Quantity over quality has long characterised India, not least when it comes to laws. With the world’s longest written Constitution and more than 1,200 laws, it is no exaggeration to say that Indians love to make laws, if not always follow them. But not every problem in society deserves a law. And sometimes a law in itself can create a problem.

Few people in India understand this as well as Arghya Sengupta, founder and research director of Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, which has acquired a pivotal role in India’s legal landscape since launching in December 2013. In the decade that it has been in operation — with offices in Delhi, Mumbai and Bengaluru — Vidhi has championed a rigorous, research-oriented approach to crafting and understanding legislation with the goal of creating a society where “better laws lead to better governance”.

Original research, engagement, and shaping the public narrative

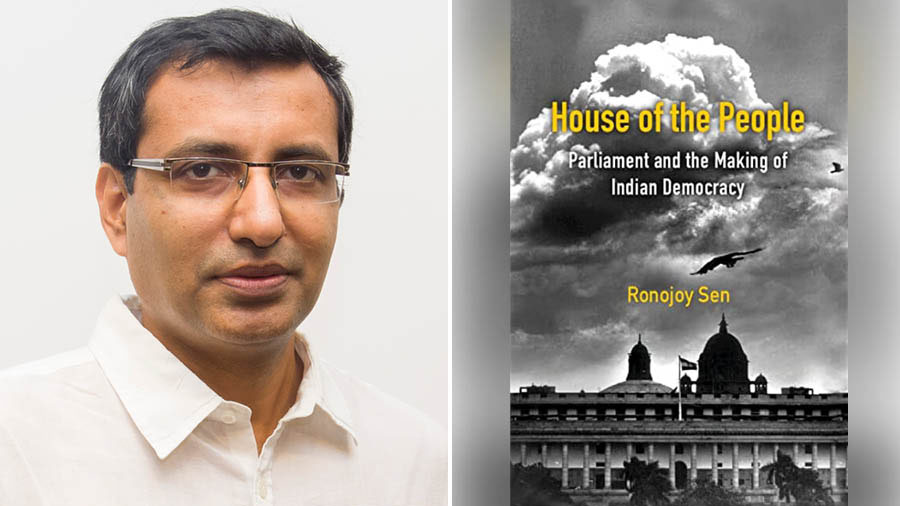

Arghya Sengupta was a lecturer in law at the University of Oxford before setting up Vidhi Arghya Sengupta

“Vidhi began because we wanted to write better laws for India. Legislations and policies were getting complicated and didn’t cater to what we call the 5Cs — laws were not constitutional, not clear, not compliant with international law, not coherent with other laws that exist [in India], and not contemporaneous with best practices,” says Sengupta, 39, born and brought up in Kolkata and currently based in Delhi.

According to Sengupta, there are three ways to write better laws, which also offer a neat glimpse into Vidhi’s scope of work: “The first is original research. For instance, in-depth research done by us shows that drug addiction isn’t a criminal justice problem but a public health issue. So, public money needs to be spent on de-addiction rather than on imprisoning certain drug offenders. The second is engagement. Regardless of political affiliation, central and state governments are the biggest agents of change. Which is why we assist them in the drafting of legislation on a variety of issues. The third is shaping the public narrative, particularly in areas where there’s a lack of political impetus. We do this by filing cases or undertaking public campaigns, as we did in the case of leprosy, leading to the removal of 20-odd statutes over six years that discriminated against persons with leprosy.”

Having started his career as lecturer in law at the University of Oxford, Sengupta’s idea for Vidhi took shape during 2009-10 in relation to the Indo-US nuclear liability bill (which formally became The Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act, 2010). At the time, Sengupta and his “group of fellow graduates” had submitted an unsolicited report to the standing committee of Parliament in an attempt to help eliminate “shocking provisions in the bill that had come about through accident rather than design”. This included “capping the total amount of compensation that can be paid in case of a nuclear accident”. Many of Sengupta and his group’s suggestions were accepted by the standing committee as well as the government and became a part of the law of the land.

Gradually, Sengupta, with his Oxford lectureship acting as a catalyst for important meetings with stakeholders, formed a core team and set up Vidhi with its head office in Delhi. Besides Sengupta, the founding team comprised Alok Prasanna, the Karnataka lead; Debanshu Mukherjee, the lead for corporate law and financial regulation; and Dhvani Mehta, the lead for health. Currently, Vidhi has an overall organisational strength of 85, with the bulk of its members working out of the capital. At the time of writing, Vidhi had assisted governments across India in 396 engagements and done 369 pieces of original research besides having its fellows author hundreds of op-eds, journal articles and in-depth reports.

‘We want good research to improve lives’

Independence, excellence and impact are the three overarching values governing Vidhi’s work Arghya Sengupta

Vidhi’s productivity stems not only from recruiting “the best minds coming out of law schools in India” but is a natural extension of its core values — “independence, which involves non-partisan research devoid of any agendas, political or otherwise; excellence, which involves meeting high-quality benchmarks through academic rigour; and impact, which involves translating research into real-world change”. Additionally, Sengupta also mentions the importance of “trust, accountability, mentorship, expertise, collaboration and passion for innovation”, qualities that build an ecosystem where asking the “why question” is constantly encouraged. “We don’t want good research to be tucked away in a journal read by five scholars and commented upon by two in some international conference in Hawaii. We want good research to improve lives,” explains Sengupta.

