandfather was working in (then) Calcutta even before Independence. So the transition wasn’t so difficult for them. They had family in Calcutta. And when they had to move to Delhi, it was something of a shock because they did not have any connections in Delhi at all. I came across some stories about the poorest of the poor and how Partition affected them. And I was so shocked because these were stories my grandmother never shared with us. It was a sort of reality check and I was particularly moved by a story of a brother and a sister whose lives end in absolute tragedy. So that kind of stuck with me and I wanted to reimagine their future once they had moved to India. I wanted to see if there could be another alternative to how their story developed. That was the seed of Victory Colony 1945 — it was about these two siblings who had lost everything and who have had to cross over and don’t know what to do now with their lives and how to survive day to day.

The book 'Victory Colony 1950' deals with themes of Partition and in inspired by narratives from the author's own family

Your blog offers a very interesting read. The section titled Immigrant’s Postcard especially draws attention. Do you consider yourself an immigrant? How would you describe the sense of displacement or the continual search for home?

Yes, I am an immigrant. As there are many communities in Canada, it is a country of immigrants. Their own population isn’t sufficient to fulfil the requirements of the country, so they invite and welcome immigrants. And that’s why it’s a haven for people of different communities. I am definitely one of them from the Indian subcontinent.

I think the search for home is really intense. I wrote the series Immigrant’s Postcard in the year of my coming to Canada. If you look at the timeline, you can also probably trace the search. Because, the search is so intense when you are new and the pull of your home country is so strong at that time that everything in the new place reminds you of or makes you want more of your home country. It is a very strange phenomenon, but I think it affects most immigrants when they move.

Recently, we met my husband’s friend’s son who is here to study and he comes from a remote place in Punjab. It’s not a very well developed place and so there are very few opportunities. He told us that he misses that particular place, his home, so badly. He said, you know, all the amenities are here and the living standards are much higher, and I never thought I would miss that place. That is how strong the bond is to your place of origin.

So I think when you are new as an immigrant that feeling is very intense. But as you spend more time in your new environment, I think something of that also seeps into you and you begin to appreciate some of the aspects of your new environment. There is a pause that comes in the search, there is more of an acceptance of your reality that you are placed in a different environment, which is also home. But your ties with your original home are not severed but there is an acceptance that both that and this are now home, and you are not really on a quest to find home so badly any longer, which is good for at least your mental peace.

At the same time, you can make a home in your heart with a lot of things. It doesn’t have to be a specific geography. Like, I am very strongly connected to news from India. I stay abreast — I probably know more about India than Canada even now. Especially when I write stories of fiction, I think only one story that I wrote was based in Canada. But all my characters, all my stories are always set in the sub continent. I think that in some way that establishes my relationship. The interesting thing is that the poems that I write, the non fiction essays, the personal essays that I write — they often talk about this experience. So the only conclusion I could draw is that this is my reality, I am an immigrant but in my imagination I still remain an Indian. My fiction writing is based on that region and the happenings there and my sensibilities, but my non fiction writing and poetry speaks more of my current experience as a diaspora person, as an immigrant.

Your blog says you are writing a book on Delhi. Tell us something about that.

This is a non-fiction book. And it began with my own story of growing up in Delhi as a Bengali. I wanted to share that experience of what it was like to grow up as a Bengali in Delhi, which is a melting pot of so many different communities. But, the idea was taken to the publisher — because for non-fiction books you don’t have to have a manuscript to find a publisher, you only need to have what is called a concept note or a proposal. So when I pitched my proposal they felt that with just my own experience of being a Bengali in Delhi, the focus would be too narrow. It would only appeal to Bengalis living in Delhi. They (the publishers) wanted me to broaden the scope and include other communities. So that is what the book is about. It is about the different communities who came to Delhi and settled down and made Delhi their home. It is about that aspect of how different communities have shaped the history and the growth of Delhi and continue to do so. Certain decades have particular communities coming and they completely change the character of the city. Because every community brings with it its own culture, traditions, which as an immigrant I know we want to preserve when you are in a new place. So that also has an impact on the overall cultural landscape of the city. That is the story that I am trying to tell. The book is probably a peoples’ history of Delhi. Its main thrust is oral anecdotes and it will also have some aspects of actual history and the development and growth of Delhi after Independence but probably also touch upon the period before Independence too.

When is the book coming out?