Over the years, Vidhi has been instrumental in shaping numerous legislations in India across sectors and domains. Among these, there are three that have made Sengupta and his team particularly proud. Co-founder Mukherjee initiating the bankruptcy law reform process in India and advising the government on the designing, drafting and implementation of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016. Sengupta and his team supporting the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) in drafting the Aadhaar Act, 2016, which made UIDAI a statutory body and was a crucial step for “privacy legislation and for a free, fair and responsible digital economy”. And co-founders Mehta and Prasanna successfully intervening in a Supreme Court case on advanced medical directives, with the aim of introducing a holistic end of life care act, which allows “dignity of death to patients [often kept on ventilators in hospitals at great financial cost] while removing legal quandaries for doctors”.

‘Some people don’t understand the concept of non-partisanship’

Vidhi does not take up any projects commissioned by the private sector, working only with governments and public institutions Arghya Sengupta

Despite its outstanding and, in certain cases, pioneering work, Vidhi has often been perceived as a handmaiden for the central government, as a sort of government agency that wields too much influence. Sengupta believes that such perceptions exist because “some people don’t understand the concept of non-partisanship”, even as he acknowledges that the narrative of Vidhi being curiously close to the powers that be has watered down in recent times.

“We have worked and will work with any government that’s interested in making lives better for Indians. Moreover, we’re an independent organisation whose job is to suggest. The decision to implement the laws remains with the government,” says Sengupta, who emphasises that “getting a law through is a Gargantuan task”. Why? Because it has to first go through “the bureaucrats, then the committee(s), then the respective minister, then the law ministry, then the Cabinet, and then, at last, the law can enter Parliament”. In other words, it is not possible for any organisation, let alone an independent think tank, to become a shadow legislature on certain aspects of policymaking.

In order to retain its autonomy, Vidhi does not take up any projects commissioned by the private sector, working only with governments and public institutions by contributing original research. Funding for Vidhi comes through grants, with its patrons such as Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies, the Pirojsha Godrej Foundation, the Lal Family Foundation, and more listed on its website. “When we started, we made a conscious decision to not accept foreign funding, since we want the vision of fostering better laws and governance in India to be supported by fellow Indians,” says Sengupta. Vidhi also generates revenue through legislative consultations and collaborations with various state and central governments, ministries and courts across the country.

Opening a Kolkata office and Sengupta’s take on the Constitution

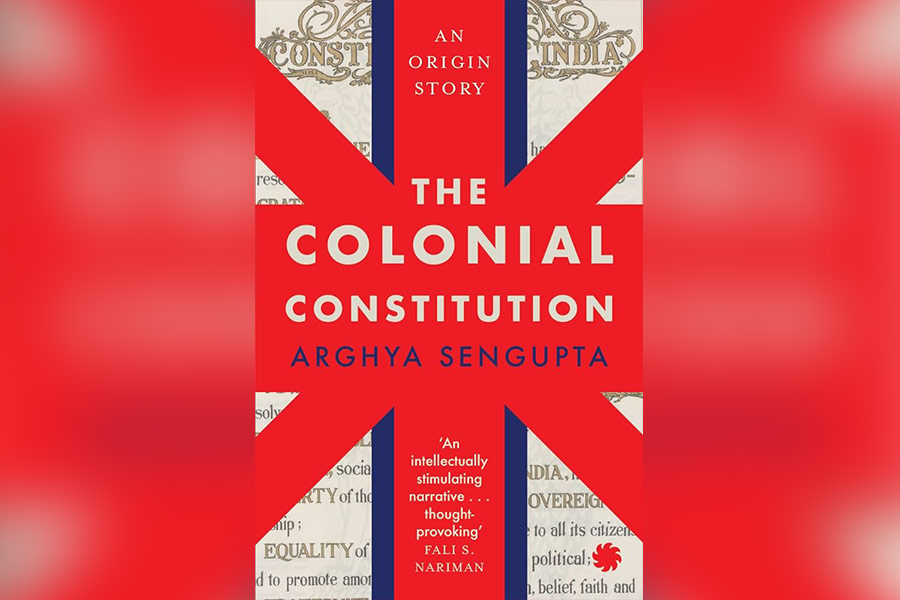

‘The Colonial Constitution’ by Sengupta argues that the Indian State towers over its citizens

Going forward, Sengupta wants Vidhi to work with more state governments (it currently works with nine) and get “closer to the people”. As part of this, Sengutpa wishes to set up an office in Kolkata at “some point over the next decade”.

When it comes to the larger picture of India as a democracy, Sengupta, as he has argued in his latest book, The Colonial Constitution, feels that “too much centralisation is a problem”. “The Constitution has set up a State that towers over the citizens… It also perpetuates colonial institutions such as an authoritarian police force [from the British era] without adequate retraining. This isn’t to say that the Constitution doesn’t have good parts such as concepts like fundamental rights and equality… I hope my book provokes people to think more deeply about the Constitution,” observes Sengupta.

Based on the feedback he has received about his book, Sengupta is confident that India continues to be a “free, liberal and inclusive society, where people are open to different points of view”. He also thinks that India is a place where passion and purpose eventually unite to create change. Reflecting on his own unconventional trajectory, Sengupta says that “in keeping with the generalisation of most middle-class Bengalis, I wasn’t a risk-taker; but beyond a point, I was certain of what I wanted to do”. And where did this certainty come from? In a nod to his Kolkata roots, Sengupta paraphrases Swami Vivekananda and replies: “It came from within, from belief in oneself.”

It is this same sense of belief that underpins Vidhi, as it marches into its second decade of helping India shift its legal focus from quantity to quality.