As soon as I finish it (laughs). I have written most of it. The biggest challenge for this book was the pandemic. Not only could you not travel, which is very important for a book of this nature, but I could also not interview anybody even on phone because the atmosphere was so different. So that kind of set me back a bit and I am pulling it up again, trying to get it to finish.

The author-translator at work Bhaswati Ghosh/Facebook

Who are your favourite authors, and which are your most favourite or go-to books?

I think I have only one go-to book or maybe two. Both are by Rabindranath (Tagore). One is Lipika and the other is Chinnopotraboli. His book of letters (Chinnopotraboli) appeals to me a lot because it describes the natural beauty of rural Bengal in such vividness but also brings me closer to Tagore as a young, vulnerable writer. In the letters he expresses his vulnerability, he expresses self doubt. Since these are of personal nature, he feels free, probably more liberated to do so. And that attracts me a lot because you can relate to so many of those as a writer and someone who is also trying to practise the same craft. And it shows you, you know, like I said for Kanika Bandyopadhyay, that even though they have this aura and persona and you have always followed them as icons, they can show a very human side. In these letters of Tagore I see that very human side, very vulnerable side.

My favourite writers keep changing. There have been so many regional writers from India who have inspired me. The kind of stories they write are so rooted in culture, environment and in the local — that is something I want to imbibe in my writing.

Tell us about your grandmother Amiya Sen and the short story collection by her — Punorbason o Onyanyo Kahini.

When my grandmother was alive, all these short stories were published in different publications in journals of that time. But they were not collected as a book. While my grandmother was alive, she published two books. One of them was Aranya Lipi — a non-fiction account of the refugee resettlement plan taken up in Dandakaranya by the government of India in the 1960s. My grandmother had travelled there, sort of under cover, spoken to the refugees and written about the ground realities, because all the government stories were very positive but the reality was very different. She went there in the guise of a Bengali teacher, which they needed, and she did teach the refugee girls but her main purpose was to gather information and bring it out. The other book was called Shonai Shono Roopokotha, a book for children about the Freedom struggle. But the title says roopkotha or fairy tale because that is how it would sound to modern-day children, if you told them those stories. There was another small book of non-fiction that she wrote about Delhi, very similar to what I am trying to write now. It is called New Dilli’r Nepothye. It is about the different kinds of colonies that came up in New Delhi after Independence and the naming convention. Those were the three books she published during her lifetime. But there was this collection of short stories that was lying all scattered and published in different journals. She had a strong wish to see this come together as a book, and it did not happen during her lifetime. She always used to say for whatever reason that I will publish this book when I grow up. It was a sort of responsibility and bit of guilt that I carried that I could not do it. I finally managed to get all these stories, and my mother was a huge help. She transcribed all the stories; some of the ink was fading in the old copies of my grandmother’s writings. She passed them on to me and I could work with a publisher to give it the shape of a book. Many of the stories are about the resettlement of the refugees and that’s why one of the stories is called Punorbason.

Will there be a collection of poems by you in the future?

I am an amateur when it comes to writing poetry. It was not one of the most instinctive things that I did as a writer. Because I think my biggest strength is writing non-fiction. That comes the most easily to me and it’s something I enjoy doing. I feel that I am primarily a non-fiction writer who happens to write fiction as well. I began to write poems very gingerly, in a very unsure way. I was always scared or self- conscious about it. But as time went on, I found another potent medium of expression and I joined a group of poets and that kind of gave me a thrust because it forces you to write every day and share it with the community. That kind of encouraged me to do a bit more and that's how more poems got written. But, I have not thought of a book. I just want to become better at writing poetry and developing the craft.

The two books Bhaswati Ghosh keeps revisiting are Tagore's 'Lipika' and 'Chinnopotraboli' Bhaswati Ghosh/ Facebook

What are your upcoming plans?

I am not working actively on any other book. The only other book that I am working on is a translation of Aranya Lipi, my grandmother’s non-fiction book. I have done a few chapters of it and I would like to finish it because, I feel, it is a very important insight and refugee stories are not something that are only situated in a particular time. That is a kind of crisis that continues into the modern day in different parts of the world. So I think there are a lot of insights to be gained from a work like that. Other than that, I have a vague plot for another novel, it’s only in my head that I have a story forming. But, I have not had the time to really think about it. I want to finish my work in progress first. I have a full-time day job and that gives me only that much time for my creative pursuits.